Commentary

The possibility of change between the politics of hope and memory

This is why it is so difficult to write about hope nowadays. Because we are weighed down by the dead hand of memory, which seems to deny any possibility of change.

Can one still write from the perspective of hope in an age of memory? In the early 1960s, historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. answered this question in the affirmative.

In his view, the United States was finally emerging from a period dominated by moralism, and by the complacency that had defined the years of the Eisenhower presidency, and was moving toward an era of idealism and cultural openness, thanks to the leadership of a new ruling class. Schlesinger expressed this conviction from a peculiar standpoint: not as an academic – he was a professor of history at Harvard – but in his new capacity as “special assistant” to President John F. Kennedy.

His reflections on the dialectic between memory and hope are found in the opening pages of The Politics of Hope, a collection of essays that aspired to be a kind of cultural manifesto of the “new frontier.”

Schlesinger had inherited from his father, who was also an influential historian, a cyclical view of U.S. history. The rise of Kennedy – young, intellectually articulate, progressive – had appeared to him as a confirmation of his father's intuition that saw the beginning of the new decade as the start of a liberal cycle after the conservative dominance of the 1950s.

However, history often makes historians eat their words, especially if they venture onto the slippery ground of making predictions about the future (as both Schlesingers did, father and son). The Politics of Hope was published on New Year's Day in 1963. Before the end of that year, JFK would be dead. In the official account, he was assassinated by Lee H. Oswald, who had acted alone (this was the conclusion reached by the Warren Commission, appointed by Kennedy's successor, Lindon B. Johnson); but he may have been the victim of a conspiracy in which sectors of the state apparatus could have played a role (as claimed by thousands of adepts of a wide range of conspiracy theories, but also by reputable journalists like Jefferson Morley). No matter what account one gives of what happened on November 22, 1963, there is no doubt that the president was far from the only casualty in Dallas.

Within a few years, Schlesinger himself was forced to admit that the liberal hope whose advent he had enthusiastically heralded had not survived the death of JFK for long. After the wound in Dallas, that hope was dealt a dual deathblow by Vietnam and the sinking of the “Great Society” promised by Johnson. As early as 1967, a new book by Schlesinger on liberalism in the 1960s bore the title The Bitter Heritage, and the worst was yet to come, both for the Kennedys (Robert would also be killed, by another lone assassin, in June 1968) and for “new frontier” liberalism.

Why recall these events from so many years ago now? It’s not so much out of annoyance at the spirit of the first days of a new year, which, under a regime of triumphant capitalism, dissolves both hope and nostalgia into a molasses of resolutions and admonitions, but rather out of curiosity about what that distant season can teach us. People born after JFK's death are familiar with another season of triumphant liberalism, the one that followed the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the dissolution of the Soviet bloc. Those of the right age will also recall the establishment of a political vision on the left that, in some ways, harkened back to the “new frontier”: neither socialist nor conservative. Progressive and liberal, centrist and reformist.

And those who are younger have had to learn to live with the consequences of the betrayed promises of that new season of liberalism. The dismantling of the “machine égalitaire” (“egalitarian machine”) of social democracy and welfare, as Alain Minc called it in one of the books that heralded that revised version of the “new frontier,” didn’t give us a more equal society thanks to the benefits of the market, but a weaker democracy thanks to unfettered capitalism. This is why it is so difficult to write about hope nowadays. Because we are weighed down by the dead hand of memory, which seems to deny any possibility of change and legitimize mockery of those who persist, in spite of everything, in reasserting the principles of freedom against those of necessity.

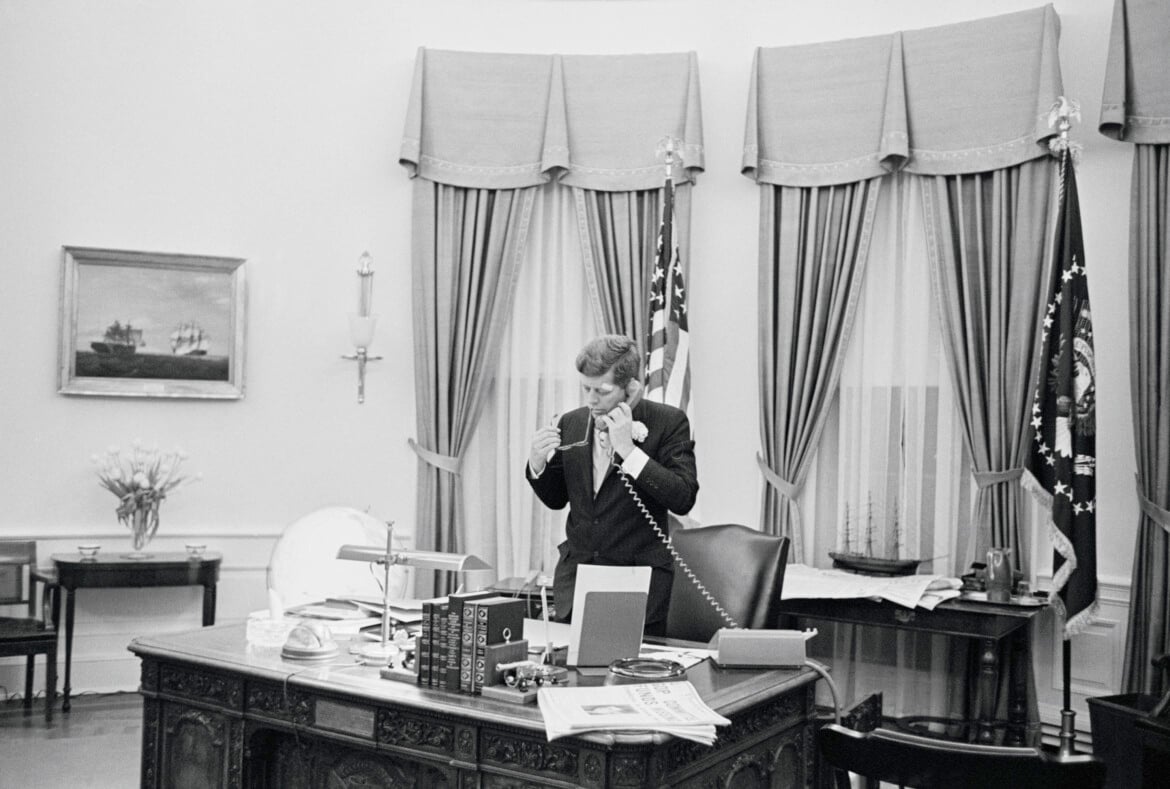

In the 1960s, the politics of hope succumbed because of an angry, violent and ruthless reaction, not so much and not only against JFK, but against what the Democratic president had come to represent, partly in spite of himself: the final overcoming of racial segregation, a more equitable society, a world of peaceful coexistence and justice. One of the most beautiful images of the Kennedy presidency has come to us thanks to photographer Jaques Lowe. The photo, dating from 1961, shows JFK talking on the telephone, his right hand covering his eye as if he had taken a punch, his expression pained: he had just received news of the killing of Patrice Lumumba.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/la-possibilita-di-cambiamento-tra-politica-della-speranza-e-memoria on 2025-01-03