Remembrance

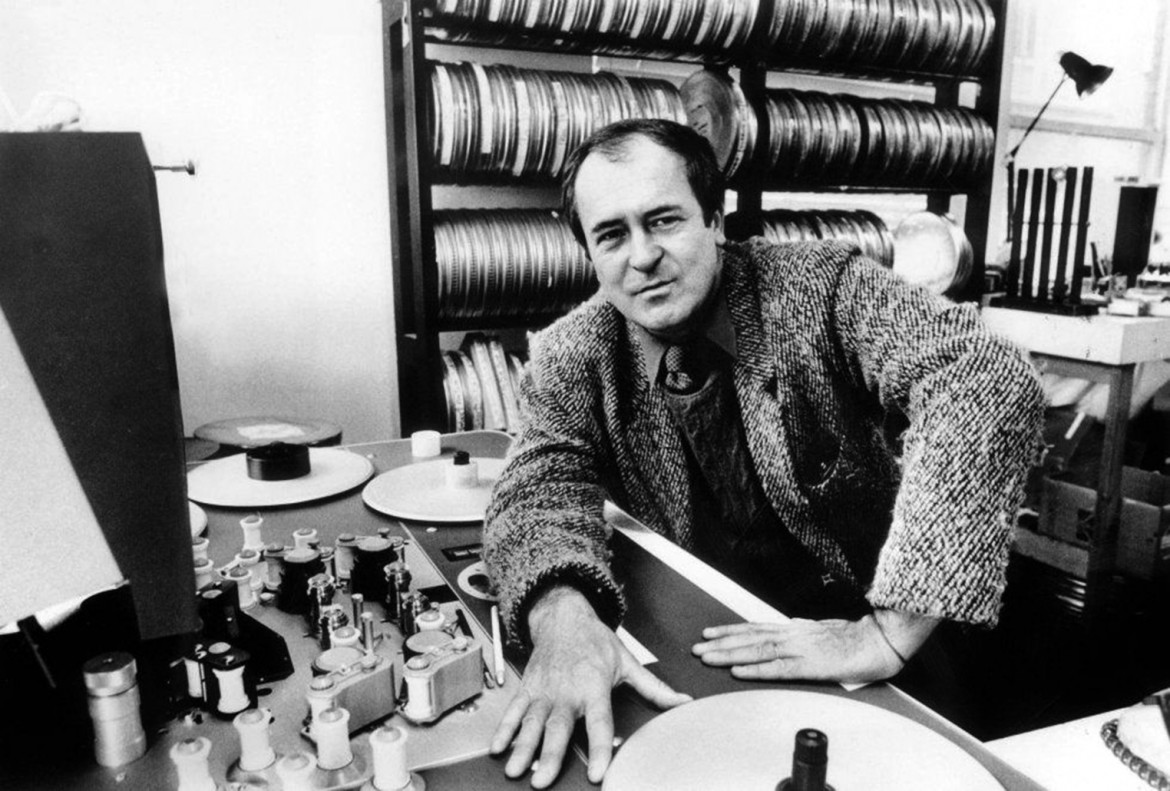

Bernardo Bertolucci told the story of modernity

The legendary filmmaker died Monday at 77. He used the cinema to explore the tapestry of reality. ‘Pier Paolo told of the sociological and cultural transformation of Italy, from a peasant country to a consumerist one. I wanted to show him that the peasant innocence that he thought was gone was still there.’

It is always difficult to deal with news that catches you unprepared. It’s true that Bernardo Bertolucci had been ill for some time, but he had continued to make plans, to leave possibilities open, to go on with what is truly a life’s work with a new film he planned to make, still at the writing stage, perhaps just a “small” one like his previous—and magnificent—Me and You (2012). This film was in equal parts unsettling, with an unexpected and unpredictable energy that made me think while watching that it looked like a young man’s movie. But that is what he was, a young man…

And now, suddenly, he is gone, and the clock is ticking: I have to write, say something, rethink all his movies, in a retrospective which is also that of the life into which those films entered with their delicate arrogance, becoming an irreverent “guide” for the spectator’s gaze.

What did Bertolucci’s cinema teach us? What does it still teach us, and what will it keep teaching us in the future? Desire and revolution, the sensuality of the camera, and that famous line, “You can’t live without Rossellini” (from Before the Revolution), which has almost become “You can’t live without Bertolucci,” even while he remained a figure unlike anyone else in Italian cinema. And that is not just because of the shots he chose, or his staging, or his stories. It’s something else, something very different and much more than that: the space of the imaginary, the pleasure of filming, the discovery of the world together with its invention.

And it matters little whether it all happens in a cellar (Me and You) or in the Forbidden City of Imperial China at the beginning of the 20th century (The Last Emperor): his “mother scenes”—the term Enzo Ungari used in his book, who was one of the writers of The Last Emperor—render the complex plot of reality and of the times into a universal, free and critical attitude, one that probes all certainties and interrogates its object without ever taking shelter in an “ideology.” Even more, there was his ability to transplant what is rooted to a certain place onto the world stage, to open up cinema to a global dimension, at the same time that, beyond the circumstances of its production, it continues to bear its own unmistakable imprint.

