Commentary

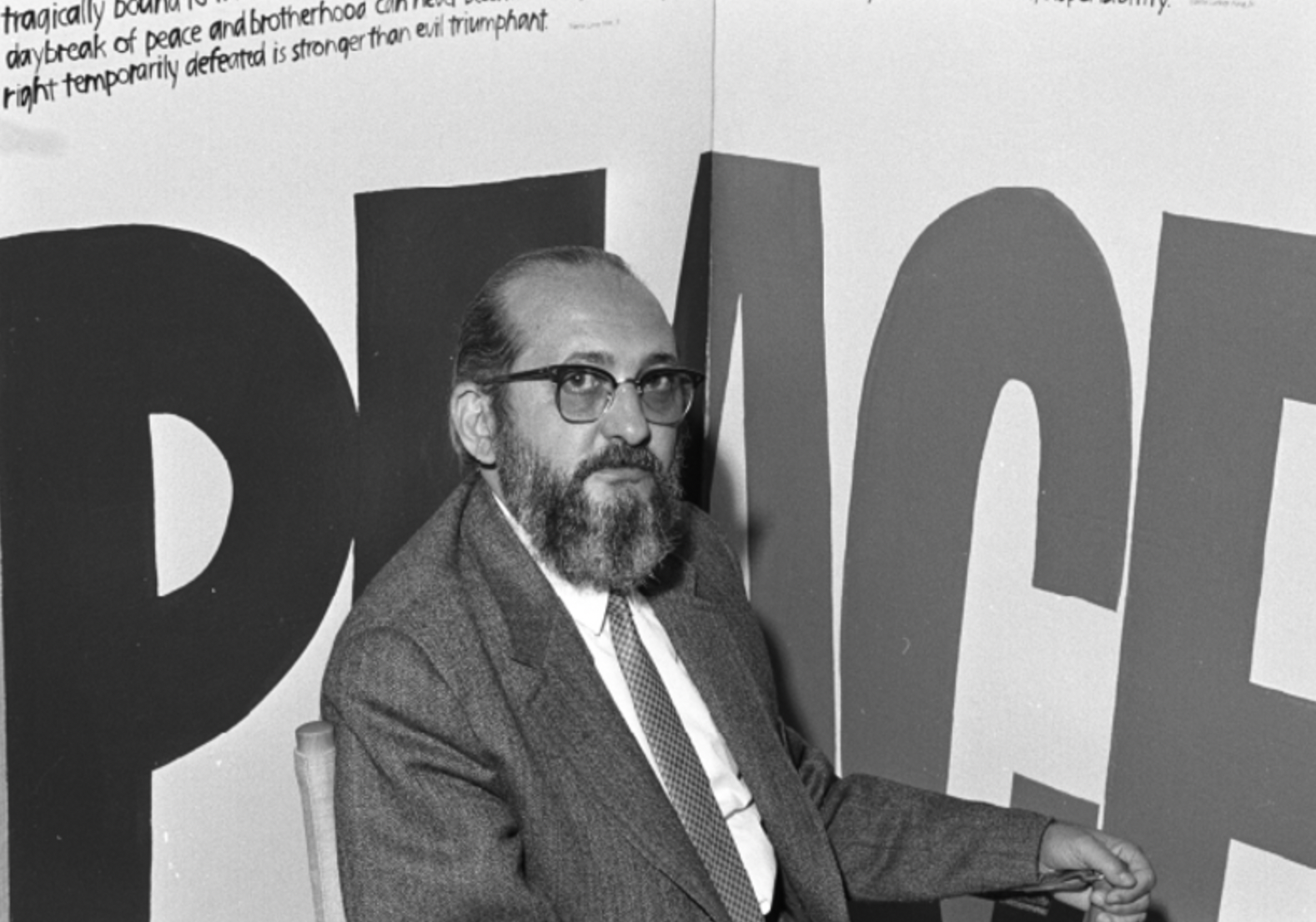

Paulo Freire at 100 still assures us the imperative of hope

One hundred years ago, the great Brazilian educator was born. He fought to expand his ‘pedagogy of the oppressed’ and was persecuted by the dictatorship. Even today, Bolsonaro insults his memory.

On the occasion of the 100-year anniversary of the birth of Paulo Freire (Recife, 1921 – São Paulo, 1997), in spite of the commemorative initiatives that have multiplied worldwide—or perhaps precisely because of them—the favorite sport of the Bolsonaro family seems to be insulting the memory of the Brazilian educator, trotting out terms such as “zealot” and, in an obviously derogatory sense, “idol of the left.”

