Commentary

The political elite are steering us to national suicide

Neoliberal reforms have gutted our towns and downplayed history and geography in schools. Italy’s unification was the most important achievement in its modern history. Now Italy is setting in motion its own disintegration.

I am now fully convinced that in no other historical phase, at least in modern times, have the Italian ruling classes—especially the political class—expressed such a determined will toward self-destruction, such an obvious “death drive,” as we have been seeing for some years now.

The signs of our country’s downward slide toward national suicide are obvious and plentiful. The first and most striking one is the unyielding war being waged against the youth. A country of the elderly, where fewer and fewer babies are being born and more and more old people are becoming unable to care for themselves, offers the new generations a future of unemployment and precarious jobs, throws a thousand obstacles in the path of youth who want to attend university, and forces the best minds to seek their fortune elsewhere in the world.

It is a country that is being depopulated, with towns and villages, farmlands and forests being abandoned wholesale, just as it declares outright war against the poor youth of the global South: the migrants who are coming to the Peninsula and who could be a source of revival. See, for instance, what has happened in Riace.

Italy’s unification, which only came late and after many sacrifices, was the most important achievement in its modern history—to quote the opinion of a historian who is certainly not on our side politically, Rosario Romeo. Now Italy is setting in motion, in concrete terms, its own disintegration, with the increasing degree of autonomy that has been granted to the Veneto region regarding taxes and other matters.

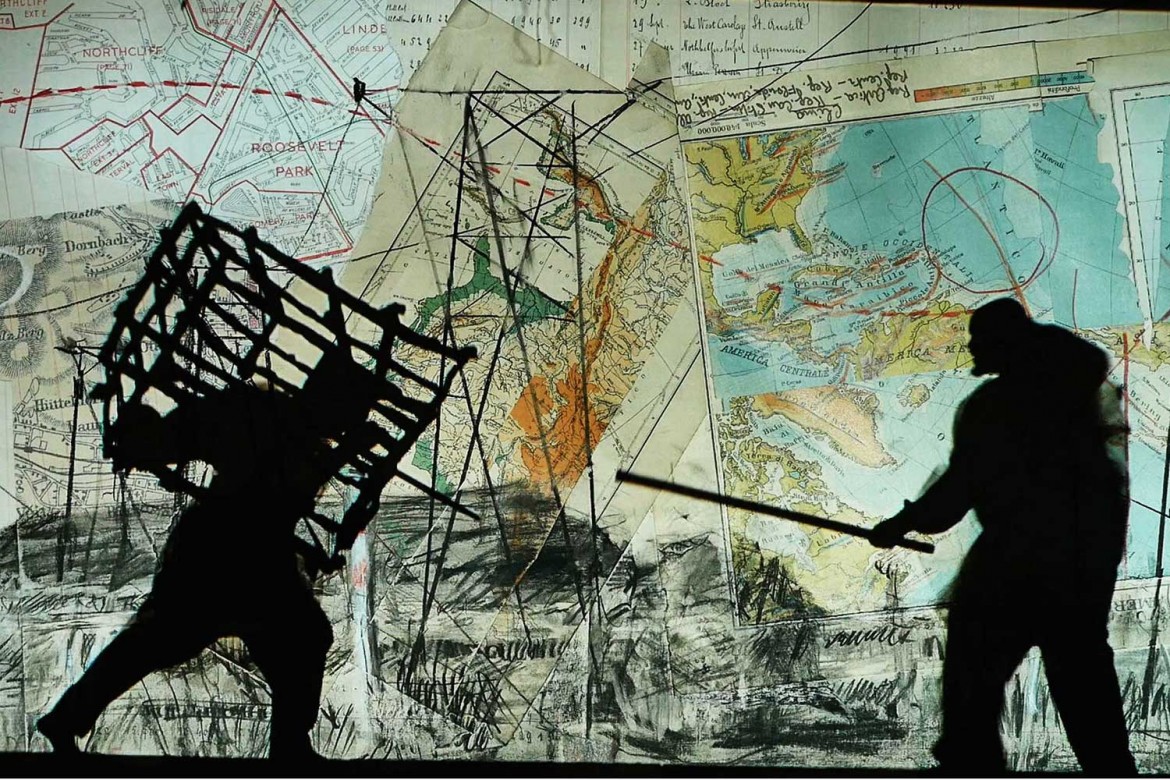

Meanwhile, the Italian ruling classes have for a long time been setting up just the right cultural assumptions to provide the most suitable means for making this national suicide a reality. Think, for instance, of the removal of geography as a subject matter taught in schools. In any other school system in the world, such a move would be immediately seen as outrageous and absurd, especially at a time when the world’s geography, with its movements of peoples, natural disasters and climatic upheavals, is coming into our living rooms every day via the news.

In Italy more than anywhere else, the marginalization of this discipline represents a real act of cultural mutilation. No country in Europe, with the partial exception of the Netherlands, depends so much on the local characteristics and the healthy condition of its territory. From the Alps to Sicily, over a stretch of 1,200 km, there is no other European nation that can boast of such a variety of habitats, climates, topography, rainfall patterns, river systems and local land characteristics.

From this “mosaic” of territories, together with our unique history, the global uniqueness of our agriculture was born—as well as that of our cuisine. Shouldn’t the new generations know about the original features of the country they live in, which are such an important factor to its present condition?

The latest act of this thoughtless strategy of cultural self-mutilation was the Ministry of Education’s decision to remove the discipline of history from the high school exit exams. This is an explicit invitation to our kids to give a lower importance to this discipline during the course of their studies, which are more and more focused on the final exams. The history test will be replaced with one focused on contemporary issues: after all, the reasoning goes, the pressing issues of today are simply too important and too urgent to waste time studying facts and events from many years ago.

This decision is the very quintessence of the “modernization” process that has been in effect for some time now, part of the neoliberal reform of education, which is certainly not just an Italian phenomenon. The school system must “keep up with the times”—which means that it must be incorporated into the mechanisms of economic development, become aligned with, and a preparation for, the labor market, and become immersed in the flow and the ways of thinking of the information society and the entertainment business.

Is this really supposed to be an improvement? Can the marginalization of history and the narrowing of minds to the present moment offer the new generations a way to extricate themselves from the vagaries of the present and become aware of the deep historical currents that are influencing what is happening nowadays, so that they would learn what must be done for the future?

Without history, without the profound perspective that the past offers us, the present will always give the impression of being a natural phenomenon, an immutable reality and the only possible one—an artifact without causes and without authors. Without history, no one can understand how and why we have gotten to this point, and no one can see a way out for the future.

I cannot help but wonder: haven’t we already collectively agreed on the fact that without historical knowledge—without an awareness of the different worlds of the past, without the knowledge that every “present moment” is merely a transitional process, a human artifact—any project of a common society is simply impossible? Perhaps the ruling classes are trying to convince the younger generations that the idiotic, relentless chaos of now, which they are no longer able to govern in any meaningful sense, is in fact the only possible world.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/la-vocazione-al-suicidio-delle-classi-dirigenti-italiane/ on 2018-10-25