Commentary

Ramon Mantovani responds to Massimo D’Alema’s claims about Ocalan in Italy

‘I am obliged, out of respect for President Ocalan and the Kurdish people, to clarify some points regarding D'Alema’s claims.’

I am very happy – and I do mean it – that Massimo D'Alema wants to cast himself as a friend of the Kurdish people and to try to absolve himself of the responsibility he had in the affair that led to the illegal abduction of President Abdullah Ocalan. It means that, in spite of everything, the course of events and Ocalan's political stature have induced him to say what he said in his interview with Chiara Cruciati in the Feb. 14, 2025 edition of il manifesto.

However, I am obliged, out of respect for President Ocalan and the Kurdish people, to clarify some points regarding D'Alema’s claims.

I have repeatedly said – including recently to a Kurdish news agency – that the Communist Refoundation party, through yours truly, was asked to help President Ocalan come to our country as his life was in danger in Russia, where Yeltsin's internally divided intelligence services could have handed him over to Turkey at any moment. In order to do so, we did not hesitate to use all of our ability to call on connections inside and outside Italy and to maintain secrecy and confidentiality about all our contacts, as anyone who knows how such things work can easily imagine.

We wanted our help, and my personal involvement, to be and remain confidential – both because, unlike others, it has never been our approach to use the struggles and dramas of other peoples and movements for “visibility,” and in order to prevent the highly provincial Italian press from exploiting our involvement for miserable internal polemics that would have been detrimental to the Kurdish cause. In other words, we were not the ones who came up with the idea of “bringing” Ocalan to Italy to annoy the government or for other crackpot domestic political goals (as all the newspapers and TV stations wrote and said). As if the leader of a people of thirty-plus million would be “brought” by yours truly like he was a package being delivered.

Quite the opposite: I took care to explain to Ocalan clearly that among the European NATO countries, Italy had always been the most subservient and obedient to U.S. orders. But President Ocalan insisted on coming to Italy, basically for two reasons. One year earlier, the Italian Parliament had passed a resolution I proposed and became the only European parliament to recognize the existence of an armed conflict in Turkey and to commit the Italian government to work for a negotiated and peaceful solution.

The first effect of the resolution was that thousands Kurdish citizens with Turkish passports were granted refugee status from that point on. Interior Minister Napolitano, responding to questions in the Chamber from right-wingers, said that this needed to be done following a decision of the Foreign Affairs Committee.

