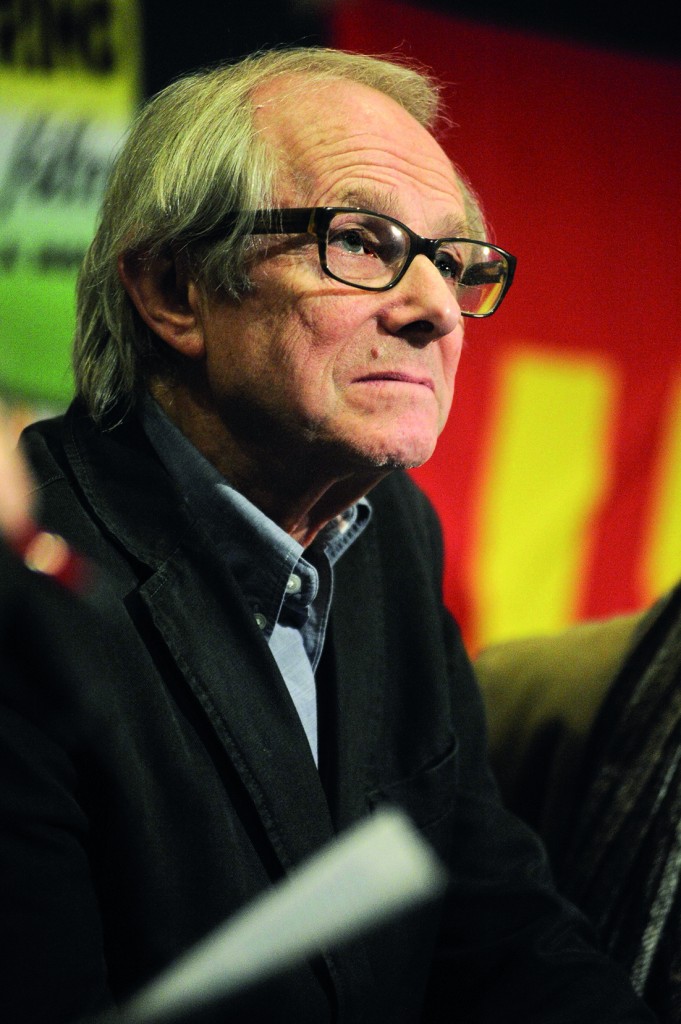

Interview

Ken Loach: ‘A market economy cannot prepare for a health crisis’

The coronavirus, the working class, the European left and future perspectives — a conversation with the British filmmaker.

Ricky, the protagonist of Ken Loach’s latest film, Sorry We Missed You, is a delivery driver, while his wife Abby is a care worker. Always close to the working class, the dispossessed, the common people, Loach tells the story of a family who barely survives in spite of their endless and tiring work.

Such characters, or rather people, come vividly to mind as Europe, and the world, are devastated by the coronavirus crisis and divided between those who can “afford” the lockdown and those who are forced to keep working, or risk losing their jobs. We reached the filmmaker by phone to talk about this crisis.

Reading the news these days, Sorry We Missed You keeps coming to mind: delivery drivers are among those who work — and risk — the most, mostly delivering non-essential goods, while the net worth of companies like Amazon is skyrocketing.

And also the care workers: they are even more in danger in our country, because they don’t have the protective equipment. To many of us it shows that a market economy cannot prepare for a health crisis like this. The market economy, and the politicians who represent that economic idea, just fail: they fail the people and fail to plan.

In our country there was no planning to provide the safety equipment, no planning to make tests, for extra hospital beds, until the disaster was upon us. And we still are not having tests, and doctors, nurses and care workers are still working without protective equipment. The care workers above all are suffering: now we have a big story everyday about care workers going into people’s homes – they may have the virus, but they don’t know – a lot of them work sick, the people in their homes are totally isolated.

And in the big residential homes, where a lot of old and disaabled people live, they are dying in great numbers. Once the virus has gotten into the homes, the workers have no protection, the old people are just kept in their rooms, many of them have dementia, so they don’t know what’s happening, their relatives can’t see them. The failure to plan just really exposes the right-wing government, they cannot plan and the consequence of it is so much worse than it needed to be.

Only a couple of weeks ago, the Prime Minister Boris Johnson was talking about herd immunity.

They had no overall plan so they are just running from one problem to the other. They knew the crisis was coming in January and it seems they did nothing. The other day, in the middle of the crisis, they were asking for companies to volunteer to make protective clothing: why didn’t this happen at the beginning of February, when they knew it was going to happen? Why didn’t they start to talk about the medical supplies needed for the testing? The free market government: that’s the problem. The idea that the state collectively organizes is foreign to them. The important thing to say goes to the heart of their politics: this is not a good system working inefficiently, this is a system that is inherently unable to plan. It’s an expose of capitalism itself, not of people who happen to be inefficient.

Here in Italy one of the reasons why the spreading of the virus is going down, but not enough considering that we’ve been in lockdown for nearly two months, is that many factories, especially in the North, have kept working. While some can “afford” the lockdown, others just keep working like nothing ever changed.

