Reportage

The quantified self: When the body is an obsession

Millions of people are adopting a self-improvement philosophy known as the "quantified self." But who's really benefiting from all this data?

Sergio Bogazzi lives in Rome and is a computer expert with the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization. He has accumulated life experiences around the world. As a hobby, he collects data on his family: He records and analyzes their physiological parameters, physical activity, hours of sleep, and the daily habits of his wife and their three daughters. Based on his data, he has discovered which are the most annoying symptoms of his allergy, the times when his daughter most often gets sick with bronchitis and the criteria for scientifically selecting a neighborhood to live in.

Some readers might remember Furio, the character in the movie Bianco, Rosso e Verdone, who, before leaving Rome, would call the Italian Automobile Club to find out whether, at an average speed of 80-85 km/hour, he would leave behind the 982 millibar low pressure front. Instead, Bogazzi is part of a much trendier tribe than Furio; he’s an adherent of the so-called “quantified self.” Thanks to digital technologies, these individuals monitor the various aspects of their daily life and translate them into data to analyze.

The first core community was born in 2009 in California, inspired by futurologists Kevin Kelly and Gary Wolf, the founders and respected writers of Wired magazine. Since then, groups of self-monitoring digital enthusiasts have sprung up around the world. The University of Groningen in the Netherlands even houses a research institute dedicated to the topic. In about a month, the quantified selves will meet in Amsterdam for their world conference.

In fact, since 2009, the trend to voluntarily carry sensors that record our activities went far beyond the small sect behind Kelly and Wolf. Thanks to, or due to, “wearables,” electronic accessories that collect and exchange data on the internet. For example, the smartphones that almost everybody carries in their pockets are already collecting a wealth of information about how we spend our time, our social contacts and our movements. But the most popular wearables are those that go to on the wrist: smartwatches and special bracelets that double as gauges of cardio-circulatory information, sports activity and hours of sleep.

The product that dominates the market is the FitBit bracelet. It represents by itself around 20 percent of the market (about 23 million people wear it), and it generates revenues of over $2 billion a year for the eponymous San Francisco company that produces it. Its users expect that with their data at hand, acquiring and maintaining a healthy lifestyle will be easy. And it’s not just individual consumers who are interested in wearables. Many companies see an opportunity in the spread of these devices, mainly health insurance companies, startups and IT firms.

For private health insurance, it is easy to understand the appeal of self-monitoring customers. A device that assesses the physical condition of the insured individual, reports any eventual anomalies and provides real time advice on what to do, greatly reduces the risks for the insured person and, of course, also for the insurer. A diabetic patient, for example, can keep his blood glucose under control and avoid dangerous peaks. Several insurance companies, like the giant UnitedHealthCare, already offer discounts to customers who wear electronic bracelets. In addition, the available data allows companies to draw increasingly more precise profile of their customers so they can calibrate rates based on the real risk.

Something similar is already happening with cars. Insurance companies encourage the installation of GPS transmitters that measure the actual movements of the vehicles. But beyond the insurance sector, wearable devices are likely to contribute to a climactic change in public and private health systems.

The aging of the population, in fact, is increasing the incidence of chronic diseases that involve an ever more burdensome workload. Gadgets that measure the most important biological parameters and transmit them over the web can minimize the use of direct medical visits, limiting them to the most urgent and important circumstances.

Similarly, wearable devices will provide real-time advice to users — though a robot will hardly be able to satisfy the need for assistance that many people, especially older ones, can only satisfy with their primary care physician. Moreover, thanks to the permanent connection to the internet, the data collected from these devices will be analyzed and will generate new knowledge. This trend is in vogue around the world and goes by the name “telemedicine.”

Despite its name, telemedicine doesn’t just promise benefits for citizens. First, health administrators are very interested in it, because they hope it will reduce public health costs. In the near future, tests can be carried out without the knowledge of the patients and transmitted via the internet. In addition, it opens up completely new scenarios on the use of personal data of users.

To deliver on its promise, however, telemedicine requires efficient and pervasive technological infrastructure, accessible almost exclusively to large private companies specializing in the analysis and classification of users. And these companies are hungry for data.

The Italian government has partnered with IBM to start the health 2.0 project. The headquarters, which will be called the “Human Technopole,” will be in the area where the Expo was held in Milan. The agreement between IBM and the government has also aroused the interest of the Privacy Guarantor, since the IT company will have access to all the essential health data on Italians, from their health “curricula” to the DNA data of each of us. For IBM, it is an excellent opportunity to train Watson Health, its artificial intelligence system created to digest and analyze huge amounts of health data and provide more precise medical diagnoses.

