Analysis

The linguistic scam of Italy’s ‘citizenship income’

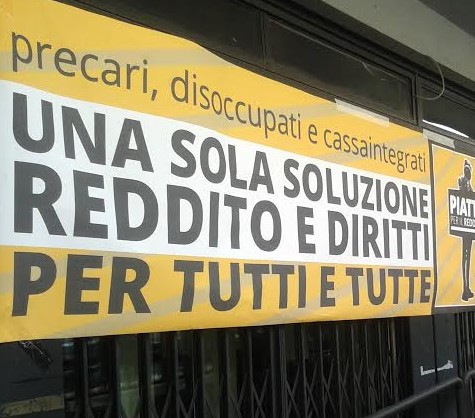

The ‘citizenship income’ proposed by the Lega-M5S government doesn’t have any of the traits of universality, justice, equitability and unconditionality. It is a workforce reintegration benefit of last resort for the unemployed, temporary workers and the poor.

The poverty benefit misleadingly called a “citizenship income” is to be the top achievement that the M5S will tout for the European elections in May. What has been included in the soon-to-be-approved budget law is nothing but a sham and a deliberate misuse of words.

A real “citizenship income” is not tied to an obligation to work and has nothing to do with the disciplining and punishment of beneficiaries which prominently feature in this M5S-Lega version of “workfare,” which apes the worst features of the Hartz IV German system. They are talking about a new category of so-called “citizenship crime,” with up to six years in prison in case of fraud. The benefit will be tied to eight hours of unpaid work per week, to compulsory training, and to the profiling of the purchasing patterns of 3.6 million of the “Italian poor.” It may also be available for foreigners who have been residents for at least five years, if the Lega allows it.

This benefit doesn’t have any of the traits of universality, justice, equitability and unconditionality. It is neither a “universal income” nor a “citizenship income.” It is a workforce reintegration benefit of last resort for the unemployed, temporary workers and the poor, part of the authoritarian turn of the welfare state and active labor policies (coercive and compulsory) aimed at the creation of one or more parallel labor markets. Germany’s “mini-jobs” pioneered this approach, and more measures of this type are in development.

Furthermore, the project is linked to an unrealistic reform of the public unemployment services that is planned to be done by April 2019. This bureaucracy—with details still under discussion after the recent meeting between Di Maio and the representatives of the regions—will need to fulfil the task of matching job supply with job demand at the national level, no longer at the provincial level. As Di Maio himself pointed out in an interview before the election, on January 4, 2018: “Once a job is found that is suited to the individual characteristics of the citizen, they cannot refuse the job offer, or they will immediately lose the benefit.”

The duration of the benefit is also unclear and uncertain. It was said at first that after the first twelve months, the so-called “income” would gradually diminish to zero. Then, there was talk about 18 months. Later on, the figure of three years was mentioned. In the absence of the text of an actual bill—which should arrive in a legislative package with the budget law, if it ever does—we can only rely on the occasional statements by those in government. The debate on the individual duration of the benefit seems to assume the presence of circumstances that are at present unknowable. First of all, economic growth: as forecasted in the budget law, between 2018 and 2019 this should rise from an estimated 0.9 percent of GDP this year to 1.5 percent for the next year. Everyone is skeptical about this forecast, because the trend over the past two years has gone in the opposite direction, towards a decrease in growth.

This has been the result of a series of factors, among which are the end of the BCE’s quantitative easing program, the slowdown in exports, which had recently boosted GDP growth, on account of Trump’s trade wars, and the structural lack of investments over the past few years.

Nonetheless, the idea of this “income”—as repeatedly explained by Pasquale Tridico, an advisor to Di Maio and a candidate to fill the role of Minister of Labor if there is ever a proper Five Star government—seems to be tied to these economic unknowables. According to Tridico, in just a short time, the person in “absolute poverty” will start buying “Italian products,” will get employed (in a permanent position, Tridico seems to imagine—not in small temporary jobs, as is most likely), and will contribute to the “wealth of the nation.” This is a completely naive view of the economic cycle, disregarding the actually recorded trends.

Not to mention what is the most blatant leap in the dark of the whole scheme: betting everything on the public unemployment offices, to be “reformed” in some yet unspecified way, in a country where 82 percent of job seekers turn to friends and family to find work. If this vision is ever put into practice at all, its implementation might be ready sometime in the next five or ten years, not in the next three months. To believe such an outlandish proposal, or even to mention something like this as a realistic hypothesis, is a clear sign that we are dealing with mere propaganda, not with serious plans as they claim.

