Remembrance

My Ali: How an American boxer championed sport and life

Muhammad Ali recognized the weight of his pulpit and used it to speak justice.

In 1967 Muhammad Ali spoke these verses during his speech on conscientious objection: “The draft is about white people sending black people to fight yellow people to protect the country they stole from the red people.”

Re-reading it today, this invention looks like an ante litteram rap restating the versatility of a character like him. Maybe this is why he was detested from the beginning and, in spite of this, he was never a loser.

I know that a eulogy to a sporting champion is something unusual, but like I wrote in the book My Ali I believe that only those who are not informed enough can discuss the homage to Muhammad Ali-Cassius Clay for what he meant, for what he represented, for what he said and for what he has done.

And in the era of television, where everyone gets a prize, this king of the ring, ready to expose himself to defend not only his rights, but also those of many other people, has represented an indisputable example.

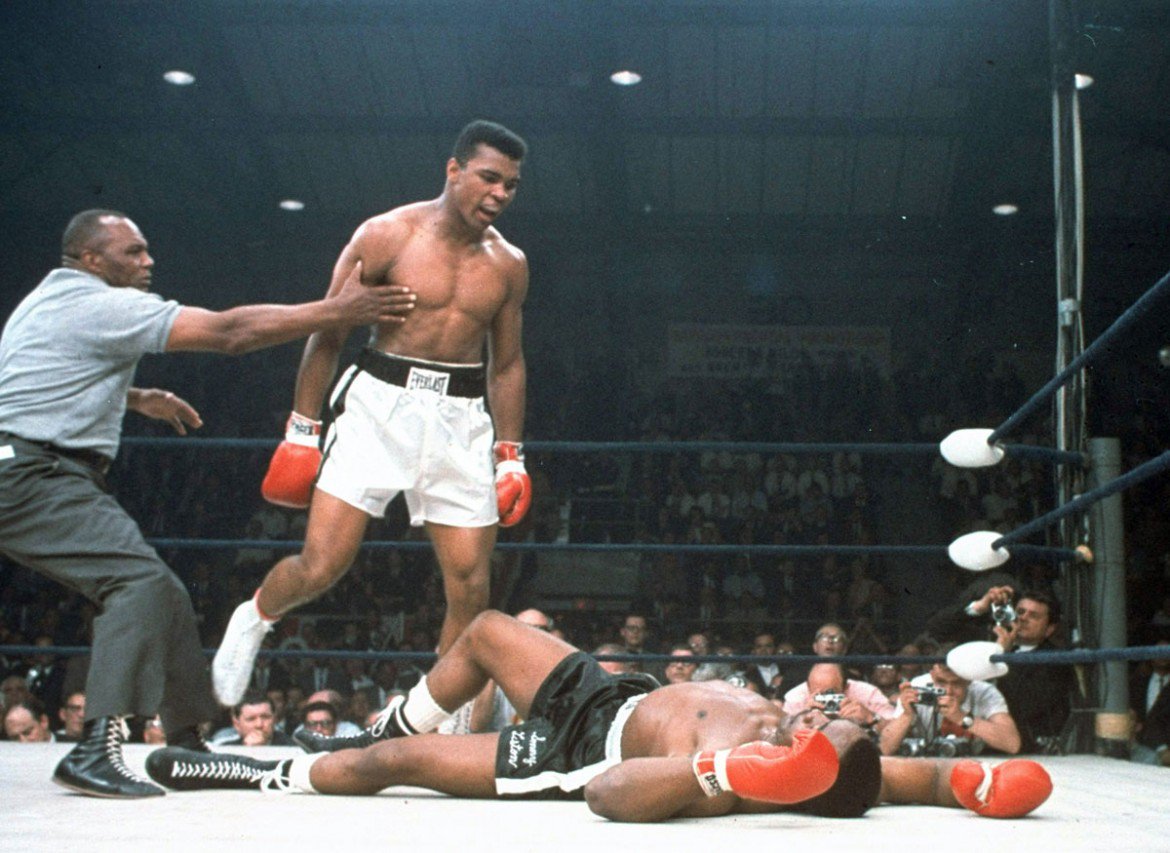

At 18, he won the gold medal in boxing at the Rome Olympics, middle-heavy class, surprising and pocking with punches Zbigniew Pietrzykowski, a Polish boxer who up to that moment had many Olympic and European victories. At 23, having become a professional, he conquered the heavyweight title by wiping out a tough guy like Sonny Liston.

