Analysis

Russia's interest in Syria doesn't mean it welcomes refugees

Moscow is willing to go to war. It’s less willing to offer humanitarian support.

This article originally appeared in Latterly, a magazine dedicated to social justice reporting globally.

In early September 2015, President Vladimir Putin told a gathering of Russian journalists in Vladivostok that the migrant crisis in Europe was “absolutely expected.” He quickly attributed it to Western intervention in the Middle East and North Africa.

“We in Russia … in particular said a few years ago that there will be large-scale problems if our so-called Western partners pursue that incorrect — as I’ve always said — policy, particularly foreign policy, in the regions of the Muslim world, in the Near East and North Africa, which they have pursued so far,” Putin said.

“What is that policy? It’s the imposition of their standards, not taking into consideration the historical, religious, national, cultural characteristics of these regions. It is, before all else, the policy of our American partners.”

Later that month, Russia launched its own heavy-handed campaign in Syria in a display of force — and resultant criticism and controversy — that has only intensified since. And though the Kremlin has clearly demonstrated its commitment to ensuring its own interests are protected in Syria, including through its staunch support of President Bashar al-Assad, at the same time it has quietly avoided addressing the humanitarian crisis its intervention has worsened.

‘An unattractive country’

Russia may not be the first country that comes to mind for Syrians fleeing abroad. Halawa Faiz, a representative of a Syrian diaspora organization in Russia, said as much to media outlet RBC this week, noting that its weather, expensiveness and problematic transportation to the European Union do not make it “an attractive country for Syrians.” Yet Moscow’s close ties to Damascus date back to the Soviet era, long before its siding with the Assad government in the ongoing civil war.

Thousands of Syrians, including members of the elite, once studied in the Soviet Union. Assad’s father, Hafez, received fighter jet training there in the late 1950s, later returning after his successful coup in 1970 to ask for Moscow’s continued support. Syria permitted the USSR to use the port of Tartus as a naval base in 1971, cementing the country’s role as a key Soviet outpost in the Mediterranean. Many Syrians married Soviet citizens; a large number returned to Syria, bringing their mixed families with them. By 2012, some 30,000 Russian citizens were living in Syria.

Yet for Syrians seeking refuge in Russia today, their welcome is not as warm as the decades-long relationship between the two countries would suggest. Though Russia is a party to the U.N.’s 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol, and has its own domestic legislation on refugees, the official response to Syrian refugees in the country ranges from arbitrary to indifferent.

Svetlana Gannushkina, an immigrant rights activist and the chair of the Moscow-based Civic Assistance Committee, told The Moscow Times that although there are likely 100,000 people in Russia who should be eligible for official refugee status, a minuscule fraction actually receive it. “It is difficult to wrap one’s head around the fact that there are just 770 official refugees living in Russia,” she said. Seven hundred seventy in a country of over 142 million people.

Little sympathy

The Committee reported that 2,011 Syrian nationals requested refugee status in Russia between 2011 and 2015, with only one receiving it in that period. The odds of securing temporary asylum were better: 3,306 out of 4,462 applicants — 74 percent — were granted status for one year. This interim status, however, cannot be renewed, merely postponing the problem. According to figures at the end of 2015 from the now-defunct Federal Migration Service (FMS) — which was absorbed into the Interior Ministry on April 5 and stopped publishing statistics — 1,032 Syrian citizens had received temporary asylum, and only two had secured refugee status.

The Committee’s report detailed that refugees are left unprotected as they wait for their asylum proceedings. If they lack a Russian visa, they are in the country illegally and are at the mercy of police officers and the court system. Refugees may be robbed during a routine documents check, or worse, arrested and brought to court, where they face fines, detention for up to two years or even expulsion from the country. Migration authorities and officials, the report notes, often lack proper translation services, with translators even inaccurately translating for the refugee, giving them bad advice or recommending they pay bribes.

Furthermore, as the report illustrates, the situation for Syrian asylum-seekers has deteriorated in 2016. The Committee recorded that out of 82 decisions by migration authorities in the first half of 2016, 57 were refusals to grant temporary asylum and 17 were refusals to extend it. Refugees were given temporary asylum in only seven cases during that period, and only one had their status extended.

Women and children received the same treatment as men. In one particularly striking FMS decision in March, a pregnant Syrian refugee was denied temporary asylum on the grounds that she “did not cite evidence that her risk of becoming a victim of persecution [in Syria] was higher than the rest of the population of Syria. Practically the entire population of the country is experiencing day-to-day difficulties. The reluctance of residents of Syria to return to the country is the reasonable outcome of the poor economic and humanitarian situation in [their] homeland.” Notably, the author of this ruling was a woman.

Charity or ‘foreign agent’?

But the bureaucracy isn’t the only explanation for the difficult environment confronting Syrians in Russia, however. In addition to the Civic Assistance Committee, other NGOs, including Amnesty International, Oxfam International and Human Rights Watch, have documented the Russian government’s inadequate response to the Syrian refugee crisis both abroad and in Russia and its impact on the treatment of Syrians who arrive there.

