Commentary

The streets are full, but the ballot boxes are not

Social power is not a monolithic and unchanging substance; it is the result of at least three elements that have been combined in various ways throughout history.

Two recent events illustrate the paradox of democracy nowadays.

The first: on September 22, Italy came to a standstill for a day that will remain in collective memory, as hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets in over 80 cities. It was a mobilization that established power could not ignore.

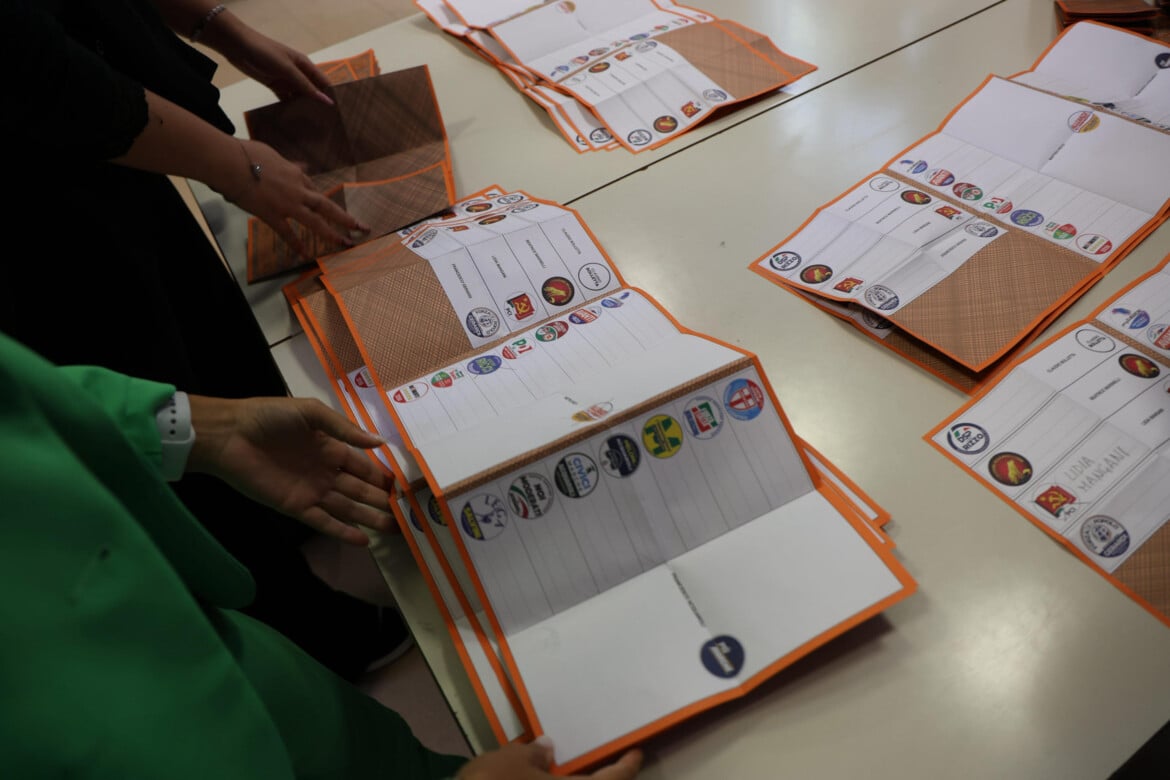

The second: the regional elections in the Marche region re-elected the incumbent regional president, Francesco Acquaroli, supported by a right-wing alliance, who won with 52.4% of the vote. It was a clear victory, although with a smaller margin than five years ago. With turnout at just 50% – a drop of nearly ten points since 2020 – the election revealed another aspect of the region’s politics: an ever-growing gap between citizens and the ballot box.

These two events call to mind the famous adage of Italian socialist leader Pietro Nenni: “Full squares, empty ballot boxes,” a phrase quoted by many after the election results. At first glance, the general strike seemed to have restored the agency of social power by bringing its different elements together in a way not seen for at least two decades. On closer inspection, however, the current-event-driven nature of the coalition that filled the squares provides the key to understanding why the proverbial ballot boxes remained empty. The September 22 mobilization was no ordinary protest. It was driven by the moral conviction of those who chose to show up to protest the horror in Gaza. For a moment, this cause partially brought together the fluid elements of social power that have been fragmented since the end of the 20th century.

Social power is not a monolithic and unchanging substance; it is the result of at least three elements that have been combined in various ways throughout history. First is organizational membership, which refers to the stable organization of a base, with rules, dues-paying members and a leadership class. Second is mobilizing political capital, which is the ability to shape public discourse, bring people into the streets and produce images and words that can spread and persuade, regardless of membership numbers. Finally, there is effective influence, i.e. the tangible impact on institutional decisions and public policy.

For most of the 20th century, these three elements were contained within a single model. Membership numbers guaranteed a public voice, which in turn became a force at the negotiating table through the exchange of electoral support for public policy decisions. This is how the democracy of industrial-age citizenship worked – with all its flaws and limitations, but with a recognizable order. Today, that model has dissolved.

Membership in interest-representation groups is now mostly driven by the demand for services, which these organizations began providing once they abandoned social conflict. Membership in today’s political parties, especially the heirs to the great mass parties of the past, is dwindling or is driven by the pursuit of individual benefits. Transformed into mere electoral committees, they are primarily concerned with their media positioning and care little for territorial roots or the organizational dimension of politics.

Mobilizing political capital has been dispersed among atomized movements, digital campaigns and influencers who create public agendas that shrink into “political bubbles,” incapable of tapping into the broader mechanisms of support. And effective influence has become concentrated elsewhere: in the smoke-filled rooms of technocracies, where budgets and regulations are decided, in the pressure exerted by specific lobbies, and in the financial markets, often with no democratic mandate and completely bypassing representative bodies.

One of the most important aspects of the general strike was that its massive turnout showed this separation is not inevitable. For once, at least two of the three elements of social power coalesced. The mobilizing political capital – generated by grassroots unions, peace movements, radical left groups and volunteers, as well as the many individuals who participated on their own – fueled effective influence through direct pressure on the government and political class, which had to reckon with the fact that it could no longer dismiss the conflict.

What was missing, however, was the “card-carrying membership” aspect of the traditional, mainstream unions and political organizations, which are now scrambling to regain ground.

And the exception is not enough to change the rule. Beyond the unique circumstances of September 22, social power remains fractured. In this one can see one of the primary sources of the current democratic crisis: the lack of political forms that can reunite organizational membership, mobilizing capital and effective influence. The empty ballot boxes in the Marche elections are a consequence of this, beyond and independent of the “alliances of circumstance” of political parties that are failing to inspire a tired electorate.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/il-vuoto-della-politica-che-non-sa-leggere-le-piazze-sindacali on 2025-10-01