Analysis

Monopoly’s anti-capitalist spirit resurfaces in Italian ‘Hacking’ version

Monopoly's original connection to fundamental components of the capitalist economy remained intact, so much so that it has periodically been revamped in an attempt to rekindle its original spirit.

Almost everyone has played Monopoly at least once, or at least seen others play it. With more than 275 million sets sold, it is one of the most successful board games in contemporary history. Not many people know, however, that Monopoly was conceived in the early 1900s by Elizabeth Magie, an American political activist, as an educational tool to explain the biggest problems of the land ownership system in her time.

So, it’s rather ironic that when Monopoly was patented, not only was Magie’s fundamental contribution to its creation left completely unacknowledged, but its original spirit was subverted. The result was a game that encouraged players to accumulate property, create monopolies and bankrupt their opponents. Despite all this, Monopoly's original connection to fundamental components of the capitalist economy remained intact, so much so that it has periodically been revamped in an attempt to rekindle its original spirit.

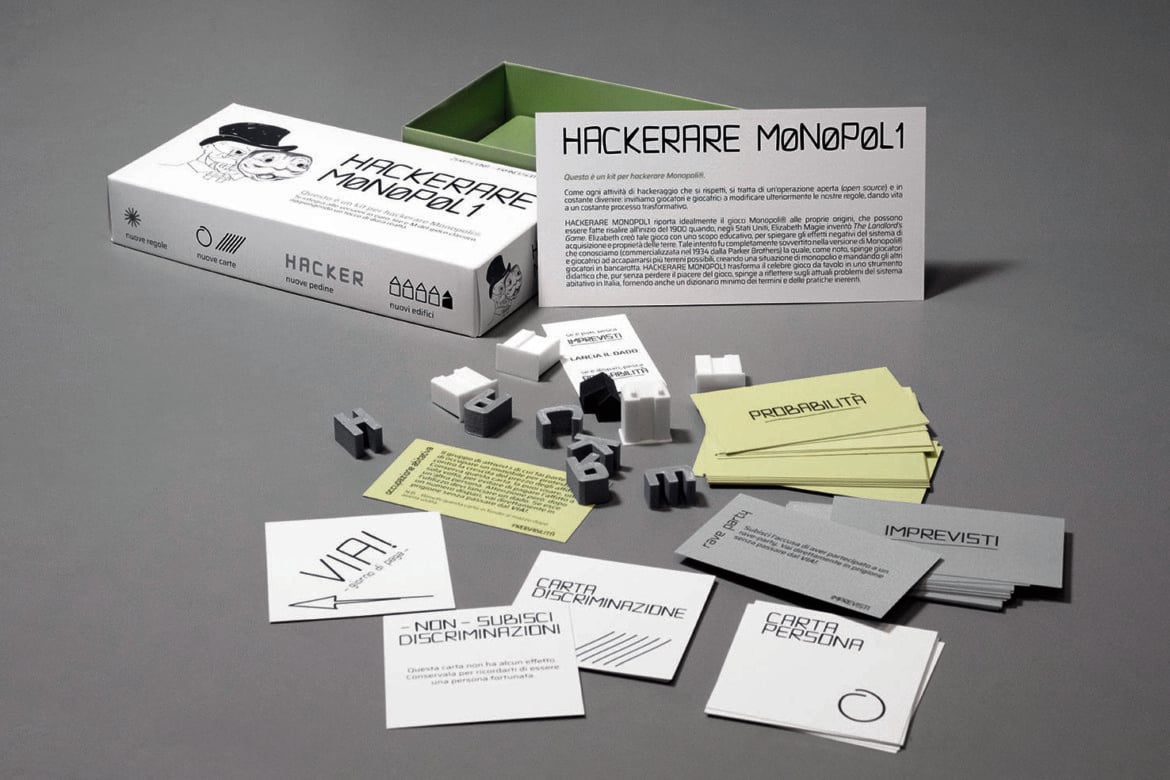

HACKERARE M0N0P0L1 (“HACKING MONOPOLY”, available in box form for a donation or in a do-it-yourself kit under a Creative Commons license) continues that tradition. It is an expansion pack which, when used with the classic version of the game, transforms it into what is technically called a “serious game” – a game that is intended to serve a purpose beyond pure entertainment.

The world of “serious games” – and, more broadly, gamification, the extension of game principles to non-playful contexts – is larger than one might imagine. For example, many of us have apps on our phones which encourage us to accumulate points to receive a reward, all to promote a product. Some may have even played America's Army, a popular war video game where one plays as a U.S. soldier on a mission, with tens of millions of downloads. It was launched in 2002 by the U.S. Army with the specific goal of encouraging young people to enlist. But serious games have always had an educational use as well. The theme of games also runs throughout art history: while Caravaggio and Cézanne painted the most famous “card players,” it was Marcel Duchamp who, starting in the mid-1920s, identified playing a game in itself, particularly chess, as an artistic practice.

This is the background for HM. Born from an artistic initiative, it was developed as a serious game designed primarily for the school system (middle and high school), but also for civil society (it can be used, for example, in the context of social movements for the right to housing). Its purpose is to foster a critical understanding of the processes, practices and policies that characterize the housing crisis in Italy.

This is achieved through what can be described as the “hacking” of Monopoly itself (an operation that gave the expansion its name and inspired its graphic design). The HM box contains materials that replace or supplement some of Monopoly's basic elements, inserting references to contemporary urban reality, all without losing the element of play.

For example, thanks to a complete rewrite of the Chance and Community Chest cards, players find themselves dealing with gentrification, housing occupations, urban DASPOs (removal orders against individuals for “anti-social” behavior), building amnesties, land registry reform, anti-Airbnb regulations, and the 110% “superbonus” for renovations. Some of these cards also allow one to build two new types of buildings, in addition to the classic houses and hotels: “Illegal Construction” and “Public Housing” (the latter allows players to remove properties from the market, but only until the “Privatization of public housing” card is drawn). All the topics mentioned on these new cards are explained concisely in a booklet included in the box, entitled “Small Dictionary of the Housing Issue,” which can be read during the game.

Furthermore, unlike in Monopoly where everyone starts with the same amount of capital, in HM each player draws a “character card” that assigns them different conditions of wealth (cash on hand) and property (some characters start the game already owning properties, some of which may be partially built upon). In connection with these, just as in the real housing market, there is the presence of possible discrimination, activated by a special card that limits the ability of the discriminated player to buy property.

But what is the point of this project? In a context where cities are increasingly undergoing transformations that accentuate their exclusionary, selective and inequitable nature, HACKERARE M0N0P0L1 has a modest ambition: to help promote literacy on issues of urban change and the housing crisis. Today, these topics are suffering from a “technocratic approach”: they are predominantly handled by a host of (supposed) specialists – journalists, architects, and economists – who give the impression that these are abstract technical subjects, too difficult to approach for anyone without a specific skillset.

But the centrality of these issues in the daily lives of millions of people, as well as their deeply political nature, demands a broader and more informed involvement in the public debate – a debate that perhaps even a game can help to fuel.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/monopoly-come-giocarsi-la-casa on 2025-11-15