Commentary

Wael Zuaiter’s memory is precisely what is needed now

In his arms the doctor held a little girl who had just been killed, and when he saw me coming, he put her in my arms, looked into my eyes and said: 'This is how you’ll begin to understand the real history of Palestine.'

For me, Wael Zuaiter represents a beautiful memory, and at the same time a very painful one. I want to thank Tommaso Di Francesco for writing about this after such a long time (in Alias on Saturday, November 11) — not only because we Italians, in this moment of sorrow for Palestine, cannot help but quote Wael, who taught us the history of that country. But also because of a more “private” pleasure that we old and very old people from il manifesto experience, of whom there are few of us left: whenever we happen to find a precious shared memory like that of Wael Zuaiter, one almost unknown to younger people, we feel happy about that.

I got to know Wael back when it was still only a few people who knew the real history of Palestine. For me, the discovery came in ’67. It was a few weeks after the end of the Six-Day War, shortly after it ended with a cease-fire. I had been sent by Rinascita to attend the first of many useless conferences on the future of Jerusalem being held in Amman, and I knew nothing about the subject.

I only vaguely remembered the birth of the State of Israel in 1948 and the first foreign trip of the first Prime Minister of the new state, Golda Meir. It had been to Moscow, because the Soviet Union was among the very first to recognize Israel, and “Golda” was welcomed with great enthusiasm at the Moscow trade union building, where they all sang the International together.

It had all seemed normal to me: the influx of European Jews into that territory after the war included many comrades from the Kommunistisches Bund in Berlin, who left for that country to create a new left-wing state. As far as I knew, the ‘Arabs’ — without further specification — were right-wingers, tied to small feudal states sold to the British Empire. Otherwise, they were deemed nonexistent — both by the left-wing European Jews and by the right-wing ones, all arrogant Westerners. The trip to Amman was for me the beginning of a great discovery.

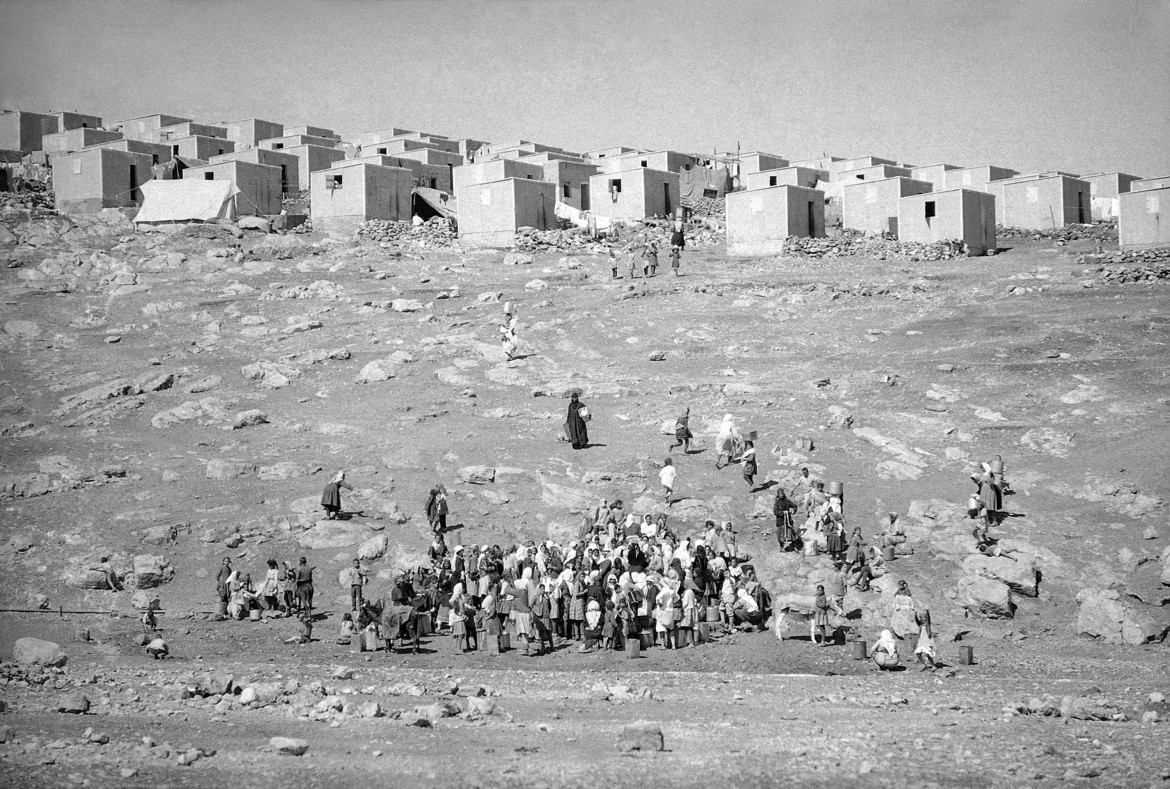

It was during that useless Jerusalem conference that a couple of Palestinians approached me and a British journalist and asked if we would be interested in visiting a refugee camp nearby. I still have on my wall a large photograph they gave me there: a view of the school with a cluster of children sitting in the sand.