All Bertolucci films live on a border, in a play of mirrors between inside/outside, in the establishment of a self-aware point of view that declares the presence of the author with his experience transformed into narration, his cinephilia—much more as acts of love than mere references—his friends, his myths, his childhood in Parma. Even the dance scenes, or the “obligatory” scenes set in the desert or in the cinematic Far East in his beloved films—or, indeed, those set in a villa in Tuscany where a young American experiences her coming-of-age story (Stealing Beauty, 1996)—since after all, at bottom, all his movies are coming-of-age stories. He is in there, with his stories that he loved to tell, a refined storyteller who never got tired of listening, adding further variations every time.

The hypocritical and hyper-clerical Italy of 1972 quite literally burned his movie The Last Tango in Paris at the stake, sentencing Bertolucci to lose his civil rights for five years. That film was indigestible at the time because of how it reversed the representation of sexuality, the relationships between man and woman, within the Nouvelle Vague vision of uniting European and American cinema. Even decades later, the controversy continued, with the accusations that he had psychologically traumatized Maria Schneider in the infamous “butter scene.” Yet it is she—her character, who lives two lives, one inside and the other outside that apartment—who comes closest, perhaps even more so than Brando’s character, to being the icon of an American cinema contrasted with the ghosts of the Nouvelle Vague, of the thrill that comes with that desire for transgression (again and again), which clashes with the world beyond the walls of the apartment in Passy where the encounters between the two characters take place.

His film 1900 (1976) was attacked by the Italian Communist Party—at least by the older generation—which accused it of being unrealistic, as a son from a peasant family could never be friends with a son of landowners, as happens between Olmo (Depardieu) and Alfredo (De Niro), both born on Jan. 27, 1901, the day when Verdi died. But Bertolucci’s source of inspiration was his childhood in the Emilia countryside—he was born in Parma in 1941—where he was playing with the children of the peasants as a boy, and also where, as he liked to recall, he had first learned the word “communist.” Bertolucci did not appropriate the position of the peasants; on the contrary, he maintains the consciousness of being bourgeois, and this allows him to move from reality as it is to the utopia of the Revolution—and of cinema.

This is the political substance of his images, incomprehensible to the Italian critical thought of the time, which laid emphasis on the “content.” But Bertolucci was looking elsewhere: he traveled in time and space, and immersed himself in the unconscious to capture the conflicts, the division between “I” and “us.”

In the fateful year 1968, it was Pierre Clementi (the protagonist of Partner, which Bertolucci wrote together with Gianni Amico) who brought the spirit of Paris closer to Rome—“They were waiting for his stories,” Bertolucci said. The youngsters in The Dreamers also found themselves closed up in an apartment, only to finally go out into the streets and, when faced with reality, take different positions, which ended up separating them forever—with the remarkable synergy between Bertolucci and the blond Michael Pitt, themselves dreamers who managed to join together the imaginary and lived experience within a single breath.

Cinema, desire, revolution: the memory of a night of illicit whispers on the beach in Sabaudia (where Bertolucci owned a home) between a boy and his mother in the tormented drama La Luna (1979), and the breast that feeds the baby who is the Last Emperor. But the unconscious is always that of a particular human being, of a country, or of history—of the 20th century and of ours. It is no coincidence that, in his story of a family struggling to cope with the kidnapping of their son, which might have never happened—The Tragedy of the Ridiculous Man—Bertolucci was the only Italian director who in 1981 was already accurately highlighting the disorientation of politics and of the left in the face of armed conflict, the big taboo of our collective imaginary.

Pasolini was at his side at the start of his career (together with whom he wrote his debut, La Commare Secca, in 1962)—a photo shows them both together, wearing suits and ties (this was before there was such a thing as young people’s fashion), with Bertolucci looking curly and beautiful. Among the stories he told many times was that of their first meeting, when Pasolini had come to look for his father, the poet Attilio, while he was resting at home. Bernardo had kept him waiting at the door a little impolitely. His father scolded him at length for that, and from that moment, a deep connection developed between the two young men, an avenue of communication, even if they had different worldviews.

“Pier Paolo told of the sociological and cultural transformation of Italy, from a peasant country to a consumerist one. I wanted to show him that the peasant innocence that he thought was gone was still there,” Bertolucci said, again on the topic of 1900.

What else should be mentioned? Nine Academy Awards (for The Last Emperor), just one of the signs of an increasingly international dimension to his work—a result not just of working with actors from all over the world, of his passion and curiosity, his elegance and his stories, but above all of his love for cinema. Nor did he ever see cinema as an end unto itself—one never sees in his films the self-importance that can come with the sheer act of filmmaking, even while Bertolucci’s eye manages to weave a tapestry of spectacle out of every detail, but rather a feeling of modernity itself—and the wager that, after all its variations past and present, it is still able to surprise itself.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/il-desiderio-e-rivoluzione/ on 2018-11-27