In its “fair share analysis” in February, for instance, Oxfam reported that Russia had contributed $6.9 million in funding for the Syria crisis response in 2015 — 1 percent of its calculated fair share, and the least of the 32 countries in its analysis. Based on the size of the Russian economy, Oxfam found its fair share for resettlement and humanitarian admission pledges in 2016 would be 33,356 refugees. But Russia had pledged zero places for refugees at the time of the report. Human Rights Watch later highlightedthat Russia was conspicuously absent from the 45-country “Supporting Syria and the Region” conference in London in February, which raised $6.1 billion in funding for 2016 and $6.1 billion in funding for 2017–2020.

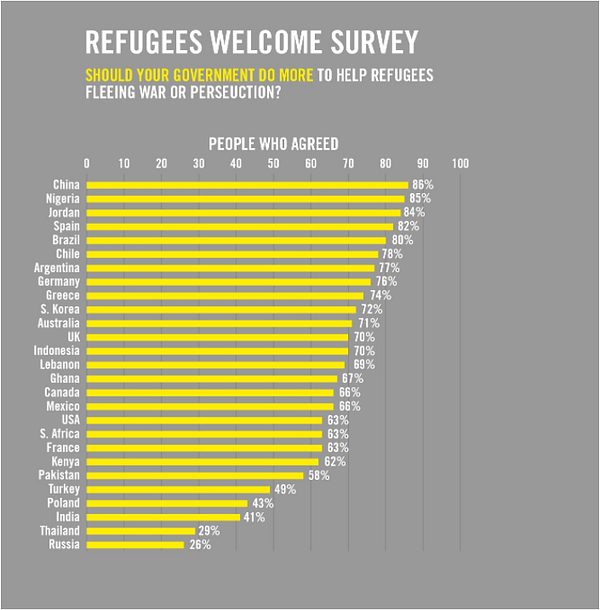

In May, Amnesty International released the results of its first-ever Refugees Welcome Index. Russia was ranked as the least-welcoming country on the list. Only 26 percent of Russians surveyed thought their government should do more to help refugees fleeing war or persecution, the lowest percentage of public support for a more robust response. Amnesty reported that only 17 percent of respondents worldwide stated they would refuse refugees entry to their countries. But Russia was the one country where more than one-third of respondents — 61 percent, in fact — said they would deny refugees entry.

The Syrians arriving in Russia in the last few years are the latest in a series of waves of refugees — all of which have experienced trouble integrating into Russian society, according to the Civic Assistance Committee’s Gannushkina. For Russians, the word “refugee” may not immediately conjure an image of the Syrians fleeing civil war through Turkey or the E.U., or the Africans and others attempting the deadly Mediterranean crossing to Sicily, but instead an experience closer to home, even personal. Over 1 million Ukrainian refugees, largely Russian-speaking, have fled the war in eastern Ukraine for Russia since 2014. These refugees joined the millions of others who had fled ethnic conflicts, instability or economic hardship in the former Soviet republics for Russia since the USSR’s collapse in 1991. Meanwhile, the number of Russian citizens seeking asylum themselves in the U.S. and E.U. has shown a marked increase in recent years.

Yet the NGOs and charities that help refugees, including Syrians, in Russia face government scrutiny of their own. A restrictive 2012 law mandates that all independent organizations that receive any foreign funding or support and engage in ambiguously defined “political activity” must register with the Justice Ministry as “foreign agents,” a label that characterizes them as implicitly un-Russian and has chilling Soviet-era connotations. Hundreds of organizations have been classified as “foreign agents” since. (The Committee for Civic Assistance has been one since April 20, 2015.) And in November, Amnesty International’s Moscow staff arrived at their office to discover that the city government had shuttered the space with no prior warning.

Adding to the challenges for Syrian refugees in Russia is the discrimination and suspicion many people with non-Slavic appearances face, including in housing and treatment by the police — even in large cities like Moscow and St. Petersburg. As an American living in Moscow in the summer of 2011, I was told to carry my dokumenty, including my passport, visa and registration, with me at all times in case I was ever questioned by the police. Several times that summer, I watched as an unfortunate passerby was stopped and surrounded by police officers, their documents scrutinized and possessions rifled through. Yet with my own Slavic-looking features and Russian fluency, I was assumed to be just another Muscovite on the street.

Someone else’s problem

Russia’s troubled track record of accommodating and integrating refugees, even from within its own borders, is unlikely to improve for the Syrians in the country today. The government’s loosening or expediting asylum procedures, or allowing larger numbers of Syrians to stay in Russia permanently, would amount to a tacit admission by the Kremlin that the situation on the ground in Syria — and by extension, the assuredness of its strategy in the country — are not as they seem.

Perhaps, as Putin expressed in his criticism of Western intervention last year, the Kremlin believes it can simply continue to handle security matters, while the West can rectify the problem its own mistaken policies have created. “Russia claims that it has made a huge contribution to combating terrorism, but its actions make it clear that others should deal with the refugee problem,” said Tatyana Lokshina, Human Rights Watch’s Russia program director, to RBC last week.

The actual stories of Syrian refugees in Russia, and the NGOs that assist them, contradict this official narrative. Ultimately, their experiences illustrate that though Syria plays a strategic role in the Kremlin’s geopolitical calculus and foreign policy aims, the suffering of many Syrians themselves is less pressing for Moscow.

Originally published at on