Interview

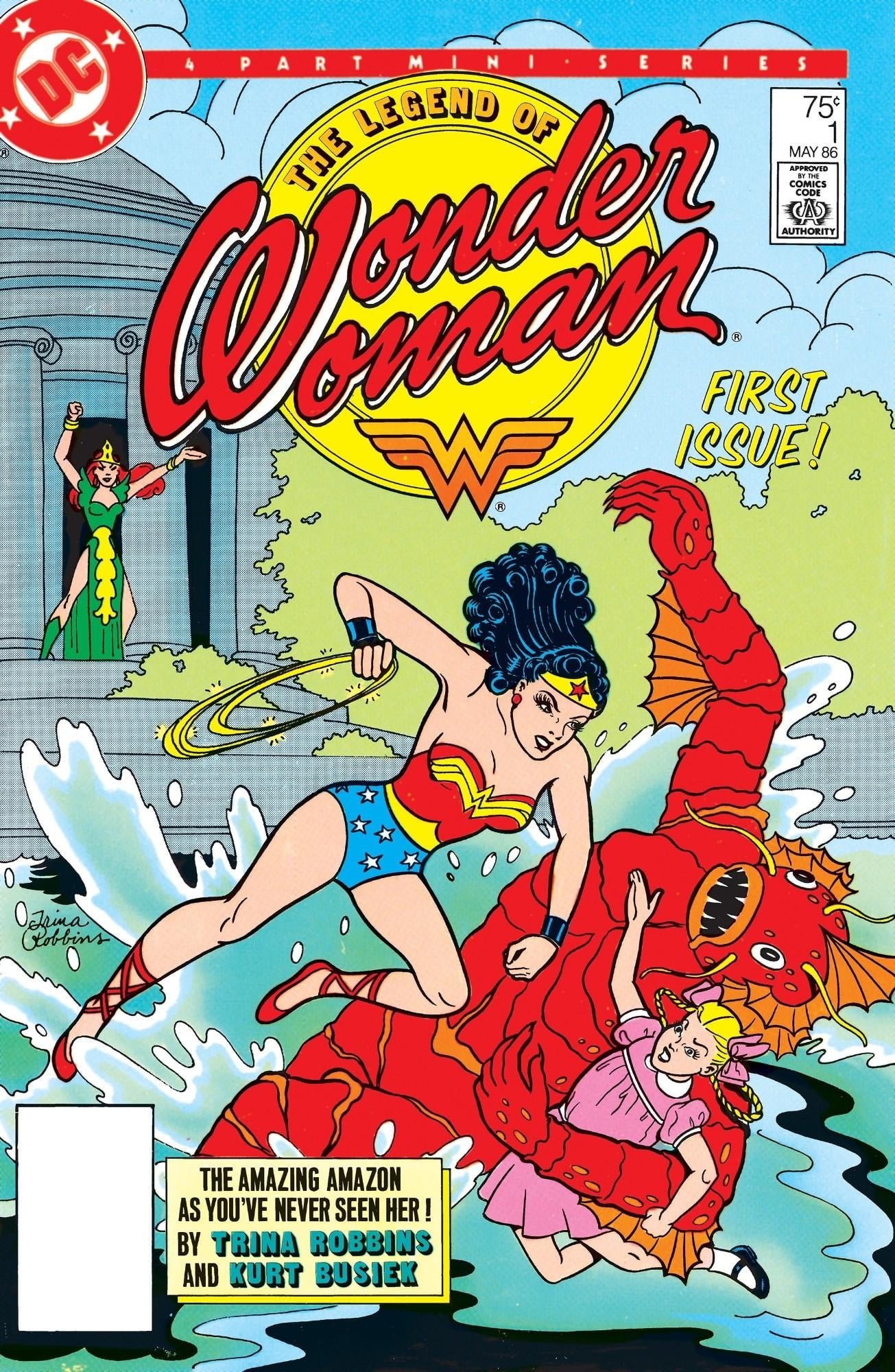

Trina Robbins navigated the boys' club of comics to become the first woman to draw Wonder Woman in her own solo mini-series

'It’s taken a century, but feminism is finally widely accepted in the USA by today’s young women, and WW’s time has come again.'

The recently issued graphic novel by Leigh Bardugo, Wonder Woman: Warbringer, and the upcoming feature film Wonder Woman 1984 directed by Patty Jenkins put the most iconic superheroine in the spotlight again. Both newly narrated by women, they take us back to the first woman to draw the Amazonian princess in her own solo mini-series.

Californian of adoption, Trina Robbins (Brooklyn, 1938) is very active and does not want to talk only about Wonder Woman, though she is fond of her. As a matter of fact she has a long and broad creative experience, ranging from being a protagonist of the female underground to historian of rediscovered woman cartoonists, from fashion designer to feminist activist.

You started your experience as a comics artist on the underground scene, first at the East Village Other, then moving in 1970 to the west coast. What was it like in San Francisco then?