That is true also in Britain. The government gave very confused instructions, especially to people who work on building sites. The general instruction was: if you can keep two meters apart, then you can work. But building sites took this to mean to keep carry on working, but of course there is no way that building workers are going to stay two metres apart: everyone knows it, it’s ludicrous.

The other point to make, I think, is that it’s the working class that suffers most: because they are doing the manual work, and they are forced to work.

What do you think of the Labour Party’s new leader Keir Starmer?

I think that essentially he is a manager for social democracy, that his instincts are right wing. I also think he was very clever in continuing to work with Jeremy Corbyn, that he didn’t abandon him, because that kept him quite popular with the members. But in fact, he was responsible for the disaster of Brexit, the Labour position was a real disaster – and that lost us the elections.

But the choice of candidates was very poor. We had a left candidate [Rebecca Long Bailey], but she wasn’t as strong as some of us had hoped. Keir Starmer looks like a regular politician: he’s a middle aged white man, in a suit, he looks quite neat, he’s a lawyer, he can speak quite clearly in sentences and he can handle political conversation quite efficiently. But in terms of having any radical vision… He has none. The right wing voted for him, the mass media are very comfortable with him, because he performs in a way they’re used to.

I did a television program with him some years ago, and I found he had very little to say in terms of understanding the big class forces at work in conflict. He was about managing issues. I think he is a man who’s used to having an in-tray, takes the page out of the in-tray, writes an email, and puts it in the out-tray. And that I think is the extent of his vision.

What kind of vision would the Labour Party need right now?

It’s got to take a shot at the left. It would have to take down the whole privatization of the health service, because a lot of its functions are subcontracted to private businesses. That has to end. The big public utility should be brought into the public ownership, and also infrastructures: transport, the post, the telecommunications, the energy, water. The commanding heights of the industry should be transformed into cooperatives, or should be collectively owned, so that we can start constructing an economy that satisfies the demands of the climate issue, but also provides secure work.

And we also need big public investment banks to invest in the regions where there is real endemic poverty and no work, like the North East. There is a massive program, even staying within the confines of left social democracy, but it could be a stepping stone to a socialist economy.

But the big gap is: where is the European left? We had a possibility, with the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn, but in terms of the mass movement, nothing came from Europe: we were left isolated. That could have made a big difference. It was not only a defeat of the left in Britain: it exposed the absence of a coherent left in the rest of Europe.

The only mass movement that seems to have come out of these years is the one against climate change.

But it’s not based on class politics. It lacks a structural analysis of the dominant economy’s structure. You can’t control multinational corporations and tell them how to produce, where to get their raw materials. You can’t plan what you don’t own. And if we don’t own it we can’t plan it, and if we can’t plan it we can’t protect the planet. We need leadership: a mass of people will be motivated to organize if they see a big problem, but the point of leadership is to understand the roots of the problem and then lead on the basis of that. It leads back to Lenin’s idea of the Party: you’ve got to have a coherent analysis of the heart of the movement otherwise it just dissipates.

These days migrants keep flooding the borders of Europe, but we seem to have forgotten about them entirely, while they are also among the most exposed to this crisis.

Absolutely, they have no protection. Not only migrants: Syria, Rohingya, people in Gaza, in the West Bank. Oppressed people everywhere. The virus is probably the last thing they’re thinking about: they are just asking themselves, “Where am I going to eat? Where is my shelter for the night? Am I going to survive tomorrow just as things are?”

People are packed together in poverty in the Greek islands, in refugee camps and in favelas in Latin America. Once the virus gets a grip there the prospect is terrifying. I think what it shows is that there is a problem inherent to international law, in the United Nations: we need international law that can be enforced, but as long as countries like the United States — and China, and Russia — don’t accept it, refuse collective responsibility, what we can do is very little. The United Nations in the end is a campaigning organization, it can’t enforce anything. And without that we are lost.

The European Union too doesn’t seem to be playing a positive role.

Italy, like Greece, has been left alone. Northern Europe turned its back: we are meant to be in it together, but you sort it out. The hypocrisy of the European Union is just disgusting when they are faced with a real problem to share. I don’t agree with Angela Merkel politically obviously, but she did at least react in a humane way.

How can, or should, cinema tackle this crisis when the time comes?

The overriding issue for cinema is that we’ve got to have cinemas, in towns and cities, because the drive to just see films in your own home, the Netflix model, to me is disastrous. Cinema is seeing films in an audience. The choice of films in the multiplexes is getting smaller and smaller, independent cinema gets pushed out. The only ways to survive, I think, is for theaters to be owned by the municipality, programmed by people who care about films. It needs political interventions, so that we treat it like art galleries, and public money is invested in cinemas that’ll show world films: European, from the Far East, Latin America, Africa, and America of course. It could be great places and you could really enjoy films again, with an audience.

Comedies for example: laughter is infectious, if you sit and watch a comedy in your own home you’re not as likely to laugh as if you’re sitting with a crowd of people laughing. And if there’s something moving or tragic, you feel it more in an audience than if you’re just sitting in your own room, stopping now and then to make a cup of tea.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/ken-loach-il-volto-disumano-del-libero-mercato-nella-crisi-sanitaria/ on 2020-04-21