Reportage

Remember this name and why he died: Zülküf Gezen

Thousands of Kurdish prisoners are participating in a hunger strike to end the solitary confinement of PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan. Nine people have already taken their own lives as acts of protest. The family of the first, Zülküf Gezen, asks only that the memory of his suicide not fade.

In the days following the March 31 Turkish administrative elections in Diyarbakir, in spite of the victory of the pro-Kurdish HDP party, there were no official manifestations of celebration, and life in the cities went on exactly as before.

It was as if nothing had happened, even though the election results in the region represented a resounding defeat for the AKP, the ruling party of President Erdogan, who is governing the country with increasingly repressive measures against ordinary citizens and democracy, and who is also responsible for a growing economic crisis that is having severe effects on the country and is adding to the numbers of families in need.

But the business-as-usual atmosphere is just a facade. Behind the semblance of normality, rumors are swirling and there are plenty of portentous omens of bad things to come: a few days after the vote, the Ankara government decided to contest the election of newly elected mayors across Diyarbakir, a region in the heart of Turkish Kurdistan—a sign of a possible return of the government’s active campaign of persecution against this Kurdish-majority district, and not only.

In November 2018, as part of a continuing political conflict that has led to the government imprisoning over 10,000 members and supporters of the HDP, political prisoners began a mass hunger strike, which quickly spread, coming to involve around 7,000 participants. The protest took off thanks to the courage of Leyla Güven, an HDP deputy arrested in January 2018 for criticizing the Turkish “Olive Branch” military operation against the Kurdish canton of Afrin in northern Syria, in which Turkish troops invaded the district and harassed the civilian population.

With the slogan “Leyla Güven’s demand is our demand,” the strike spread like wildfire outside the jails, reaching many European nations and even the United States, where there are currently around 250 hunger strikers. There are also some in Italy, since March 21, the day of Newroz, the Kurdish New Year.

The primary goal of this indefinite hunger strike—for which the participants are ready to give their lives—is to get Abdullah Ocalan out of solitary confinement. Ocalan is the leader of the PKK, whom they consider their political voice and believe to be the one man who could bring about a peaceful solution in the conflict between Turkey and the Kurdish people. Since 2011, Ocalan has not been allowed any legal assistance, and since 2016 he has only been allowed one visit, from his brother, which lasted just a few minutes.

This kind of struggle, silent and fraught with the physical ailments that come with abstaining from food—which becomes life-threatening after the 50th day—is not new among the forms of protest chosen by Kurdish political prisoners. However, while a hunger strike is the only lawful method of protest that can be used in prison, it has also inspired even more tragic forms of protest: since March 16, eight prisoners and a Kurdish man living in Germany have taken their own lives, intending to give more weight to the protest and launch an even sterner warning for Western political society, which—unexpectedly, but not surprisingly—has been keeping an almost-unbroken silence about what is happening.

The blame for this attitude can be placed mainly on the European institutions, to which the Kurdish people have appealed several times to come to the defense of human rights—and the many levels of the relationships between these institutions and the Turkish government have certainly played a role. The silence of the European Union means that it will bear a heavy share of the responsibility for the fate of the strikers, as the lives of many of them are already hanging by a thread.

The first of the protesters who committed suicide was Zülküf Gezen, a 28-year-old man from Diyarbakir. He was followed by Ayten Becet, Medya Cinar, Yonca Akici, Ugur Sakar, Siraç Yuksek, Ümit Acar, Zehra Saglam, and, the latest, Mahsum Pamay, just 22 years old.

It’s raining in Diyarbakir, the traffic is heavy, and our bus is slow and crowded as it heads for one of the new neighborhoods at the outskirts of the city, a token of the recent urban expansion, with hundreds of newly built apartment blocks, all the same. Zülküf’s family has agreed to a visit from us, so they could tell the story of their son—the middle one of their three boys—who was the first to resolutely follow through with his decision to end his life in protest.

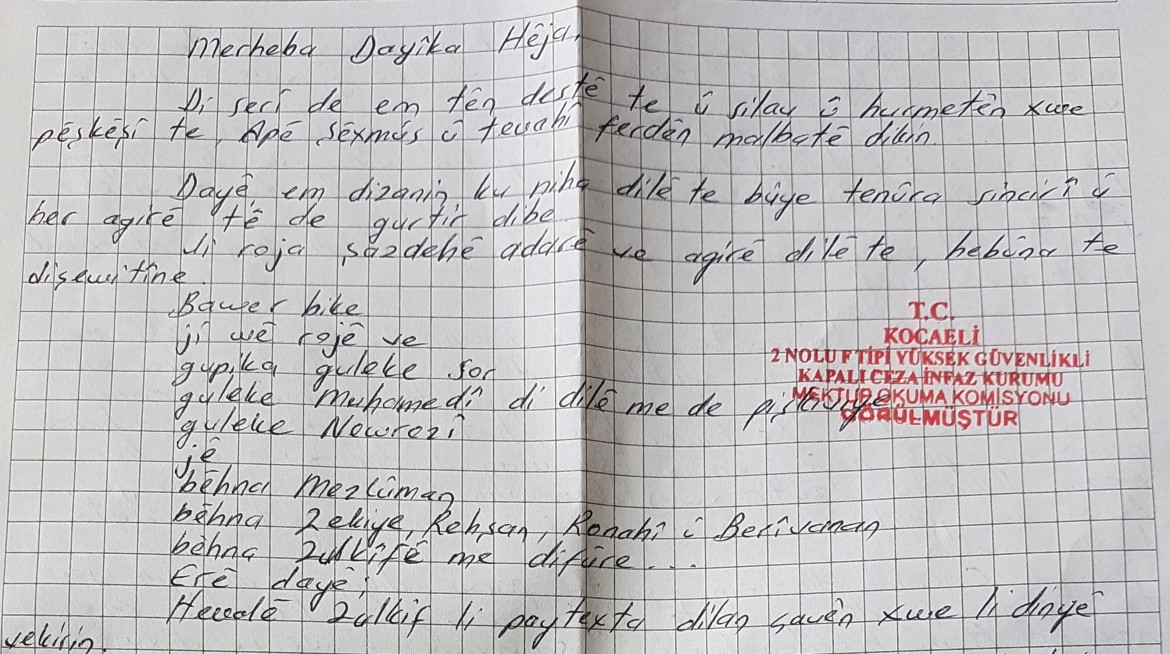

For his mother, who wears a pure white veil, it is all too much to bear—one can see it in her eyes. Still, she tells us that she is proud of her child, who wasn’t afraid to face death for the cause he believed in. Over tea—an obligatory custom here—Zülküf’s family shows us photos of him at earlier ages: he was a child born in the midst of what can be fairly described as a civil war.

His family isn’t asking for justice, just that his untimely death—along with the other eight who have died in the same way—not be forgotten, that the memory be preserved of a gesture that at the very least might awaken the consciences of governments and urge all those who believe in a better world to fight against authoritarianism and human rights violations—both those directed against the Kurdish resistance and all others everywhere.

Justice is not something that Zülküf’s family is used to getting. They never even mention the word, and probably it’s not even something they think about. Perhaps that is why the only message they wanted us to deliver was to preserve the memory of their son and the other young lives lost in the solitary confinement cells of Turkish prisons. It is a memory of something that simply doesn’t happen in the life of us Westerners—but, for those who have ears to hear, it is a message that speaks to all of us, loud and clear.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/zulkuf-e-gli-altri-morire-in-cella-per-non-essere-piu-isolati/ on 2019-04-14