Review

The Italianness of Latin America during fascism

Valerio Giannattasio’s new book, ‘Fascism in search of the New World,’ explores the foreign politics of fascist Italy, Italian emigration and the history of Latin America.

What image did fascist Italy have (and construct) of Latin America? What was its place in Italy’s foreign policy at the time, and what strategies were put in place in connection with the Italian immigrant communities in the South American continent?

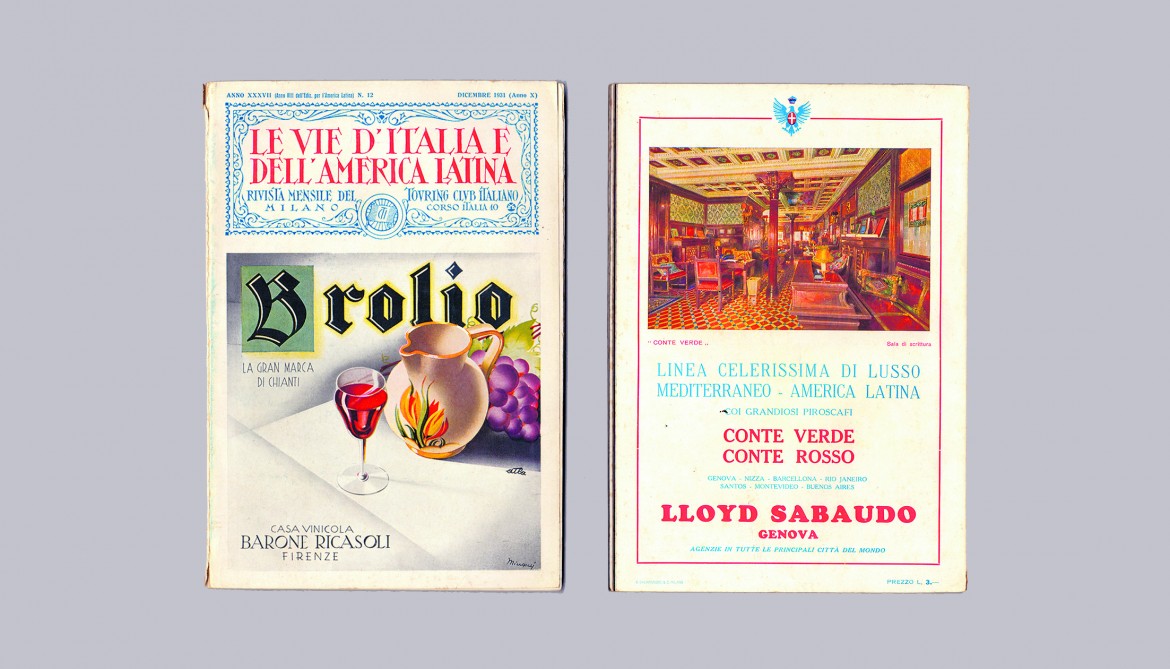

These are the questions that motivated Valerio Giannattasio’s research for his book Il fascismo alla ricerca del Nuovo Mondo. L’America Latina nella pubblicistica italiana, 1922-1943 (“Fascism in search of the New World: The Italian journalism in Latin America, 1922-1943,” ed. Ombre Corte, 233 pages, €22), which tries to answer them through an analysis of the contemporary travel literature, the articles published in magazines tied to the regime and those published ad hoc (e.g. Colombo), including also the monthly publication of the Touring Club, Le vie dell’Italia e dell’America Latina (“The Streets of Italy and Latin America”), which was first published in 1924.

In the first chapter, Giannattasio examines the image of the continent in contemporary publications, with its geographic, ethnic, social and economic features—an image that was particularly influenced by the issue of possible trade relations. In the second chapter, the topic is the relationship that the regime tried to establish with the Italians who had emigrated, which, in the government lexicon, changed from emigrati (“emigrees”) to italiani all’estero (“Italians abroad”—who numbered over 14 million from 1850 to 1930 in various Latin American countries), aiming to expand the economic and cultural influence of Italy, in the direction of the proposals articulated earlier by Crispi and then by the nationalist movement of the early 20th century. In order to work to the government’s advantage, reports on Italian communities abroad had to rely on the sentiment of “Italianness” that the regime attempted to revive through the spread of Fascism.

Since the end of the ‘20s, this project called for a convergence in the efforts of the diplomatic corps, the Fasci abroad, mass fascist organizations, government agencies, and cultural institutions such as the Dante Alighieri Society and, later on, the National Recreation Club (Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro). All these efforts—the book reveals—had little success, primarily because the sentiment of Italianness of the Italians who had emigrated the earliest had gradually disappeared over time, as the most acute observers at the time did not fail to note.

Then, the Italian regime’s project had to contend with the contemporary waves of Argentinian, Mexican, Chilean and Brazilian nationalism. This lack of success was in spite of the great propaganda efforts made by the regime: for instance, in 1924 with the cruise of the Regia Nave Italia, which circumnavigated the subcontinent, landing in 28 ports in 12 different countries, and in 1927 with a series of flights over South America that aroused plenty of enthusiasm.

The third chapter focuses primarily on the attention that Italian journalism at the time afforded the South American regimes that were imitating, in various ways and to various extents, the Mussolini regime: General Uriburo in Argentina, Vargas in Brazil, Alessandri and General Ibáñez in Chile. This interest—Giannattasio observes—did not translate into any “studies that would analyze in comprehensive form either the political movements taking place, the institutional implications or the popular mobilizations, or the growing participation of the citizenry.”

Then, the book examines the literature—particularly after 1929—that attacked Panamericanism, the expression of the Monroe doctrine and US imperialism. Against the hegemonic ambitions of the US, fascist writers proposed a doctrine of Panlatinism—the idea that the ties of solidarity between the South American nations were to be founded on their common Latin origin (i.e. on the “Romanness” of which fascism claimed to be the heir).

It is surprising that in these contemporary writings no references are found (or, at least, the book’s author did not deem them notable enough to mention) to Arielism—the intellectual movement which took its name from the essay Ariel (1900) by the Uruguayan writer Jose Enrique Rodo and argued for an opposition between Anglo-Saxon utilitarianism and materialism and the values of Greek-Latin culture. The fact remains that this cultural project also failed to have the desired results, on account of both the much higher penetration power of the United States in economic terms, and the outbreak of World War II.

An interdisciplinary work involving different research areas (the culture and foreign politics of the fascist period, Italian emigration history and Latin American history), Giannattasio’s work makes many other important points than can be mentioned here, but which testify to the usefulness and high quality of his research.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/litalianita-dellamerica-latina/ on 2018-09-26