The many problems of the M5S proposal, however, should not divert our attention from the political fight that has been waged over the past five years, a confrontation which has naturally intensified during the election campaign ahead of the March 4 elections. Everyone remembers the Democratic Party fighting against the proposal that has been (grossly misleadingly) called a “universal income.” Disingenuously pretending to believe the dishonest characterization of their own proposal by the Five Stars themselves, Renzi and his followers have spent at least four years attacking the very principle of an income that would be provided to all without asking them to do any work in return.

All this while they were all well aware—first and foremost former Economy Minister Padoan (“it would cost a lot, and, most importantly, it would perform poorly, because it would introduce negative incentives, so that people won’t go to work”—on OttoeMezzo, on Feb. 6, 2018)—that what the M5S was actually proposing was not a universal income at all, but a significant extension of the “social inclusion income” (REI), a flagship proposal of the Democratic Party, approved during the 2013-2018 legislature.

The difference was merely in the amount of money (about €10 billion for the current proposal—also adding the funds from the previous program—compared to €2.5 billion per year) that the quarreling politicians were willing to pour into what is essentially a forced labor machine. It is indeed a big difference in funding, but it should be emphasized that the “income” envisaged by the M5S is no different from what has already been passed by the Democratic Party. Both ideologically and technically, it is in perfect continuity.

We can look at some actual data, setting aside all the populist sound and fury. For example, Emilia-Romagna, a region governed by the Democratic Party, has approved the “solidarity income” (RES). Over four and a half months, 11,000 applications were submitted, averaging 93 per day. The RES is a benefit of €400 per month aimed at those in dire poverty living in households of up to five members. The system is the same as for the REI at the national level; however, there is one crucial difference: the region has decided to eliminate one of the most unfair requirements of the REI, and extended the RES benefit to families without children, to temporary workers and to those employed with low and very low income, the so-called “working poor.” This change, ultimately not a major one, managed to get 2,000 more households to apply: 69 percent of these applicants had no dependent children, so most are likely to be young and cohabiting.

A similar profile can be seen in the case of precarious workers, excluded from the REI, which was conceived as a measure that divides the poor arbitrarily and creates even more widespread welfare dependency in the end. The REI lasts for a maximum of one year, a time during which every one of the “poor” is assumed to have found (as if by magic) a job that allows them to be self-sufficient. Such nonsensical assumptions are common both to the Five Stars and to the Democrats, who like to present themselves as “serious people.”

A universal income is truly needed—this fact is absolutely clear. The problem is how it is enacted, as well as the dominant culture—which the quarreling politicians all share—which does not allow, and unfortunately will not allow, adopting a form of it that would be even minimally up to the requirements of the very serious situation we are in. The figures from Emilia are proof of the social drama playing out even among people living in a region that is theoretically a “developed” one. One can only imagine the situation in Calabria, Sicily or Campania.

The parties know all about this situation, as do all those who work on labor and social policy. Unfortunately, to date there is no possibility that the “growth” that Mario Draghi and his ilk are so obsessed with could trickle down to reach this vast, impoverished mass of workers and the unemployed. Everyone knows this, but everyone pretends that growth will be a remedy all by itself. And all the while, it is clear that the only thing reliably growing is the share of jobs that are precarious and extremely so.

This so-called “citizenship income,” and other schemes such as the French “universal working income,” are marred by the tension between giving people the possibility to choose how they live their own life and an authoritarian discourse of penalties and obligations. Welfarism clashes with dirigism: one is not allowed to sit on the couch all day, nor to take any break between unpaid community work and a training course.

You have to be working all the time. Keep running the rat race, don’t ever stop, and you’ll get a little cash in return. Better than nothing, right?

No.

This “compassionate capitalism” is authoritarianism that leads to pauperism. It is a synthesis of the right to social security and the ever-present duty to work. This project shows clearly the present tendency to demand a lot from those who have little in order to justify granting them a benefit of last resort that will not work towards overcoming poverty, but towards making the regime of full precarious employment a reality.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/la-truffa-linguistica-del-reddito-di-cittadinanza/ on 2018-10-20