Analysis

European Parliament will be split, but not hostage to nationalists

The far right, loud but fractured, will make only modest gains in the European Parliament in May elections, according to a massive new survey compiled by Kantar Public, occupying a quarter of the seats.

As we cross the 100-day mark in the countdown to the European elections May 23-26, the results of the largest European public opinion survey so far, compiled by Kantar Public on behalf of the European Parliament, can be read with some optimism, although not for Italy in particular.

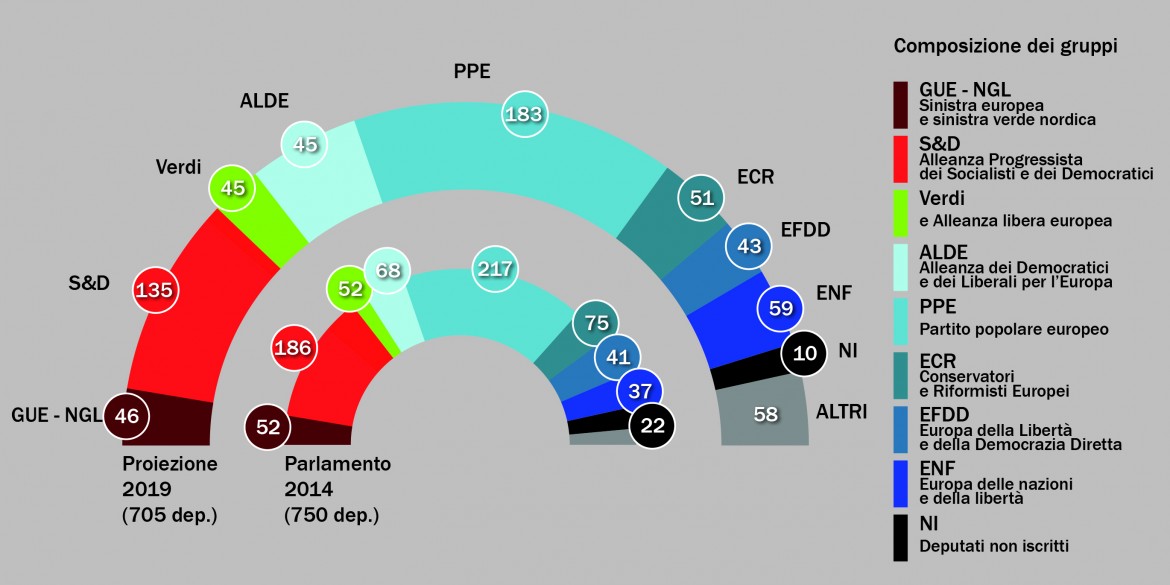

Indeed, Steve Bannon’s dream of building a nationalist majority that would be hostile to European integration will not be realized: of course, the Lega will make gains, and one of the current three far-right groups, the ENF, will substantially increase its numbers, with a forecast of 22 more parliamentarians (from the current 37 to a predicted 59), largely on account of the Lega, which is projected to gain the largest number of seats in Italy and the second-largest in the EU, and Marine Le Pen’s National Rally. However, this gain, taking the ENF to 8 percent, will be offset by the stagnation or decline of the other two far-right groups.

One of them, the ECR, will have to contend with the absence of the British Conservatives, while the other, the EFDD, where the M5S sits, will suffer from the absence of the UKIP, and might even dissolve altogether if the Italians and the German AfD decide to join other groups.

Overall, the nationalists will occupy a quarter of the seats of the new European Parliament—a notable result, but very far from a majority (which would require 353 members), with about 160 seats compared to their current 151 (rising just a few percentage points from the 20 percent they have today).

Moreover, the far-right parties are deeply divided among themselves, both when it comes to the economy (some of them are ultra-neoliberal), foreign policy (featuring divisions between the westerners, who are more pro-Putin, and the Eastern Europeans who have much less of a pro-Russian stance), and the large transnational issues, such as immigration, where the nationalists seem unable to agree on anything beyond each following their own interests. At most, the extreme right will have the power of “negative cohesion,” while the weight of the nationalists will be stronger in the Council, where, given the prominent role of unanimous decision-making, the governments which include the extreme right have effective veto power.

Another significant takeaway from the survey is that the issues that present the most interest to the citizens of Europe—immigration, the environment, and even terrorism—are all of a transnational nature. Too bad, however, that there are no transnational lists—a project that was nipped in the bud for this election, despite some efforts to support it, by the Christian Democrats of the PPE.

The new European Parliament will be much more political than the incumbent one, because it will mark the end of the German-style model of the Grand Coalition between the PPE (Christian Democrats) and the S&D (Socialists and Social Democrats), who used to be hand in glove, even dividing the top positions among themselves, as they held 55 percent of the seats. The new Parliament will have 705 members compared to the current 751 (as part of the seats no longer held by the UK will be divided between other countries—for example, five more for France and three for Italy). The absence of the British Labour Party (and the collapse of the French PD and PS) will cut into the S&D group.

The EPP will be the largest group, but it will have lost seats as well. No group will have more than 200 members, and the European Parliament will be more divided than it has ever been in its history. It will need more compromises, and more time to put them together—but the risk of gridlock is not very high, since most votes only require a simple majority.

Paradoxically, at a time when concerns about the environment and climate issues are getting more and more acute, the Greens are set to lose seats (also because environmental awareness is spreading out across other political formations as well), but ALDE, the centrist liberals, are set to grow in importance, as they may be joined by the newly elected members from LREM (Macron’s party, which will elect around 20 parliamentarians, plus two from their allies, MoDem).

Further left, there are still many unknowns: the Kantar survey predicts that the far left will win 46 seats, but other polls go as high as 58 seats (depending on what the Greek Syriza will achieve, as well as Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s La France Insoumise). The possibility remains that the GUE group will be revamped, as it is currently riven by divisions on various issues (first and foremost migrants, an issue that has already caused a split in one of its member parties, the German Die Linke).

The bad news is that, according to Kantar’s predictions, there would be the possibility of a majority in the new European Parliament on the Austrian model, with an alliance between the Christian Democrats and the extreme right. However, the question of anti-Semitism will most likely prevent such a deal. Still, it should be noted that the EPP group is shifting more and more towards the far right: it contains, after all, Viktor Orbán and his Fidesz, and the latest statements on Istria and Dalmatia by the current president of the European Parliament, the Italian Antonio Tajani, are showing a worrying nationalistic drift.

The end of the EEP-S&D dominance will also break the previous “spitzenkandidat” system for electing the president of the Commission, who was previously nominated by the leaders of the two largest groups—a system which led to the election of Jean-Claude Juncker in 2014. Accordingly, it cannot be taken for granted that the candidate nominated by the EPP, the German Manfred Weber, will end up being the next president of the European Commission (since, according to the Lisbon Treaty, the European Parliament elects the president of the Commission after a candidate is nominated by the Council).

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/un-europarlamento-spaccato-ma-non-ostaggio-dei-nazionalisti/ on 2019-02-19