Nonetheless, his excellence was to have been a great man before being a great boxer.

In fact, no other sportsman, or protagonist, in our time has been able to transcend the borders of his world like Muhammad Ali did in order to become a positive example, a person accepted by everyone, even by those who, in the ‘60s, despised him for pretending to be more than the champion he was, much more than that wonderful innovator in boxing, from which he took out the violence, and to which he gave, often, the movements of a dance, the joy of a party, almost in an artist’s style.

Then this young, beautiful and, apparently, superb youngster, who influenced his adversaries rather with mocking behavior than with the will to hurt them, wanting to give voice, taking advantage of his fame, to a people, millions of African-Americans who were still struggling to impose their own rights and still had to conquer a full emancipation in the United States.

Half a century after that, a black man with African roots, Barack Obama, is the president of that nation and the merit for this incredible social evolution belongs to people like this boy from Louisville, Kentucky who died Friday at 74 years old and, influenced by the African-American writer Malcolm X, changed his name to Muhammad Ali, converted to Islam, refused because of his religious convictions to fight in Vietnam and, for this, was deprived of the world championship title he would have won back only six years later against George Foreman, defeated by knock-out in Kinshasa, Congo, in what was called the “match of the century.”

Stories like his helped convince Congress to change the law on conscientious objection. In the meantime, to get to this match, Ali had to fight Joe Frazier, his constant adversary, and to defeat him two times out of three in epic matches that left scars on both fighters’ health.

Ali was a champion and an idealist. He once explained his public style to me as a dance of wills. “My ability as a boxer … would have been useless if I hadn’t understood that I had to use the media instead of being used. And, if I really wanted to show my discomfort, the protest, the pain, the pride of the African-American people, I had to use those microphones you were throwing in my face after victories. I had to spit my sentences, my exasperated challenges on your notepads trying to precede your questions, imposing my arguments over yours.”

It was a revolution of style, of language, made by a boxer. A true marketing intuition, before marketing appeared.

It wasn’t by chance that Ali was always starting his press conferences by reminding: “No one, not even the President of the United States [Jimmy Carter at the time], has the possibility to speak like me, on any occasion, and with so many newspapers, radio and TV stations.”

They were the last golden years of show business in boxing, transmitted through satellite to any corner of the earth, from the center of Africa, to the Philippines. It was, nonetheless, Muhammad Ali’s personality that kept everything standing, who dictated the show’s pace.

Once, before the rematch against Leon Spinks, with which he won for the third time the world championship he lost a few months before against his young challenger during a bad night, he spurned the journalists, saying they weren’t being fair to him. But, having a particular sympathy for me, he decided to derogate and to grant me an interview before the match.

We hadn’t even start talking when the producer from ABC, the network which had exclusive rights for that show in New Orleans, came in. “How dare you,” he screamed, “speak with this Italian after having denied everybody an interview, even to us who paid for this show!”

At that point Ali, who was laying down on the couch in his suite, stood up and said to the producer solemnly: “You bought my show, not my life.”

Ali was a true witness of his time, which he represented, and still represents, like no one else, including for the courage and the patience with which he faced for years the illness afflicting him, Parkinson’s disease.

A few years ago, after I accompanied him to a private visit to Pope John Paul II, who received him with extremely warm admiration, an unexpected connoisseur of his boxing, he said to me: “My God gave me so much in the first 40 years that if he takes away something now, we’re still even.”

Originally published at http://ilmanifesto.info/avversato-mai-sconfitto/ on 2016-06-05