San Francisco was the mecca of underground comics. All the publishers were located there — in 1970 there were already four publishers of underground comics. Unfortunately, there was also already a boys’ club that networked with each other and left me out. At that point, there were only two women drawing underground comics in San Francisco, or anywhere: Barbara “Willy” Mendes and me. I need to stress that it was not the publishers who left me out, it was the male cartoonists, who had a clique. Also, the many underground newspapers in the SF Bay Area did not leave me out — in fact, as soon as they learned I had moved to San Francisco, they phoned and invited me to contribute. It was the guys, plain and simple. It didn’t help that I objected to the misogynist comics many of them were drawing, and when I say misogynist, I don’t mean just naked women and sex — that wouldn’t and didn’t bother me — I mean humiliation and hatred of women, including rape, torture, and murder depicted as something funny. This was around the time of the Sharon Tate murders, and these guys thought Charles Manson was fabulous — they loved him!

And that’s when you focused on women’s comics. Could you expand on that?

Shortly after I arrived in SF, someone showed me an issue of the first feminist underground paper in the USA, It Ain’t Me, Babe. I immediately got in touch with them and very quickly I was taking the bus in to Berkeley every three weeks or so, helping with the layout and paste-up, and drawing for them. I drew front covers and comics on the back covers, and because I finally had the moral and creative support of the other Babe women, I felt strong enough to produce the first all woman comic book, It Ain’t me, Babe comics. All this while I was pregnant, and after I gave birth to my daughter, Casey. I did the color separations for the cover while I was nursing one month old Casey.

You were said to be quite critical about Robert Crumb. Do you still feel so and what for?

It was Crumb’s violent misogyny in his comics that was the biggest influence in underground comics at the time. He was a culture hero — he was god! — and the fact that I criticized his misogyny made me unwelcome and unaccepted in the boys’ club. I know he doesn’t draw that stuff anymore, but he is not the nicest of people, and he and his wife vociferously dislike me. In one interview he called me “a shrill little shrew.”

How was your passage from the underground to mainstream comics in the mid-‘80s, first at Marvel and then at DC?

Well, it sure was nice to get paid real money for my art!

DC is where you got involved with Wonder Woman in 1986. How were you interested in the character before that?

Wonder Woman was only one of all the women and girl-centric comics that I read as a young girl. I also loved Mary Marvel, who had all of Superman’s powers but was a girl. You didn’t have to wait to be a grownup to become a superheroine! And really, my favorite was Sheena, Queen of the Jungle. I wanted to live in a tree-house with my pet chimpanzee, wear leopard skin and swing through the jungle on vines!

How did you relate to Moulton’s masculine imprinting of the amazon warrior?

It wasn’t a masculine imprinting at all! Moulton was a female supremacist — he really believed that women were superior to men. The early WW comics are so women-centric! No men were allowed on Paradise Island, and hardly ever even in the comics: with the exception of dumb blond Steve Trevor, who was there so WW would have somebody to rescue. Even the villains were often beautiful women, who WW would send to “Reform Island,” to reform them. On the other hand, the male villains, like Mars, god of war, or the Duke of Deception, were ugly and deformed, and they never reformed. There was a fairytale element to the stories, also, with beautiful mermaids and winged women living on the planet Venus.

You have written a number of books about women and the comics. What has changed through the years? How do you see this issue today?

I started researching early women cartoonists because the men all said there had been no women drawing comics, and I knew that was untrue. The fact is that when you’re not written about, you’re forgotten, and all these talented women had been forgotten because none of the guys who wrote the comics histories were interested in researching and writing about them. So that gave me a nice hole to fill. It’s not always so good. Because of my books, people know about Tarpe Mills and Miss Fury, so, because she’s public domain, that has led to some ghastly comics in which Miss Fury is drawn in “bad girl” style with brokeback poses. And because of my books, original art by Nell Brinkley, which used to be affordable back when only a small cult following knew about her, has led to her art going for sky high prices. Good thing I found my Brinkley originals back before she became so well known!

Back to Wonder Woman, what considerations do you make of the development of the character following your treatment up to date?

Unfortunately, because she’s a comic character and not a real woman, WW has been a slave to whoever writes and draws her, so she went through some bad periods where her bust size drastically increased while her costume drastically decreased, and the writing wasn’t so hot either, written by various guys who simply didn’t understand or care about her, sometimes I think, even actively disliked her. But in between there have been some very good writers, Gail Simone and William Messner Loebs, being my two favorites, and since the movie, some very good art and writing, by both women and men.

And what about the TV series and feature film versions?

I loved Lynda Carter as Wonder Woman! I think she personified WW just like Irish McCalla personified Sheena on TV in the ‘50s. And the movie was of course magnificent.

The more recent graphic novels and movies of WW are made by women. Do you think that’s a must?

Any good writer or artist — male or female — who loves and understands WW, can do a good job writing or drawing her. But you have to love and understand her, and you have to be a good writer or artist.

How do you explain the great return of popularity of WW today?

It’s taken a century, but feminism is finally widely accepted in the USA by today’s young women, and WW’s time has come again.

To end, what mostly attracts your attention lately?

I’m still writing — writers don’t have to retire! I’ve contributed to a number of comics anthologies recently, and want to script more comics and graphic novels. I love to write! And there are still talented early 20th century women cartoonists to be written about. I’m very proud of my latest book, The Flapper Queens, featuring the art of women cartoonists of the Jazz Age, and January will see the publication of my book on Gladys Parker.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/trina-robbins-la-militante-che-disegno-wonder-woman/ on 2020-10-03