Then our guides suggested another stop: a Jordanian town right on the border with Israel. But when we arrived, despite the cease-fire, a group of planes suddenly appeared in the sky and started bombing. They shouted to us to throw ourselves under the cars to shelter from the bombs. We hid there, myself and the English journalist — who were the most scared because we weren’t used to war — for about half an hour, then the planes turned back to Israel and we, safe and sound, all ran to the town hospital where those who had been wounded in the raid were already arriving.

At the door was a young Palestinian doctor, recently returned from the United States, where he had emigrated, to be there with his people. In his arms he held a little girl who had just been killed, and when he saw me coming, he put her in my arms, looked into my eyes and said: “This is how you’ll begin to understand the real history of Palestine.” Then he took me by the hand through the corridors of the hospital, where the newly-arrived wounded were already crowding, many of them on the floor, next to those who were already dead – just like nowadays, 56 years later, at Gaza’s Al-Shifa Hospital.

It was a turning point in my life, because from that moment on I would end up going back and forth between Amman, Beirut, Ramallah, Gaza, for decades. All until they grabbed me by the feet at the airport in Tel Aviv, dragged me on my back down the corridor and threw me on a plane to Milan with a stamp in my passport that read, “Persona non grata.” (With me was Claudio Sabbadini, the FIOM secretary; he went without having to be dragged, as he was unaware of the pacifist practice that says that in such cases you should sit on the ground and engage in passive resistance).

In ’67, when I came back from Amman, I wrote the article about the conference I had gone to and, of course, spoke at length about what had been a great discovery for me: Al Fatah and the guerrilla warfare that had begun. I had problems as a result: the Palestinian CP was against them (it would, however, change its opinion very soon), and the Communist party discipline then in force did not allow for opposing views. I published it anyway, albeit without the emphasis I would have liked.

Two days later, I was in my room at the Union of Women in Italy, where I had been sent when, after the eleventh congress of the PCI in 1964, the so-called Ingraian current was explicitly disavowed and many of us future writers for il manifesto were removed from Botteghe Oscure. I heard a knock at the door. It was a young Palestinian, who told me: “I came to thank you because you’re the first in Italy to mention Al Fatah by name.” It was Wael Zuaiter.

He became my constant go-between. With him I found myself in Amman, on the occasion of the tragic expulsion of Palestinians from Jordan, the famous “Black September” of 1970. And then I went to Munich, once again as a correspondent of il manifesto, back when we were no longer a magazine but had just become a daily. I spent a few days inside the Olympic enclosure, under the windows of the building where the Palestinian guerrillas had imprisoned the Israeli hostages. Heartbroken, we journalists all witnessed the tragic conclusion.

As soon as I got back to Rome, I ran to Wael to tell him about it, and we wept together — for that and for what had happened the day after the massacre of hostages and guerrillas: the great final celebration of the Olympics at the stadium in Munich, with the flags of all the states of the world. Only one was missing: that of Palestine.

I have written about these things because they make it clearer to me too, once again, just how serious the continuing lapses of the movement for peace have been. Just like when the Ukraine war broke out — when our sin was that we hadn’t followed and denounced what the West did after Gorbachev agreed to the reunification of Germany and the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact in exchange for limits to NATO expansion (a pact set out in writing, although secret). In this Gaza war, it’s that we’ve been distracted for years from what has been happening in those territories.

There’s only one thing I’m happy about — that we have the only UN secretary general who has ever said it: Hamas was wrong, but it didn’t come from nowhere, it was the result of everything Israel had itself done.

The other night, La 7 broadcast a wonderful report by Francesca Mannocchi. Watch it: it has many interviews with Gaza children among the rubble. When asked, “What do you want to do when you grow up?” they all answer, “Fight.”

We can’t do much, but let’s at least commit to telling those who aren’t paying attention the real story of Palestine.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/wael-zuaiter-la-memoria-necessaria-proprio-in-queste-ore on 2023-11-16