Feature

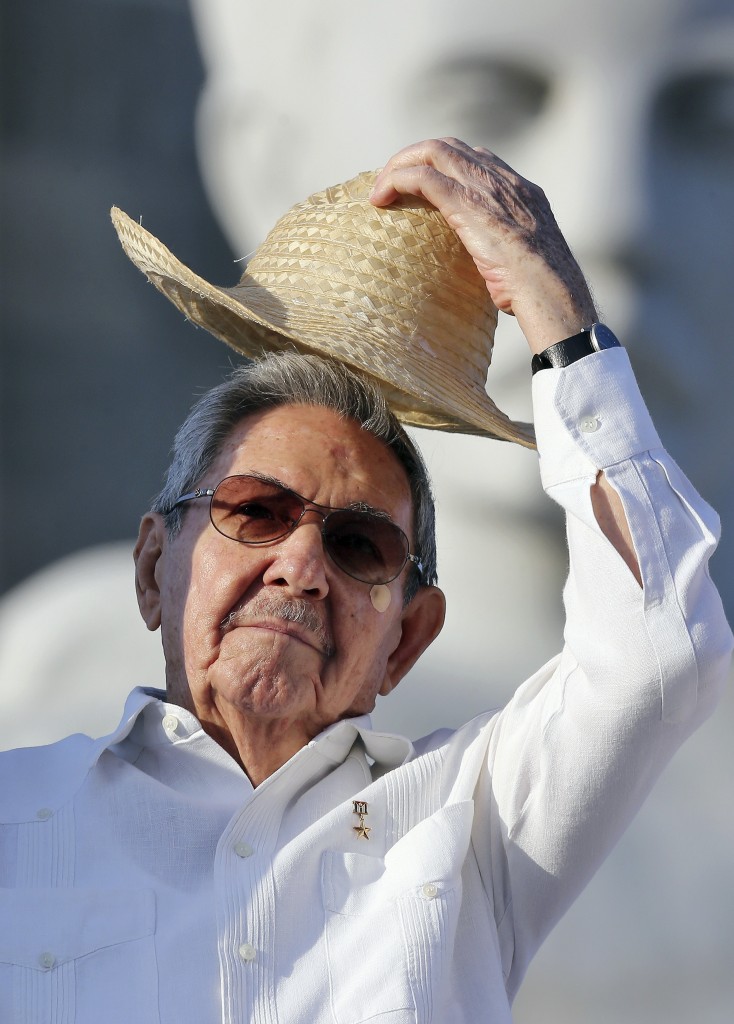

The ‘tough guy’ who first opened Cuba to the world

Raúl Castro has shown himself to be pragmatic and cautious—perhaps too much so—as a manager of the political transition.

He was thought to be a “tough guy,” and that he would champion some sort of Cuban-style “militarized socialism”—and instead ended up being the leader who met with Obama in Havana in March 2016, and who presided over the broader economic reforms launched after 1989 (the year that marked the end of the relationship with Moscow).

He has ruled the island since 2008, preparing for a new generation to succeed his brother Fidel, the founding father of modern Cuba, whose funeral he oversaw in late November 2016. The alarmists were proven wrong as usual. Raúl Castro has shown himself to be pragmatic and cautious—perhaps too much so—as a manager of the political transition.

Biographers and historians have always struggled to draw up a full portrait of him. While he fulfilled important roles ever since the early fights of the guerrillas in the Sierra Maestra at the end of 1956, he has always preferred to remain in the shadows, until 2006 when Fidel’s ill-health began. Accordingly, people had become used to writing about the younger of the Castro brothers as the “operational arm” of Fidel, denying him a role in policy development and influence in the strategic choices of the Revolution.

Born on June 3, 1931, in Birán in Cuba’s far east, like Fidel himself, he is known to have followed in the footsteps of his older brother, pursuing higher education in Havana at the Collegio Bélen, a Jesuit institution. But the young Raúl did not like the excessive discipline at the school, and his grades in the first year were not good.

