Commentary

Racism and inequality, the two threads of anger

What is happening today is more than just a desperate revolt. The uprising is now representative enough to be unable to be ignored, and big enough to surround the White House itself, forcing it into lockdown.

The uprising is universal: both violent and non-violent, involving African-Americans and many others, men and women. The protest is common, while the source of the anger is not the same for everyone. Because the two threads that are intertwining are, most importantly, anger at the recurring murders of African Americans and exasperation at a social situation that has collapsed dramatically in recent months.

Even the ways in which the victims are being murdered are always the same: suffocated on the ground, with one knee on their necks—George Floyd in Minneapolis in 2020 and Eric Garner in New York in 2014—or shot, like young Ahmaud Arbery who was having fun running in the street in Georgia in 2020 and little Tamir Rice who was playing in a park in Cleveland in 2014 (and Breonna Taylor at her home in Louisville, Kentucky, in 2020, or Michael Brown in a street in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014, and so many others).

If we were to try to include all the victims, the list would be unbearably long.

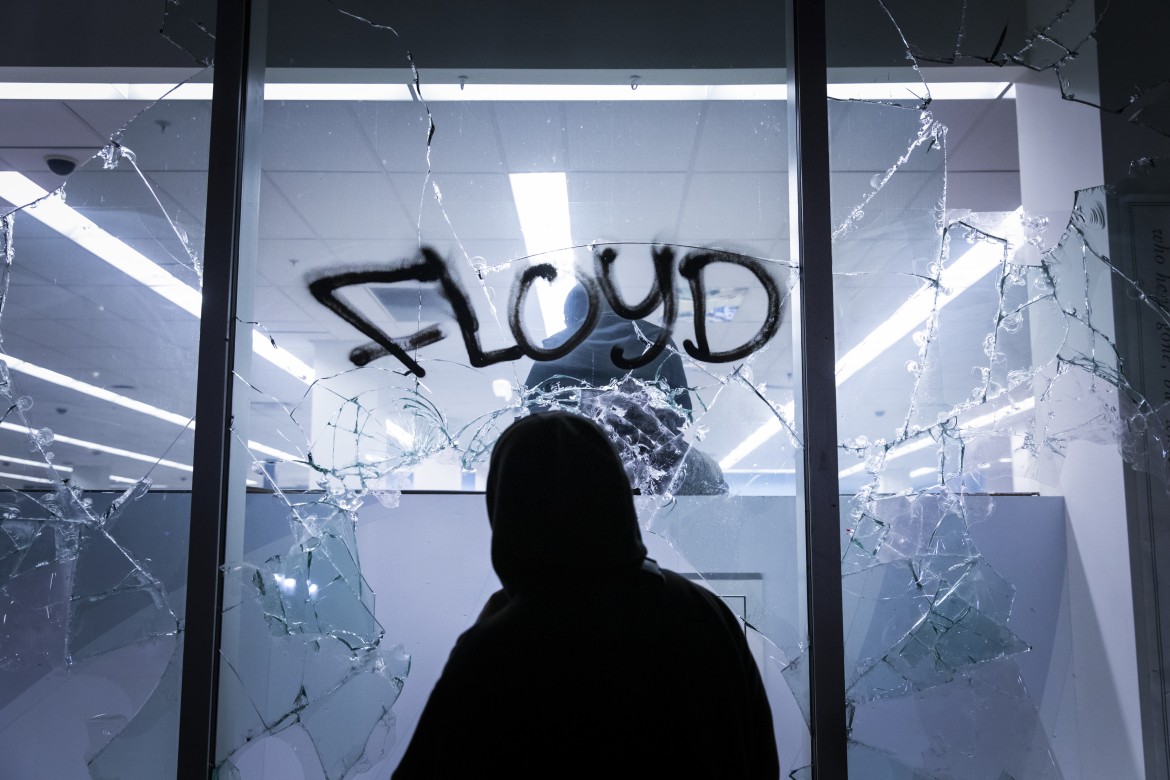

It is in response to the senseless repressive brutality that this most destructive revolt has broken out. “An eye for an eye” was written on one of the signs held in the light of the flames of one of the fires, as police stations were devastated and set ablaze, cars were set on fire, shops looted.

And then came the repression by militarized police forces, the National Guard and army personnel on high alert in Minneapolis, Detroit and elsewhere: “When the looting starts, the shooting starts,” tweeted Donald Trump with a full dose of brutal honesty (the same kind with which Ronald Reagan had called for a “bloodbath” against the popular movement of his time more than half a century ago).

What is happening today is more than just a desperate revolt—and not only because almost everywhere, in all cities, a complex network of political and largely non-violent solidarity has now formed around the protest. The uprising is now representative enough to be unable to be ignored (or reduced to mere “thugs,” in Trump’s words), and big enough to surround the White House itself, forcing it into lockdown. The growth of all the anti-Trump mobilizations of the previous three years has raised awareness on a social level, and is now infusing this display of solidarity with strength and conviction.

On the other hand, there is the second thread motivating the protests: from March until today, the dramatic growth in unemployment has hit the African American community particularly hard, the one most affected by the coronavirus.

Trump’s lack of interest in the threat of the pandemic, which persisted for a long time, despite the lessons that could have been learned from other countries, and his incoherent decisions and outbursts have had devastating effects.

All the surveys have shown that African Americans were the most affected by the outbreak (including in prisons, where they are the overwhelming majority), and to many of them it appeared clear that part of that disinterest was due to the fact that “anyway, it’s mostly ‘them’ who are dying, not us.”

Then, in April, there was the explosion in the number of layoffs, which in less than two months led to over 40 million people losing their jobs. Among them, the percentage of African Americans and Latinos, both men and women, was disproportionately high. Many of them have no savings available, and when they lost their jobs, they also lost the welfare coverage that came through their employers. They have suffered a twofold crisis.

Not all of the layoffs will be permanent, they say—and they’re probably right. When the recovery comes, some people will be hired back. However, many jobs—both new jobs and jobs that have not yet been eliminated—will be part-time and at lower wages than before.

Fast food workers, both men and women, are in danger of losing the wage gains they managed to secure after the struggles of recent years, such as the $15 hourly wage. The same is true for those working in sales, catering, construction, manufacturing and delivery, who had managed to win better working conditions, and in some cases unionization.

Those newly hired by hospitals and healthcare institutions—who were hailed in the United States, like everywhere else, as “the heroes of COVID-19”—are already starting to be sent home in the places where the contagion has subsided.

All these are the sectors with the highest African-American and Hispanic proportion of the workforce, and in which the wage and unionization struggles have been fought with the greatest determination (in recent months as well, they have given rise to prominent forms of resistance, particularly at healthcare institutions).

Moreover, black men have been the most unionized category of workers for decades, and black and Hispanic women have been the leading protagonists of workers’ demands in recent years. These were the first among workers to be fired, and with the least likelihood of being re-employed. But it is precisely the determination with which they have struggled in recent years that has now given many of them the motivation they needed to direct their anger, fueled by the combination of the unacceptability of yet another racist crime together with the unbearable social condition they find themselves in.

They are not the young people who are at the center of the protests and fires, but like in all resistance movements, they are the necessary rearguard to give the movement political weight, build coalitions and keep it moving in the right direction.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/razzismo-e-diseguaglianze-i-due-fili-della-rabbia/ on 2020-05-31