Commentary

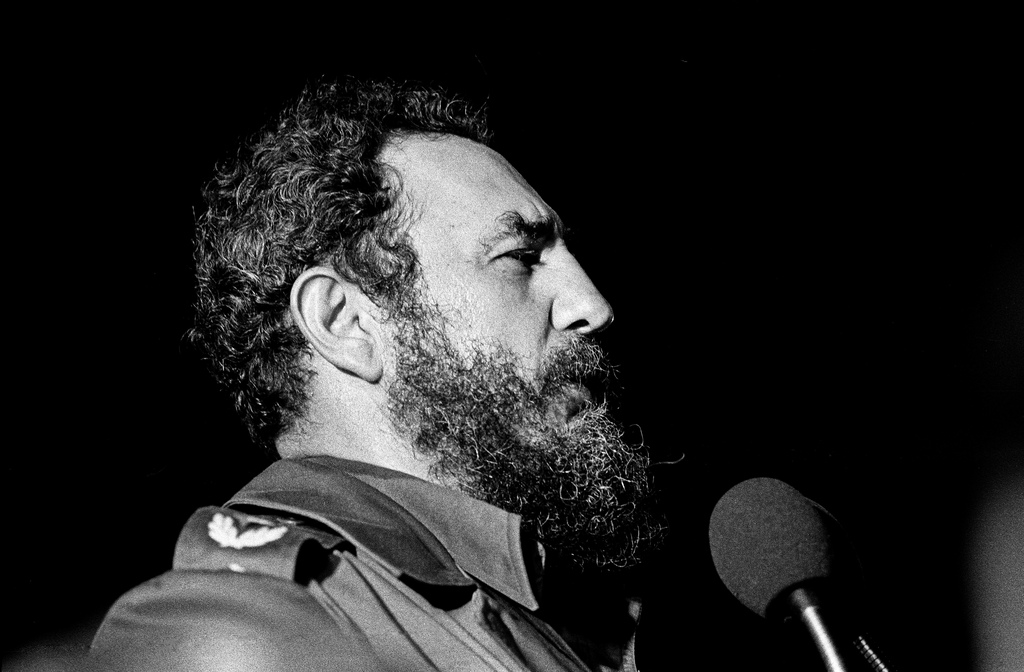

'History will absolve me'

Fidel Castro stood up to the United States while projecting a vision of justice for the world.

With a clear example of absolute discretion, the Commander Fidel Castro left this world on Friday, the only leader in the modern world who started a revolution and never lost it. The only leader who has left a country in better shape than when he risked his life to free it from the tyranny of dictator Fulgencio Batista, who ruled under the arm of the Mafia.

It is remarkable that these realities, irrefutable for Latin America (Operation Condor, desaparecidos) are still not adequately recognized and remembered by a part of the Western world that, in recent years, has reached unprecedented levels of persecuting human beings like us and filling their mouths with the words “freedom” and “democracy,” when in fact, their only “merit” was to be born in the right place, at the right time.

This logic was instead was very clear for the young lawyer Fidel Castro, since the time of the student revolts, when after being arrested for his sedition, he defended himself in court with a legendary proclamation: “History will absolve me.”

In fact it is more than dishonest, that the Pharisees of our house (the so-called reformists) ignore that Cuba has paid a very high price for the stubbornness of its commander, with the absurd embargo that has lasted more than 55 years. Just for having claimed the right to self-determination of their people choosing a system the United States did not like. In short, a punishment of absolute arrogance.

This perverse mechanism has meant, however, that 70 percent of the citizens currently living on the island have grown crushed by the repression of the North American embargo.

It is not surprising, then, that this resistance was the sin that someone continued (and continues) to blame Fidel Castro for, in spite of the fact that he left the political scene 10 years ago due to his poor health.

Yet it is no secret that for years, almost all the leaders and Latin American heads of state always made a stopover in Havana after returning from meetings up North (U.N., multinational). They wanted to hear the opinion of the commander on the ransom on Latin America and its future to choose despite the criminal policies of the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank or the New York Stock Exchange. There are those who are convinced that Fidel’s retirement had dealt a blow to the evolution of some political and social processes in other countries of the Southern hemisphere.

Not surprisingly, almost all over the world, the news of his demise was treated with absolute respect, except perhaps by some factions in Miami, those which have encouraged organized terrorism from Florida to be implemented in Cuba, like Posada Carriles did, who continues to walk safely to Miami. It’s about time, indeed, that someone asked the truth to the U.S. itself.

It is not a coincidence that the Catholic Church, in keeping with the attitude of Pope Francis against violence and war, chose to commit his diplomatic efforts to resolve complicated situations stuck in time, and choosing not once but twice, Cuba as an environment for peace negotiations.

I cannot deny that, as a citizen of the globe in search of truth, even before my role as a journalist, I now feel the lack of a protagonist of history. Critics will say he was often wrong, but at the same time he sacrificed himself to respect the rights and the dignity of all.

Even the Pope must have noticed it when he paid a private visit to Fidel a year ago, accompanied only by a monsignor and thus providing a tangible example of sensitivity to the world.

That sequence I inserted in the documentary film “Pope Francis, Cuba and Fidel” bears witness to an emotional tenderness. The pontiff took Fidel’s hand and urged him: “Hey, from time to time, throw one Prayer to our Father,” to which Fidel unexpectedly answered: “I’ll remember.”

When 30 years ago, a combination of life, favored by Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Jorge Amado (jurors at the La Habana Film Festival), allowed me to meet Fidel Castro, I realized right away the personality of this protagonist of history.

With an obvious kindness, I asked him before the interview if, as all heads of state, he wanted to know the questions in advance. It was dramatic: “No. With the history we have, can we be afraid of words?”

The interview, granted subsequently, lasted 16 hours and was published with two prologues, one by Garcia Marquez and the other by Jorge Amado.

During Pope Francis’ visit to Cuba in September 2015, I was surprised to see the 90 year-old Fidel in a wheelchair, but lucid. Someone had told him that a film crew was documenting that unexpected encounter and we were full of hope. He called us into his house and, in addition to explaining to us the embarrassing situation of the issue of migrants and the underprivileged in Europe, he spoke with great enthusiasm about the Argentinean Pope: He said: “His style does not surprise me at all, because essentially this is a very honest person, very sincere and disinterested.”

It was the last time I saw him.

I had promised to go in mid-December to attend the La Habana Film Festival and bring him a copy of the documentary. I did not have the time to do it, but his speech at the Party Congress, a few months later, struck me. Not so much the phrase: “Soon I will be 90 years old. That idea had never occurred to me and it was not the result of an effort, it was the case. Soon I’ll be like everyone else. Everyone’s turn arrives.”

I was excited by this statement full of hope: “The ideas of Cuban communists will remain as proof that this planet, if you work with fervor and dignity, is capable of producing the material and cultural goods human beings need. … We must convey to the people that the Cuban people will win.”

Originally published at on