Analysis

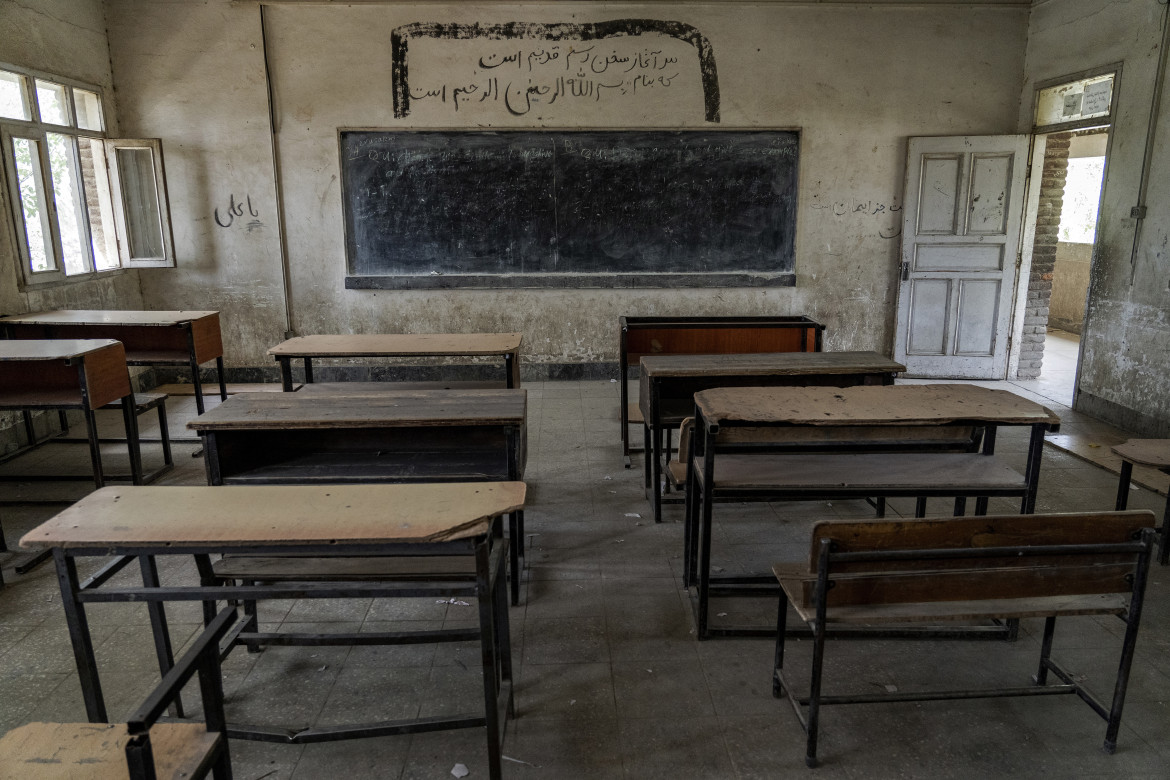

Open and shut: Afghan girls schools hostage to Taliban politics

On September 10, dozens and dozens of female students, wearing school uniforms, demonstrated in the streets of the provincial capital, Gardez, to demand reopening.

In recent days, in Paktia province, schools that had been closed for girls were reopened by local authorities, only to be closed again by central authorities in Kabul. It is a region that is not very central, in the eastern area bordering Pakistan, but the significance of the ongoing back-and-forth is crucial: it tells of the internal disagreements within the Taliban movement, now that they have moved from guerrilla warfare to running ministries, and it also tells of the social conflict in the country. A more underground conflict, compared to the military conflict with the resistance fronts and the local branch of the Islamic State, Khorasan Province, but far more important than those.

Let’s start with the events: about a week ago, government authorities in Paktia Province announced the reopening of five girls’ high schools in Gardez and Chamkani districts, after tribal councils and local authorities, under pressure from the local citizenry, had given the go-ahead for the reopening. In most of Afghanistan, girls’ high schools have been closed for more than a year, ever since the Taliban returned to power. “In the past few days, some schools have reopened and principals have invited female students to return to school.” This is how Khaliq Yar Ahmadzai, who heads Paktia’s Information and Culture Department, presented the news.

This news was not taken well in Kabul, which was never asked for permission. Thus, spokesmen for the Emirate were quick to say that any such decision must go through Kabul, despite the fact that some girls’ high schools continued to remain open during this time, such as in the northern province of Balkh. The Emirate followed up on its words: the schools were immediately closed again.

On September 10, dozens and dozens of female students, wearing school uniforms, demonstrated in the streets of the provincial capital, Gardez, to demand reopening. According to several sources, the Taliban reportedly arrested the parents of some female students and detained journalists who gave coverage of the demonstration for hours. This was followed on Tuesday by a statement from the Emirate’s de facto Minister of Education: “In our culture, no one wants to send their grown-up daughters to school.” This provoked a very strong reaction across the country, where the demand for education, and quality education, is actually widespread, and not only in the major cities.

The dispute reflects one of the main limitations of the Taliban: their inability to recognize how different Afghan society is from the one that they imagined during the many years of guerrilla and underground warfare, training of martyrs and suicide bombers.

But what is also emerging is internal dissent: the reopening of schools took place in Paktia, a traditional “fiefdom” of the Haqqanis. Responsible for killings and slaughter, among the Taliban they are, however, among those who are pushing hardest for reopening. Behind the reopened 5 schools was their attempt to force the others’ hand and put the southern, Kandahar-based group of political leaders in a bad position in front of Afghan society and international diplomacy.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/aperte-e-poi-richiuse-in-afghanistan-scuole-femminili-ostaggio-della-lotte-interne-ai-talebani on 2022-09-14