In reality, the colorful expressions used by the former military officer are indicative of last-ditch efforts at reductionism, trying to look for a scapegoat with the intention of diverting attention from the outrageous series of disasters that his government has perpetrated. For no fault of his own, Freire is being set up as the cause of all “evils,” particularly those in the schools and universities.

On the one hand, ridiculing the public education sector is useful for opening up the field to the most unscrupulous forms of private initiative; on the other hand, calling a humble and deeply sensitive educator like Paulo Freire a zealot—energumeno, literally a madman, obsessed, even possessed—serves as a dog whistle for the significant number of groups—not quite moderate themselves—that are disturbingly attracted to witch hunt scenarios.

A few decades ago, Freire used an expression that could be fitting to describe the mentality that emerges from the narrative of his current accusers: the “naive conscience” that “shows a certain simplicity, tends towards a facile interpretation of problems, approaches issues with naivety, does not go deeper into the causality of the fact itself.” Moreover, he warned about how naive consciousness could degenerate into a massified or fanatical dimension, something we can currently find in the world of fake news, of sectarianism, of the power of falsehood exploited by the extreme right through speeches in which the tenuousness of the cause-effect relationship, and the consequent absence of understanding, is persuasive for those who do not have the will or intention to understand the phenomena in depth.

On the other hand, Paulo Freire’s call to the existential necessity, even the imperative, of hope, resonates much stronger than even the most earnest sentimental appeal and is still capable of striking fear: because hope is not a romantic attitude, but the concrete root of a method based on the denunciation of conditions of oppression and the consequent political organization aimed at overcoming them.

Such reflective and transformational action leads to interpretations of meaning, readings of the world, points of view hitherto unseen. Paulo Freire would not have been exiled by the military dictatorship if his method for literacy, inserted into a broader political-educational system, had not been a true generator of transformation in history: “Hope, as an ontological necessity, must be anchored in practice.”

It is no coincidence that in all the initiatives for the 100-year celebration (in Italy, those who took part were the Educational Cooperation Network, the Basso Foundation, Popoli in Arte, the Paulo Freire Institute, the Freire-Boal Network, Educazione Aperta, the Italian Society of Pedagogy), there is constant reference to the verb esperançar, which means the practice of hope, an action rather than desiring an outcome in itself. His thought can still strike fear, because it finds real correspondence in the experiences of the popular movements, both rural and urban, grassroots communities, peasant women and workers of both genders, who, in the context of undergoing a political process of popular education, are building something that’s not yet there, but can be created: the unprecedented possible.

At the same time, in the meetings, debates, and publications on the occasion of the centennial, the idea has forcefully emerged that re-encountering Freire does not only mean looking back to his time: “I don’t want to be followed, I want to be reinvented,” said the Brazilian educator. His experiences mark a concrete path of research and historical overcoming of a model that he himself called the “banking model” of education, which is not only still dominant, but has even strengthened with the advancement of capitalism. A system in which people are not accustomed to dialogue, ending up by losing the ability to ask questions, unwittingly finding themselves in a deep crisis generated by the passive acceptance of a reality impoverished by the lack of interest in other points of view.

Education is currently being described in terms of “credits” which are due and owed, terms which are very fitting for the financial system, but not so fitting for an educational context: schools and universities are defined as “training agencies”; words such as “efficiency,” “productivity,” “human resources” or “expendability” are being used in the everyday.

In the field of critical pedagogy, inspired by Freire’s thought, there is a growing determination to overcome the technocratic tendencies of educational models in order to open up pathways to a political and educational culture capable of going beyond capitalism, of unmasking its hidden and destructive sides.

It is understood that there is no hope outside of a political struggle that would create ways of life in clear opposition to the dominant system: agroecology, cooperative approaches to work, the fight against corporations and mafias, policies of welcoming and solidarity that are able to reinterpret the phenomenon of migration, permanent information networks, theater of the oppressed, ecofeminism.

These are all political realities and practices that go against the current, identifying their center of gravity in mobilization and political imagination, because “when there is no more room for utopia, for dreams, for choice, for decision, for waiting, all in the struggle—which happens only when there is hope—then there is no more room for education. Only for training.”

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/paulo-freire-un-alfabeto-di-speranza/ on 2021-09-19