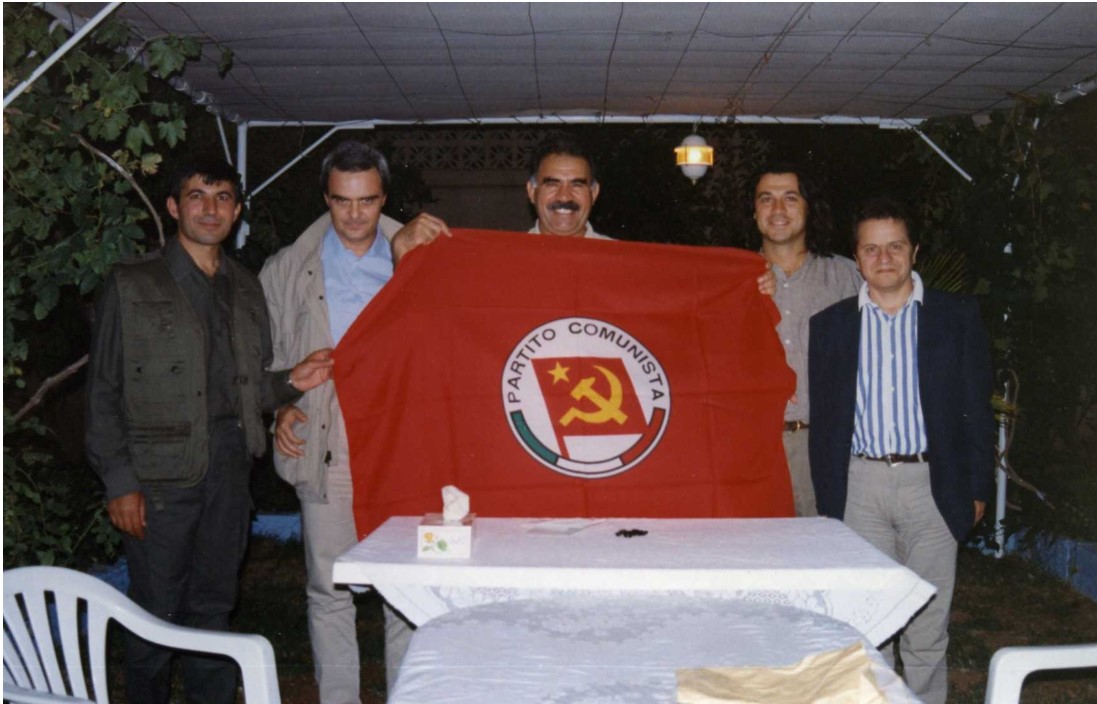

The second effect was an invitation from Ocalan to meet with him in Syria, where Alfio Nicotra, Walter De Cesarias and myself would go. Liberazione reported on the meeting, including with photographs. Ocalan was convinced that Italy, because of these events and also because it was a NATO country and the seat of the Vatican, was the best place to proclaim a unilateral ceasefire by the PKK and to propose the start of negotiations to Turkey.

These (and nothing else) were the reasons that made President Ocalan choose Italy, to try to turn a difficulty into an opportunity. These (and nothing else) were the reasons that induced us to do all we could to help the PKK and Ocalan, both out of internationalist solidarity, which was and is an inalienable principle of our party, and to get our country, if possible, to take steps to contribute to the peaceful resolution of a conflict that began with the fascist coup of the Turkish army in the early 1980s.

What D'Alema says about Ocalan's arrest is only partly true. I myself told Ocalan, upon arriving at Fiumicino, to go to the diplomatic passport lane, declare his true identity, hand over the fake passport he had with him and ask for political asylum. Sometime later, I found out that the state police’s report to the judiciary said that Ocalan had attempted to cross the border with a fake passport and had been taken into custody after being recognized.

I learned this for a fact when I myself was put under investigation as a suspect in the crime of aiding and abetting illegal entry. I had to confirm the rumors of my participation in the matter, which were certainly circulated by the intelligence services, first in Greece and then in Italy.

I also knew from an Alleanza Nazionale deputy that Berlusconi himself was preparing to spread the news about myself helping Ocalan at a press conference. What I’m saying is so indisputably true that, in fact, the magistrate who was questioning me ended his interrogation right after I explained that he could verify what I was saying about Ocalan heading to the diplomatic passport lane – rather bizarre behavior for someone who wanted to enter the country illegally – since there were numerous cameras that must have recorded the event.

The truth is that Ocalan was expected by a swarm of agents who in effect arrested him, after hearing his request for asylum, and led him out of the customs hall together with his secretary and the Italian spokesman of the Kurdistan Information Office, who acted as an interpreter. The magistrate interrogating me ended our conversation by telling me that the airport’s security camera recordings for that day and hour had vanished. This is why the charge against me was dismissed.

Well, there are two possibilities: either D'Alema, or whichever underling was acting on his behalf, forgot that he ordered the state police to file a false report on Ocalan's arrest, or this was done without his knowledge, independently, by state apparatuses that were either rogue or in the service of another country. In either case, these are very serious matters that should have been followed up by the judiciary. Moreover, I seem to recall that Umberto Ranieri, the then-foreign affairs officer of the Democrats of the Left (DS), wrote a few years later that the government had been informed and had made a serious blunder in accepting Ocalan coming to Italy. But perhaps my memory is faulty.

