Analysis

‘Don’t we deserve a renewable future, too?’

Africa is a natural candidate for the energy transition. But European investments are focused on gas projects.

In 2007, Greenpeace and the European Renewable Energy Council published \Energy(R)Evolution|, a study and proposal with a global scope. For Africa, the “(r)evolution” called for a sharp increase in the share of renewables and energy efficiency, the replacement of traditional biomass (i.e. firewood, tied to exhaustion for women and indoor pollution that is claiming many victims) and a reduction of climate-changing emissions per capita from 0.9 to 0.6 tons of CO2 (combined with a reduction from 15.6 to 3 tons in in OECD countries).

Now, on the eve of the Italy-Africa summit, the Italian climate think tank Ecco has published a paper entitled Il focus italiano sull’Africa: opportunità e rischi del piano Mattei (“Italy’s Focus on Africa: Opportunities and Risks of the Mattei Plan”). The current diplomatic and financial paradigm between Italy and African countries seems designed to favor the traditional goal of ensuring access to fossil fuels (a need accentuated by the war in Ukraine). But if Italy, the European Union and the G7 were really willing to inaugurate a new, inclusive, sustainable and forward-looking strategy, it would be necessary to “overcome energy narratives linked to traditional notions about energy security” (new investments in hydrocarbons as Italy’s foothold in Africa are not necessary, quite the contrary: they are now an economic and financial risk).

The rhetoric that fossil fuels would bring economic and social development to African countries also needs to stop. Given the high volatility of international markets, “investing in oil & gas is increasingly risky” for them as well, all the more so when tying national debt sustainability to revenues from fossil fuel projects.

The paper points out that Africa is a natural candidate for the energy transition, given that “it has about 60 percent of all areas suitable for photovoltaic electricity generation across the globe, as well as large oceanic coastal areas ideal for wind power, river basins for hydropower, and great geothermal potential, especially in the Rift Valley.”

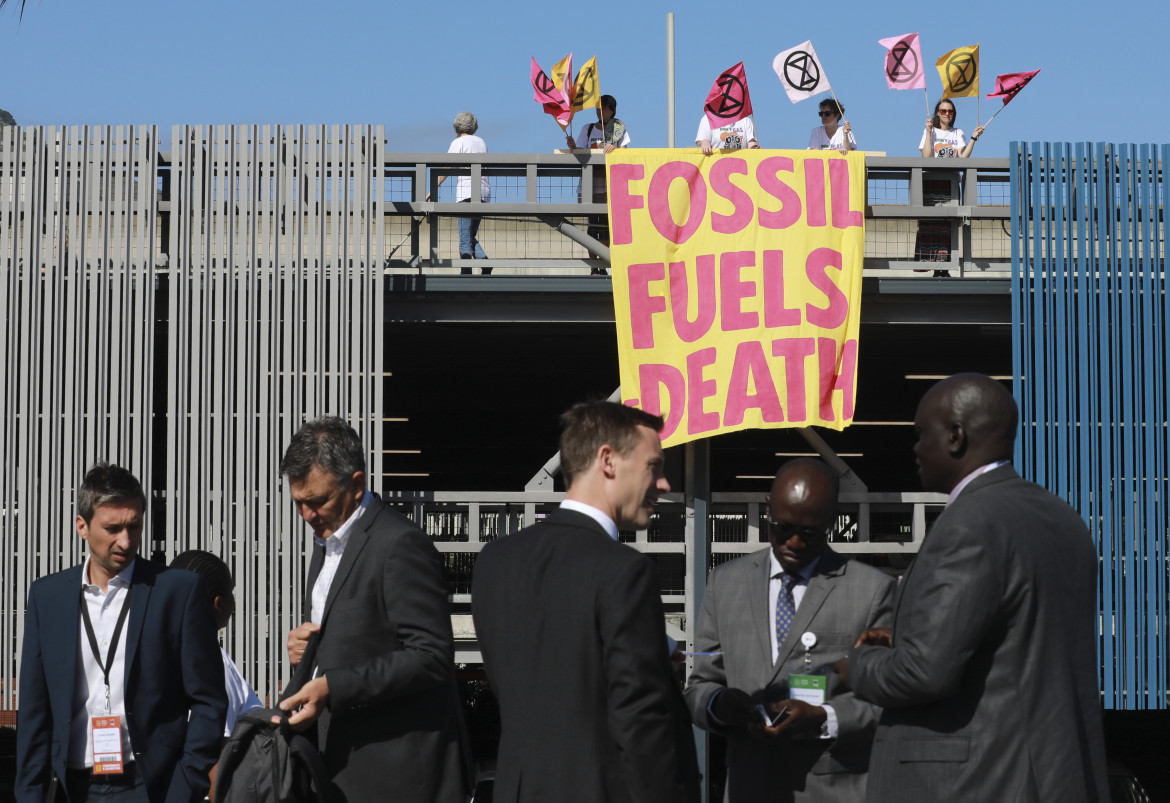

So far, all these alternative energy sources have received little funding compared to gas projects. In October, at the first African Climate Summit, governments across the continent called for global support to quintuple their renewable energy capacity.

Redirecting funds towards renewables would result in greater economic stability, more local jobs and positive secondary effects on the climate. Those who are insisting on migration policies should think carefully: massive population shifts are induced by extreme weather events and food and water insecurity.

On the eve of the COP28, Vanessa Natake, a Ugandan climate activist, wrote in The Guardian that “right now, only 2% of investment in renewables goes to Africa … don’t we deserve a renewable future too?” Will rich countries’ “thirst for African gas,” with the heavy environmental contamination that comes with it (the so-called “resource curse”), “keep holding Africa back by making us a dumping ground for the dying fossil fuel industry? Or will they finally let us lead the world in delivering a secure, just and clean future?”

Ecco also stresses the African reserves of critical raw materials such as cobalt, manganese and platinum group metals, minerals critical for batteries and hydrogen technologies. Here, however, there is the thorny issue of extractivism, even if aimed at ensuring others’ transition, which is the focus of a report by War on Want, together with the Yes To Life, No To Mining global network, entitled A Just(ice) Transition is a Post-Extractive Transition (2019).

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/estrattivismo-a-casa-loro-energie-rinnovabili-addio-in-africa on 2024-01-28