Another giant of “profiling,” Google, wants to accomplish something similar. Its subsidiary Verily, in fact, has just launched a project called Baseline: For four years, 10,000 volunteers will provide data on their health every day. Each participant will be given a bracelet that registers physical activity and the main cardio-circulatory parameters.

In addition, the volunteers will undergo periodic examinations and genetic tests. All these results will be aggregated and analyzed by Google. The stated purpose is to collect data for biomedical research purposes, but there are many doubts about the actual effectiveness of the project.

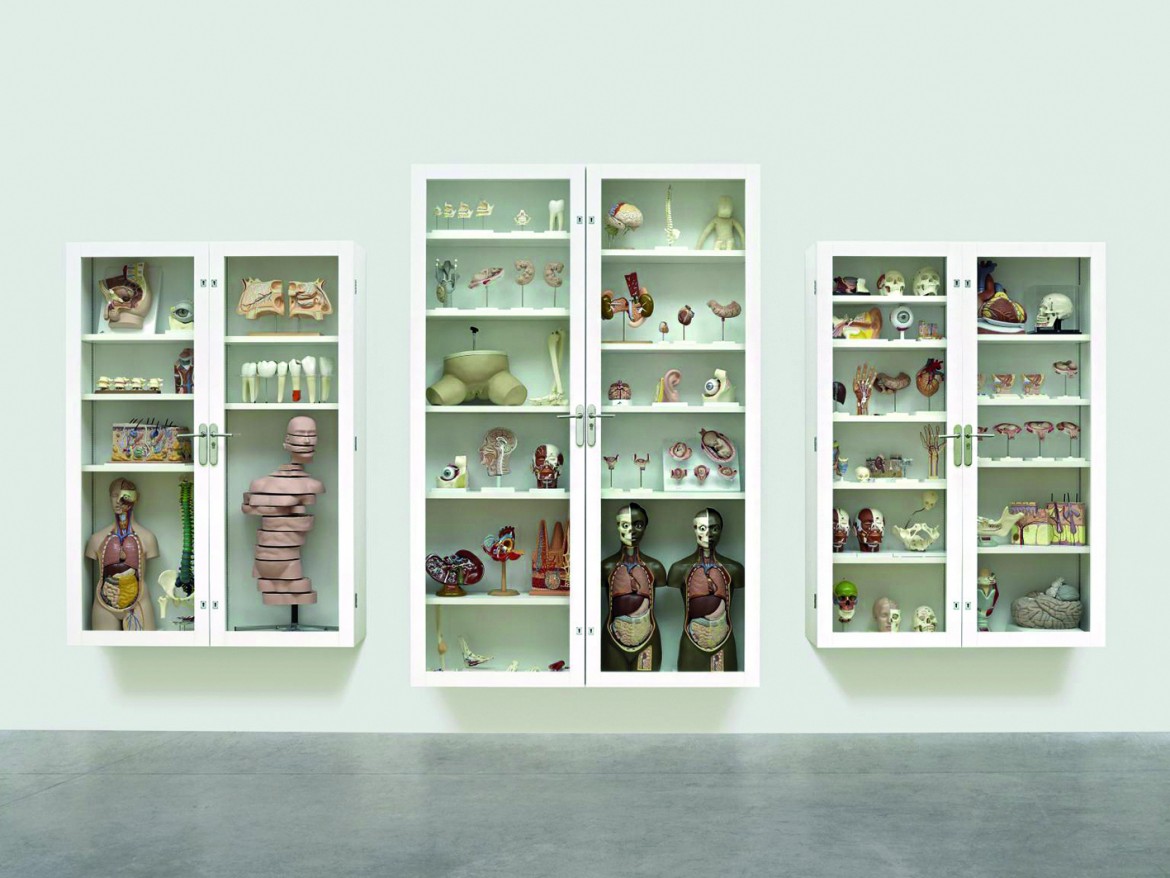

Wearable devices are not accurate enough for health standards. Furthermore, according to a 2014 survey, 30 percent of the bracelets are abandoned within six months of purchase. The users who will provide the largest amount of data, helping to redefine the concepts of health, disease and normal conditions, will be the most perseverant to the point of obsession. Don’t be surprised if, in place of the Vitruvian Man, within Leonardo’s circle of perfect harmony, you someday see the ineffable Furio with his bag.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/quando-il-corpo-e-unossessione/ on 2017-05-07