Commentary

Milan Kundera and the ‘Czech Spring’ that emerges in his pages

He denied the political aims of his work, but the novel "The Joke" led to his censorship. In the 1967 Fourth Congress of Writers, he explained that the decline of literature was the result of Stalinism.

Milan Kundera would not be happy with this article, regardless of whether it says good things about him or not. He didn’t want his writing to be mixed with politics. Even more, he denied that his works had any political intent. Nevertheless, the Prague Spring and its atmosphere can be keenly perceived through many of his pages. The Spring became a European mythological stronghold that flourished between 1963 and 1968, mainly in the fervent creative imaginations of many artists from every field – literature, film, theater, philosophy, poetry – which then coagulated into an early ’68 government, to be snuffed out by Soviet tanks by August.

What about Milan Kundera himself? He was born in Brno to a pianist and musicologist father, and those in the know will find echoes of his upbringing among his writings. He was an enthusiastic communist in ’47, a year before the communist coup in Prague. Expelled from the Communist Party in in 1951, he was readmitted in ’56, back when many intellectuals in our country were leaving the Italian party of the same name because of the tanks going into Budapest.

At the Fourth Writers’ Congress of 1967, Kundera’s speech said in clear terms that the decadence of Czechoslovak literature had been due to the suffocating atmosphere of Stalinism, exported from Moscow and greeted with celebratory devotion by the leaders in Prague. He was not alone in thinking so: together with him, other myth-makers also proposed another possible world. It was a trip down the slide of History at incredible speed: a year later, the conference proceedings were published in a print run of 100,000 copies. During those years, in Prague and not only, endless queues would form in front of bookstores on Wednesday evenings and early Thursday mornings, because that was the day when new literary works came into stock, in both poetry and prose.

A whole crowd of intellectuals, of different training and backgrounds, had an effect on concrete history (no longer just imaginative), changing the sentiments of a substantial part of the population and initiating a transformation that only an avalanche of violence would be able to stop. It was a rare historical event, which had been in any case preceded in 1963 by a groundbreaking conference on Franz Kafka. At the time, there were no signs of his presence in the city where he was born and had lived. He was a writer deemed to be under bourgeois influence. The conference dismantled this rigid layer of dogma, and Kafka would be given a voice again to speak to his fellow citizens – until these days, when he has become a tourist prop.

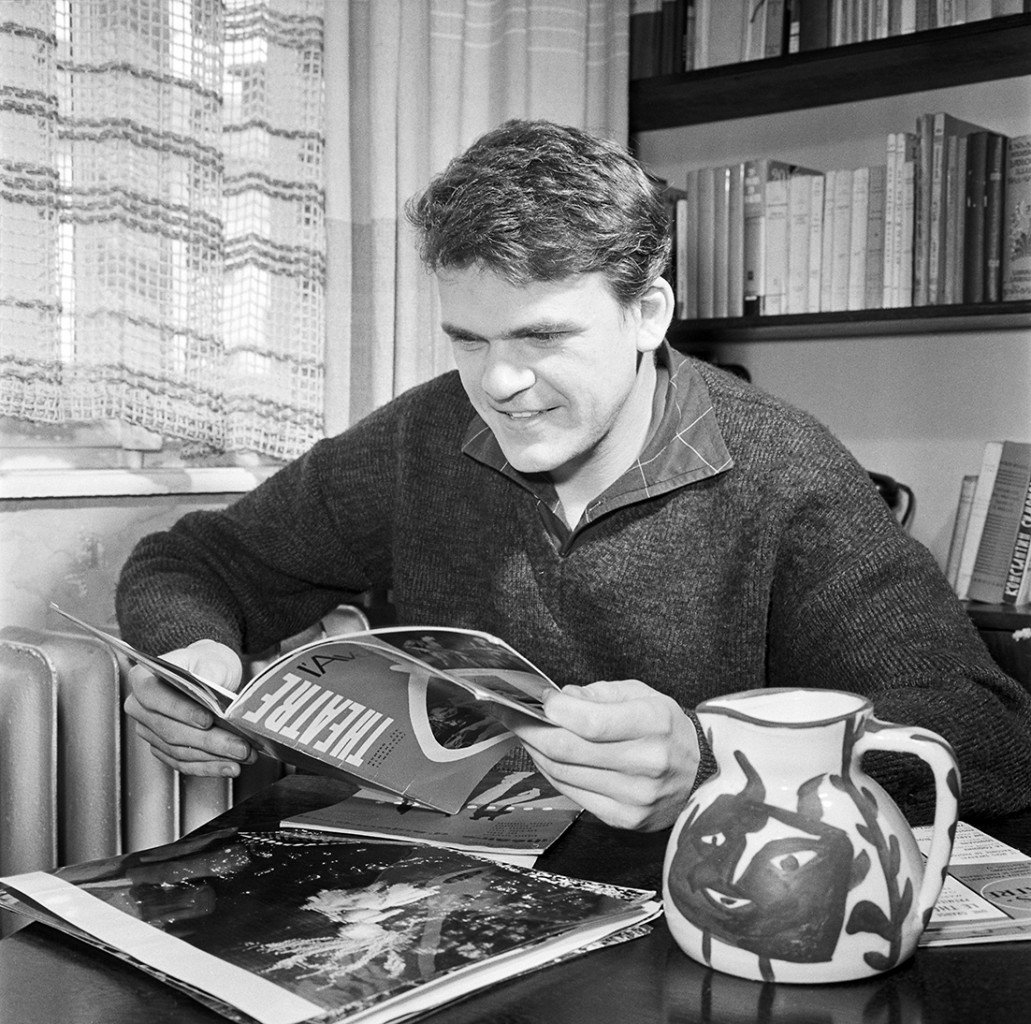

Two years later, Rossana Rossanda, who back then led the cultural section of the PCI, attended another conference in Dobris, together with intellectuals connected to the labor movement in the East and West. With her were Carlo Levi and Pier Paolo Pasolini, and the three stuck together. There, she recounted meeting extraordinary figures, such as “Karel Kosik, Antonin Liehm, Mancko and perhaps Kundera.” She must have met the latter again in Paris; she wrote about the season of the Prague Spring, prepared by a great intellectual ferment later obliterated by Warsaw Pact tanks: “Others engage in debates abroad. Kundera doesn’t think about the past except in a derisive manner, connected to what is being experienced and hoped for; unlike others, he does not want to be a ‘witness to the martyred fatherland.’ He is cosmopolitan and smiling, and, perhaps because of this, unmistakably Czech.”

In the early 1960s, Kundera had written a novel called The Joke, later published in 1967 (in Italy in ’69), in which writing a postcard addressed to a friend with a few sentences of regime ideology and the closing slogan “Viva Trotsky” would affect the young sender’s life permanently.

Then, Antonin Liehm, Kundera’s friend in Prague, crossed the Iron Curtain in early ’68 and went to Paris. He had Milan’s novel in his luggage. Gallimard gave it to a Czech reader, who said it wasn’t of interest. Between August 20 and 21, 400,000 Soviet soldiers, 6,000 tanks and 1,000 planes would forcefully explain to the Czechs that they had to change course. In Paris, the novel was given to Aragon, which had better discernment: The Joke was translated, and Kundera’s monumentalization began. In 1975, he left with his wife for the French capital and became a French writer. More than a decade later, his novels would be translated into Czech and published in Prague.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/milan-kundera-la-primavera-cecoslovacca-che-affiora-nelle-sue-pagine on 2023-07-13