Commentary

Why the latest hardline drug proposal in Italy is the wrong approach

If we free ourselves from the obsession with punishment, it might be possible to reorient both human resources and economic resources toward fighting other criminal threats that are much more alarming.

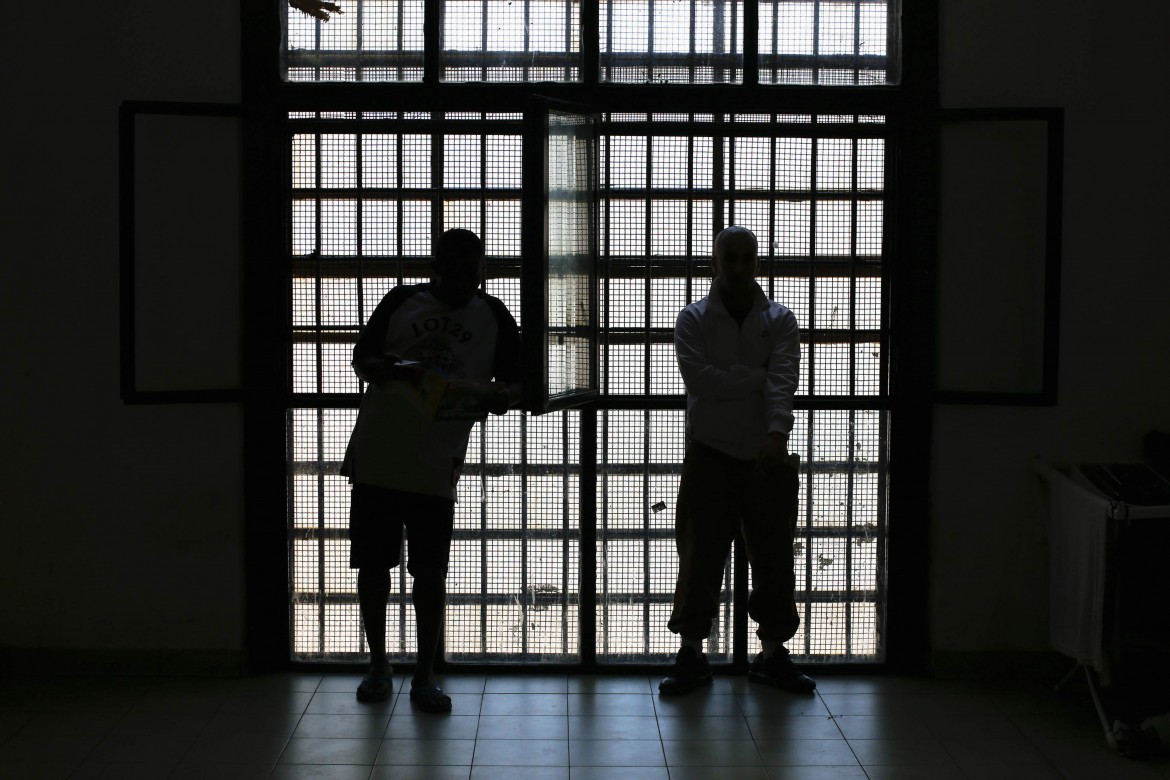

Drug addicts account for a quarter of the prison population, and those jailed for violating drug laws make up around a third of the 61,000 inmates in Italian prisons.

Those in pre-trial detention for drug offenses also make up more or less a third of the total number of detainees in our country. Furthermore, there is a subset of inmates who have violated narcotics laws and who have addiction problems at the same time. It’s not rare that the drug dealer is also a substance abuser. Quite often, these are young people who come from marginal backgrounds and who also have psychological problems.

Among the member countries of the Council of Europe, Italy has one of the highest numbers of final convictions for drug offences: about 12% higher than Spain and France and more than 20% higher than Germany.

These numbers highlight the repressive impact of our legislation (which, one must not forget, bears the names of Gianfranco Fini and Carlo Giovanardi), which is already very severe and does not need to slide any further down the securitarian slope.

Therefore, we are unable to agree with the concerns and proposals of the Minister of the Interior, Luciana Lamorgese, who announced she has prepared new regulations that go beyond the current provisions of Article 73, paragraph five of the anti-drug law and call for immediate preventive arrest in all cases of drug trafficking, even if the quantities are very small. We don’t yet know what juridical solution will be adopted to send the dealers of even minute amounts of drugs to jail.

Whatever it is, it surely cannot involve the introduction of automatic rules in the imposition of pre-trial detention, as these have already been struck down as illegitimate by the Constitutional Court on more than one occasion. We don’t even know whether any distinctions will be made between the judicial treatment of those who deal cannabis and those who deal hard drugs.

Anyone who has been working on these issues for decades is well aware that the threat of prison and the policing-focused response is a policy of anti-crime repression that has failed to produce significant results across both time and space—both in terms of combating drug dealing, reducing youth consumption (an issue particularly highlighted by the Minister in her speech), or in terms of combating recidivism.

It would be enough to hear out those who have actually gone to prison to realize that it is a toxic place, which favors new recidivism all by itself. Even seen in the best possible light, imprisonment can only serve to reassure public opinion on a symbolic level, or, at most, some higher-ups in the autonomous police trade unions.

It was precisely in the context of speaking about police unions that the Minister highlighted “the fact that arresting someone without them being imprisoned, and seeing the same drug dealer who was caught the day before on the same street corner the next day, also causes the demoralization of the police personnel, who are putting so much effort on their side and seeing their efforts nullified when we find them in the same place the next day.”

This is not sufficient motivation to crank up the repression machinery even further. The professional motivation of the police forces is an issue that must be paid attention to, but it must be reinforced in other ways.

In countries like Canada and the United States, decisions have been made to legalize cannabis, thanks to the crucial contribution of investigators and experts who have shown that the war on drugs is an old and useless approach. If we free ourselves from the obsession with punishment and from prohibitionist ideology, it might be possible to reorient both human resources (judicial and police personnel) and economic resources towards fighting other criminal threats that are much more alarming (for instance, mafia crimes, hate crimes or arms trafficking).

A police officer should not derive personal satisfaction from seeing the person they’ve arrested sent to prison. On the contrary, they should derive satisfaction from being universally respected as non-partisan public officials who are promoting and protecting the rights of all. Politics must ensure that they can perform this noble role.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/la-galera-non-e-un-regalo-alla-polizia/ on 2020-02-21