As for the pressures, to my knowledge, they came from many quarters. It’s certainly true that the U.S. was the most active, as D'Alema says. But aside from the confidential phone calls that D'Alema mentions, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright publicly said that Italy had to extradite Ocalan to Turkey, meaning that in addition to meddling in a matter involving two (at least formally) sovereign states, she was ordering the Italian government to violate a law of the Republic, which explicitly forbids extraditing anyone to a country that could sentence him to death.

No one in the Italian government responded properly to Albright, with a statement that would safeguard our sovereignty and also our dignity as a country. Companies from the Italian war industry, public and private, exerted their pressure as well. And it is my understanding that even high state officials did things aimed at influencing the government.

One can also easily verify, by consulting the archives of Italian news agencies, that on a certain day, in the morning, the Prime Minister and the Justice Minister claimed that it wasn’t within the government’s competency whether or not to grant asylum (unlike what D'Alema says in the interview; instead, he recounts that he had consulted the Asylum Commission), while on the same day, in the afternoon, as many as three ministers, and not just any ministers – none other than Dini, the Foreign Minister, Scognamiglio, the Defense Minister, and Fassino, the Foreign Trade minister – said that the government SHOULD NOT GRANT ASYLUM, partly contradicting D'Alema and Diliberto. It’s strange that the Italian press – composed in part of an army of tea leaf readers, gossipers, foreign policy dilettantes and diggers after small and big scoops – failed to notice this small inconsistency.

Finally, I can’t say anything about what happened after Ocalan's departure from Italy, except that in the end, after his illegal abduction in Kenya, three Greek ministers had to resign, starting with the Foreign Minister.

But I can bring my own testimony to bear, of the time before his departure when Ocalan was considering what to do, also based on what he had been advised by the lawyers Pisapia and Saraceni (who were also in the Chamber of Deputies), who, to my knowledge – contrary to what D'Alema says – had advised him to stay in Italy, since the charges brought against him in the extradition request were political scenarios rather than substantiated charges, and he would have passed the test of any Italian court that took them up.

It is also true that according to a treaty between Italy and Turkey that predated the military coup and was never annulled, right after the official refusal of extradition, any Italian magistrate could have arrested Ocalan and put him on trial on the charges of the Turkish judiciary.

I will testify that Ocalan told me that if they arrested him in Italy according to the abovementioned treaty, even though he did not fear a trial, he thought that the Kurdish people would experience his arrest in Italy as a defeat that could provoke desperate and out-of-control reactions. I, of course, limited myself to describing what would happen if he stayed, agreeing with the lawyers' opinion and reassuring him about the growth of the solidarity movement with the Kurdish people. I did not deem myself fit to give him advice, much less directions on what to do.

A few hours after I spoke with him, prominent PKK figures came to me and told me, given the brotherly relationship we had with them, that the movement thought that their president should stay in Italy, but that, of course, he would have the final say on what to do. Only at that point did I tell them, on behalf of my party, that we also thought the same and that if this might help, they could use this information to convince Ocalan to stay. I’m saying all this to testify to the human and political stature of Ocalan, who thought of his people before himself. Which is more or less the opposite of what European rulers do, and Italian ones in particular.

Abdullah Ocalan is the Nelson Mandela of the Kurdish people (and one wonders how someone would have gone down in history if they had refused to grant asylum to Mandela, the leader of the ANC’s military wing?). His writings in prison are a body of work that all of the world’s left should study, and are the grounds for the fact that Rojava is the only place in the Middle East where there is democracy, where women have the same rights as men, and where people of different ethnicities and religions coexist peacefully. However, it is still the target of constant bombings and attacks by Turkey (with weapons supplied by the Italian war industry) and ISIS.

We will always fight for the liberation of Abdullah Ocalan, whom we also consider one of our political and theoretical guiding lights.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/ocalan-ramon-mantovani-risponde-a-massimo-dalema on 2025-02-15