Commentary

The long gaze of the exiled children

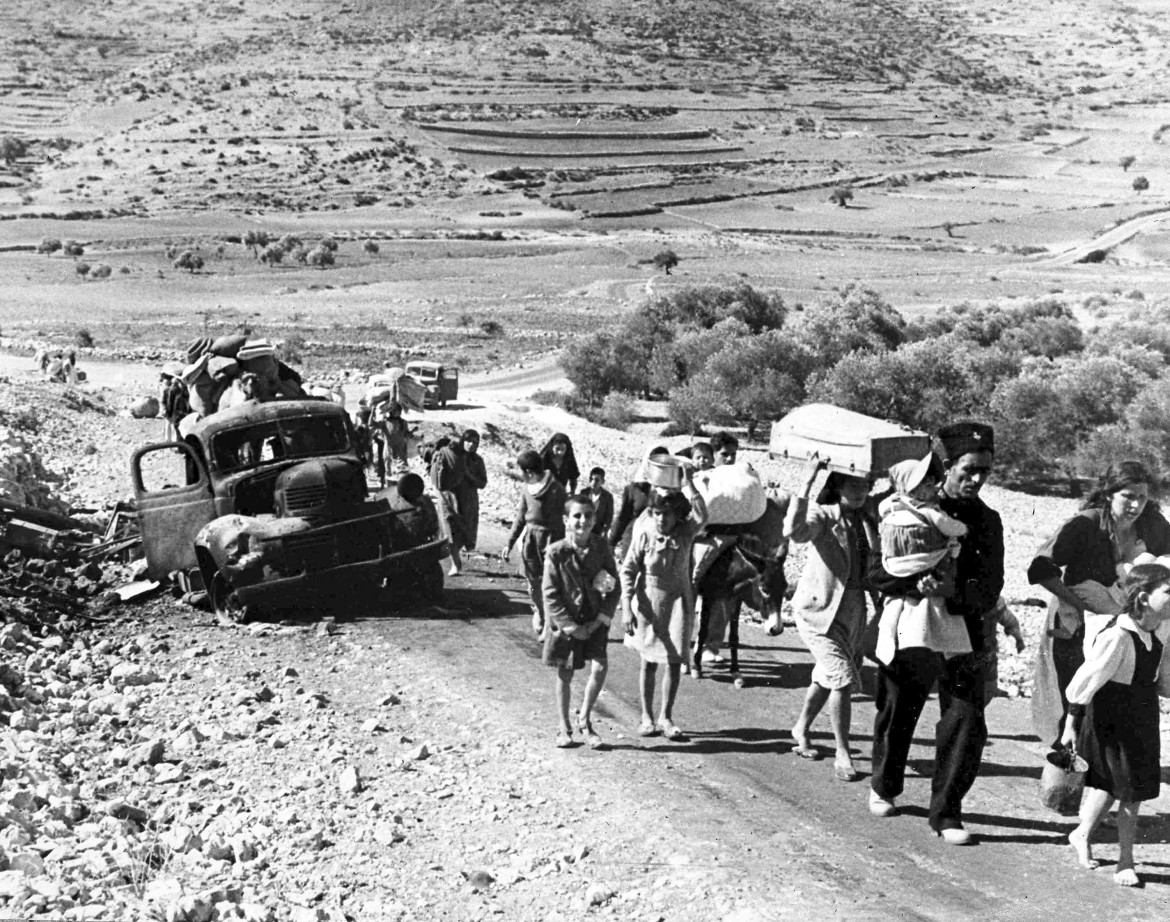

The Palestinian people, refugees in their own land and without rights, resume their journey once again, for an impossible exodus. How will they ever be able to return if there will be scorched earth in Gaza for revenge?

As we write, the Nakba of 1948 is repeating itself for the Palestinians. Those events were retold in a great novel by the Israeli writer S. Yzhar in 1949, where the narrator, a Jew who was taking part in the expulsion of the Arabs, eventually rebels after a realization:

“…At that point, we saw a woman passing in a group of three or four others. She was holding the hand of a child, maybe 7 years old. There was something special about her. She seemed resolute, blind in her grief but controlled. Tears ran down her cheeks, almost as if they were not her own. The child groaned with tight lips, as if to say, ‘What have you done to us?’ It suddenly seemed that she alone knew what was going on there, so much so that I felt ashamed in her presence and lowered my eyes. It was as if a cry was going up from her footsteps and those of her son, a kind of hate-filled curse. We also noticed how proud she was of not affording us the slightest attention.

