Analysis

Giovanni Brusca could not be kept in prison forever – should anyone?

Brusca’s case brings to mind the similarly-timed indignation about the recent ruling of the Constitutional Court that life imprisonment with no parole is unlawful.

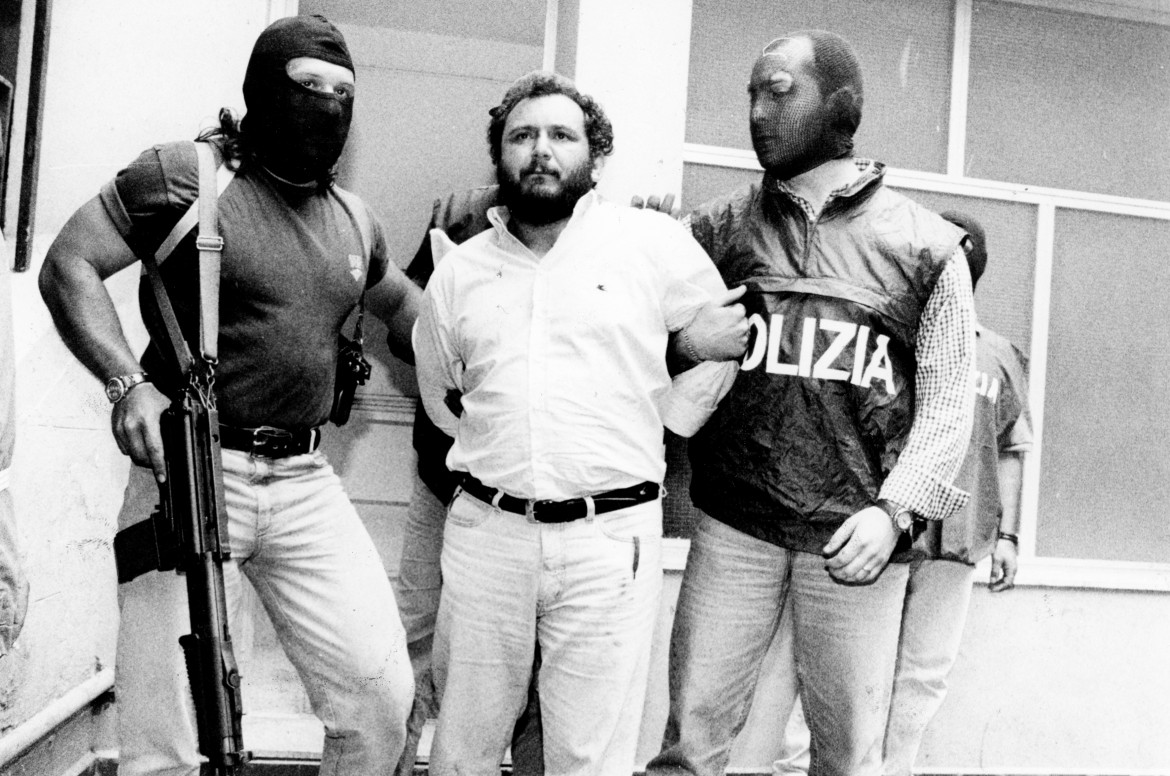

Giovanni Brusca, a serial murderer for the Mafia, has been released from prison after serving a 25-year sentence. As we recall some of his many victims—such as Giovanni Falcone, Francesca Morvillo, the agents accompanying them, and, most appalling of all, little Di Matteo—many are showing great indignation and even amazement at the small sentence he served, and, of course, at his release. However, his release is justified by law, which, if it protects all of us equally, must protect Brusca too.

The death penalty has been rendered illegal in the Italian justice system by article 27 of the Constitution. The maximum penalty is now life imprisonment, which, however, is never served in its entirety, given that a lifer (like anyone else sentenced to prison), after successfully undergoing reeducation, can be awarded various benefits, such as working outside the prison, furloughs and alternative measures to detention, up to and including early release.

However, a number of laws concerning those convicted of a number of specific crimes (Mafia- and terrorism-related, first of all) have allowed the granting of these benefits only to those who cooperate with the justice system. Accordingly, the legislator has set up, with Article 4-bis of the Penitentiary Law, the possibility of a perpetual life sentence, with no possibility of parole, for those who do not want to cooperate.

Giovanni Brusca didn’t have to show signs of inner contrition (something easy to display and difficult to assess), but he did cooperate, giving the judges elements that shed light on the Cosa Nostra and on many of its crimes.

In other words, Brusca made a deal with the state on grounds of mutual benefit, and the state has respected this deal, first by commuting his life sentence, and on Tuesday by releasing him after he served his time.

A state under the rule of law could not do otherwise: you can’t praise the laws offering benefits to informants when they lead to victories in the courts and then badmouth the same laws when they show their hard-to-swallow consequences, especially for the victims and their relatives.

Brusca’s case brings to mind the similarly-timed indignation about the recent ruling of the Constitutional Court that life imprisonment with no parole is unlawful.

It is obvious that this type of life sentence, which is supposed to never end under any circumstances, is in conflict with Article 27 of the Constitution, which states that “punishments may not be inhuman and shall aim at re-educating the convicted,” a re-education that must logically lead, sooner or later, to the possibility of their release.

The Court found that life imprisonment without parole fell within the prohibition set by Article 3 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, according to which “no one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”

Similarly, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) has long ruled that this type of punishment does not comply with the Convention.

The Italian Constitutional Court had previously found that a blanket prohibition to ever release a convict who hadn’t cooperated with law enforcement but had undergone re-education and no longer had any contact with organized crime also violated the Convention. However, after the inaction of Parliament on the matter, on April 15 the Court ruled that this punishment violated the Italian Constitution as well, namely Articles 3 and 27.

The ruling gave the legislature one year to make the Italian framework comply with the Convention, since “the immediate adoption of the ruling would risk being inadequately integrated in the current system of combating organized crime.”

There is one year left, but the end of life imprisonment without parole is inevitable: if the Parliament drags its feet, this will lead to another intervention of the Court, which at that point would rule it unconstitutional with immediate effect. This is a cause for celebration, as it shows that a number of institutional mechanisms are working and reaffirming the rule of law. However, this decision also opened the floodgates of criticism and outrage. For instance, CSM Councilor Di Matteo went on TV and called the abolition of life imprisonment without parole a capitulation to one of the items on the list of demands with which the Mafia under Riina had blackmailed the Italian state. There were also insinuations that a backroom deal must have been made between the judges in Strasbourg and those of the Constitutional Court.

Some states have already begun to remove life imprisonment from their penal systems altogether (Spain, Sweden, etc.), but what should hit closest to home is the abolition of life imprisonment in the legislation of the Vatican, a punishment that Pope Francis has repeatedly equated to a death sentence deferred over time.

Of course, it’s hard to conclude from these faintly positive signals that Italy could reach such an advanced level of legal civilization in the near future—but they should be enough, at least, to quell the indignation at decisions that respect the Constitution and the laws that follow it.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/lo-stato-di-diritto-non-puo-fare-altrimenti/ on 2021-06-02