His father, Ángel Castro, withdrew him from the school. In 1953, unlike Fidel, who had chosen to be a militant for the Orthodox Party, Raúl became a part of the Socialist Youth (the youth organization of the Socialist People’s Party, the Cuban Communist Party of the era). In March of the same year, Raúl left for Europe: Vienna, Prague, Moscow. Upon return, he was arrested and expelled from the university for his political activism.

When he was reunited with Fidel, the plan to attack the Moncada Barracks in Santiago was already well underway. On July 26, 1953, the date of the first attempt at an insurrection against the regime of Fulgencio Batista, Raúl was given the task to occupy the Palace of Justice in Santiago. In June 1955, an amnesty was granted to the youth of the July 26 Movement, and Raul was the first to go into exile in Mexico. It was in Mexico City that the future Minister of the Armed Forces became friends with Ernesto “Che” Guevara, and he was the one who introduced him to Fidel.

At the end of 1956, Raúl was one of the 82 men who returned to Cuba aboard the small yacht Granma, and a veteran of the first clashes with Batista’s army. He was given the rank of comandante. In February 1957, the first group of women joined the guerrillas in the Sierra Maestra. Among them was Vilma Espín, who would become his wife.

As Raúl himself recounts: “When I entered Havana (…) I was convinced that it was mostly over. We had defeated the Batista dictatorship, we could start living a normal life. But Fidel called us together and warned us that the revolution had only just begun. He told us that it was necessary to build a new society.”

Raúl was the one who established an enduring relationship with the USSR army, who in the Sixties provided Cuba with weapons, technology and technical staff, and he gained a reputation as the most pro-Soviet of leaders of the Cuban Revolution. As for his reputation as “tough,” he explained at one point: “I do not have the charisma of Fidel. My brother helped build up my image as tough at the beginning of the Revolution, when plots against him were discovered. He told everyone that if he were killed, the situation would become even more difficult, because I would be the one to take his place.”

Those who have worked with Raúl describe him as methodical, efficient, with a great capacity for work and organization, and inflexible in denouncing what he does not like and ousting anyone who betrays his trust.

In a speech in Santiago in 1979, he was the one who coined the term “sociolismo”, contrasted with true “socialismo,” to denounce the favoritism, lack of discipline and bureaucracy of the “socios” (Party members) in the political and economic life of the island.

The most sensational episode in which he played a leading role was undoubtedly the events of June 1989, when General Arnaldo Ochoa was arrested, a hero of the Cuban operations in Africa and about to be appointed head of the defenses of the city of Havana (more or less No. 2 in the hierarchy of the Cuban army). Ochoa was accused of having “covered up” illegal trafficking in drugs and foreign currency, and, at the end of a trial that did not manage to clarify all the details of the events, was sentenced to be shot.

In subsequent years, Raúl would reorganize the two ministries in his area of responsibility after the damaging event of the Ochoa affair. Despite his hardliner reputation, he welcomed the first timid attempts towards introducing a mixed economy and tourism. Out of a branch of the FAR (the Revolutionary Armed Forces), the Gaviota company was established, which began to manage hotels, joint ventures and tourism services. Raúl’s role in these developments was crucial in the mid-nineties.

In August 1994, the “Rafters Crisis” broke out: thousands of Cubans were leaving the island on makeshift crafts in response to the severe economic crisis. Raúl, the Minister of the Armed Forces, was the one to announce the government’s first line of response to the crisis: the liberalization of the agricultural market. Raúl was the public face of the decision—a gesture interpreted by many as a direct assuming of responsibility, viewed in contrast with Fidel’s hesitations towards introducing a mixed economy.

Now, after handing over the reins of the government, he will remain Secretary of the Communist Party. He will likely be living in Santiago, in semi-retirement.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/il-duro-che-ha-aperto-cuba-al-mondo/ on 2018-04-19