“We understood that she was a mother-lioness, and we saw that the effort to restrain herself and behave heroically hardened her facial features, and that, now that her world was gone, she didn’t want to collapse before us. Elevated by grief and sadness over our wicked nature, the two of them passed on, and we saw how something was happening in the child’s heart, that same little one who cried disconsolately: once he grew up, he could not become anything else than a viper. It all became clear to me, as in a flash. Everything suddenly seemed different, the lines more clearly drawn: ‘Exile, that’s it, that’s exile. This is how it happens.’”

This comes at the end of a short but great novel published in 1949 in Israel, practically the first in Israeli literature, written by S. Yizhar (Yizhar Smilansky), rightly considered the founding father of Israeli literature, which provoked a great debate in the newly formed state of Israel.

The novel (translated in Italy for Einaudi under the title La Rabbia del Vento – “The Rage of the Wind”), was originally titled Khirbet Khizeh, the name of a fictional Palestinian village that became Israeli through violence. It’s all a stand-in for the Nakba, the “Catastrophe” of 700,000 Palestinians driven from their lands in 1948, but experienced through the eyes of a narrator on the side of the Jewish brigades – Golani, Irgun, Haganah – who rounded up Arabs, razed their homes to the ground with dynamite, murdered them indiscriminately and were engaged in ethnic cleansing to drive the Palestinians out.

Extraordinary in its literary form – a dialogic confession – it belongs to the great tradition of “draftee” novels, which express an objective opposition to the irrationality of war by describing the point of view of the men who become soldiers. Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead is a famous example, as is Celine’s Cannon-Fodder, but we could list many others, which have also inspired many famous movies (from Platoon to The Thin Red Line).

In this particular novel, however, the author stands out both for his art and courage: he goes against the current to the point of taking on the pain of the “enemy” as his own. It culminates in that bitter and terrible realization of the narrator, whose fellow soldiers had just reminded him that many new Israeli cities would be built in those places.

Struck dumb by the menacing eyes of a child, which can only become like that if they absorb the evil in their surroundings, the protagonist clashes with the others in the platoon and monologues to himself: “My insides were screaming. Colonialists, they screamed. Liars. Khirbet Khiza is not ours. A Spandau machine gun can never confer any rights. Oh, oh, screamed my insides. What they didn’t tell us about the refugees. Everything, everything for the refugees, for their welfare and protection… Of course, our refugees. But what about those we condemned to be so… Two thousand years of exile. Why not. They were killing Jews. Europe. Now we were the masters.” Then, loudly, though in a shaking voice, he shouts at the platoon members laughing at the Palestinian refugees: “We have no right to send them away from here!”

Seventy-five years later, that story is being repeated in our times, with the Israeli government and military’s ultimatum to one million people, sending them away deeper into and beyond the Gaza Strip – to where? The Palestinian people, the people of the refugee camps, refugees in their own land and without rights, resume their journey once again, for an impossible exodus with no return. How will they ever be able to return if there will be scorched earth in Gaza for revenge?

Now the eyes of children are watching us. Those who manage to survive the ongoing atrocities – no matter on which side. After the massacre by Hamas, which, not content with the heinousness they’d shown, saw fit to film the horror of mangled child bodies to replay it to us in a media slaughterhouse; and after the broken lives of 614 Palestinian children killed by Israel’s gunfire and air raids so far, according to UN sources. We prefer to be silent about these, because we continue to think that killing with advanced technology, with sophisticated and deadly weapons, from high in the skies is somehow (for reasons no one can explain) more legitimate and aseptic, less criminal.

One thing is certain: we are without a future. At this point, unless the current war is stopped, we can no longer delude ourselves that the children will save this world.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/lo-sguardo-lungo-dei-bambini on 2023-10-15