Commentary

The assault on the Italian Constitution began in 1994

Berlusconi divided the country when he was alive, and he will continue to do so when dead.

Death commands a respectful attitude – of this there can be no question. Nor can there be any question about the significance of Berlusconi’s impact on Italy’s history. But he divided the country when he was alive, and he will continue to do so when dead. Even now, a part of the Italian people dissents from the seven days of parliamentary mourning and the day of national mourning – because they believe Berlusconi has been a significant cause of the country’s institutional and political weakening.

Berlusconi decided to run for Prime Minister in 1993. Not before, and there was no precedent for this before him, because political parties, with solid structures and deep territorial roots, had until then imposed an equivalent of the Roman cursus honorum that prevented the business tycoons of the day from having access to the upper echelons of politics. The collapse of the parties in those two terrible years – 1992 and 1993 – and the resulting vacuum were necessary conditions to make Berlusconi possible.

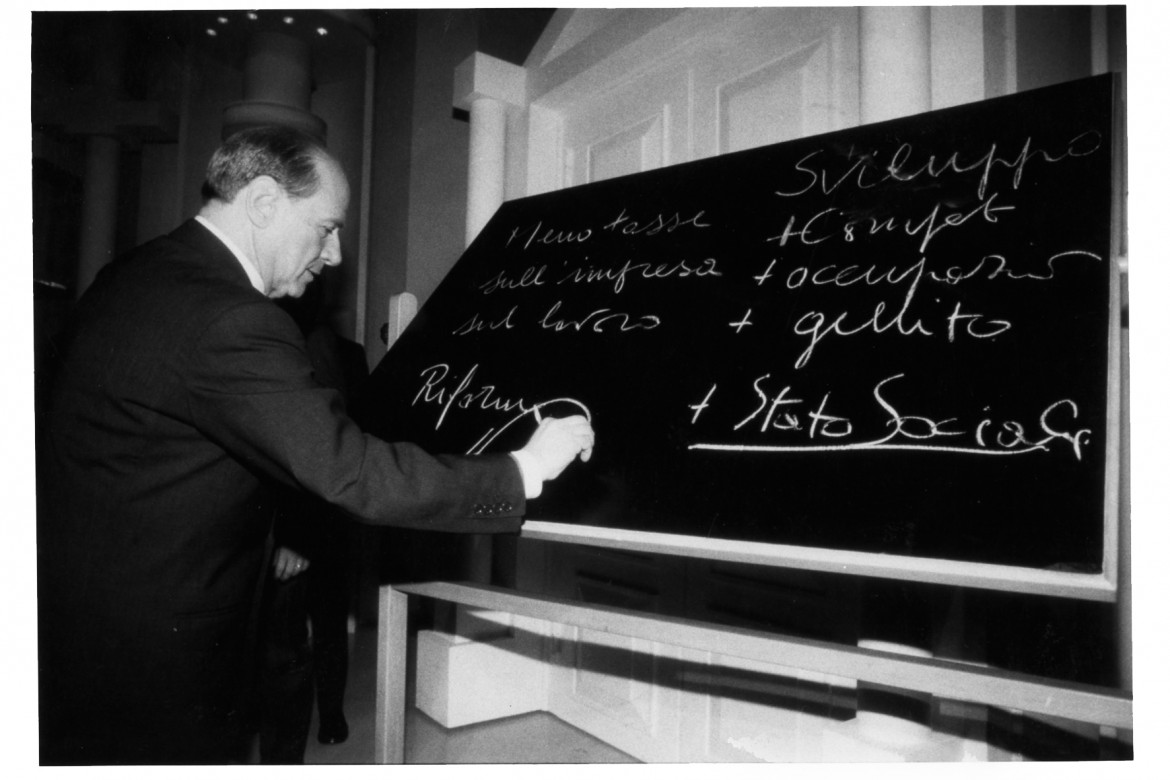

In the second half of 1993, anticipation was artfully manufactured across the country on the topic of “will he run or won’t he.” Finally, on January 26, 1994, TV stations showed his video ad: “Italy is the country I love.” Political professionals could not adapt to the change of gears in communication. Similarly, they failed to understand that the “artificial” party Berlusconi was creating was a real danger.

***

Berlusconi performed the political miracle of holding together Forza Italia, Alleanza Nazionale (heir of the MSI) and the Lega Nord. The victory of the center-right in 1994 broke the “constitutional arc” of the rule of the parties that had created the 1948 Constitution and provided essential support for it. Thus began a structural weakening of the Constitution, which has never recovered since.

Berlusconi’s interpretation of the meaning of the popular vote had a big part in this. On May 16, 1994, in his confidence speech, Berlusconi said that his electoral alliance had been “transformed into a government coalition on the explicit mandate of the citizens … I believe that this majority and this legislature must coincide, and that to constitute a new majority, new elections would be politically necessary.”

This is a break with the parliamentary form of government. In this interpretation, the roles of the President and Parliament are to rubber-stamp decisions that are basically dictated to them by the popular vote; and they would even be somehow subversive if they failed to heed it. When his government fell, Berlusconi put out a TV ad on December 19, 1994 in which he urged his supporters to go into the streets on his behalf, the sole and legitimate Prime Minister. Fortunately, the country did not heed this incitement. But the refrain of the “betrayal of the voters” stuck. La Loggia said the same on February 1, 1995 in the Senate, namely that the vote of March 27, 1994 had supposedly reduced the powers of the President of the Republic from “almost absolute” “to almost zero.” Thus was the Eden of politics irretrievably spoiled with the “commandment” that the popular vote must choose who should govern, and the “original sin” of overturning that popular will.

***

It’s no wonder that the right took this position. But one must wonder at the fact that similar ideas then came from Prodi in 1996, D’Alema in 1998, Amato in 2000, and again from Prodi in 2006 and 2008, at the moment of political defeat. And so it was that on May 13, 2008, in the Chamber of Deputies, Berlusconi, celebrating his victory, thanked the voters who accepted this view of things by clearly choosing a majority and opposition, and thus accepting “our joint appeal (from both his Pdl and the PD – n.ed.) to make the government of the country more clear, more efficient and controllable … This has been the first great reform.”

And Veltroni, head of the newly-formed Democratic Party, clamorously defeated after running almost alone, boasted that, by this joint “appeal,” he had introduced discontinuity from “the extreme political fragmentation and … constant demonization of the opponent” of the past. According to him, the PD had “the courage to make difficult and innovative choices.” Little did it matter that the collateral effect was delivering Parliament into the hands of the right.

An epitaph – to the political and cultural surrender of a left which, during the decades of Berlusconi, was unable or unwilling to defend its historical bulwarks of institutional and political culture, such as representation, the role of elective assemblies and intermediate bodies, the centrality of the principle of equality, of rights, of social cohesion.

***

It was, in the end, the Italian people who denied Berlusconian thinking a conclusive victory, by rejecting the center-right’s constitutional reform in the 2006 referendum, and Renzi’s reform in 2016. We don’t know if they would do it again. What we do know is that by playing catch-up with Berlusconi without the strength to propose a real alternative, the left has lost its soul. And, in turn, the country has lost its left.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/1994-lassalto-alla-costituzione-inizia-da-qui on 2023-06-14