Analysis

Austerity and the limits of the Draghi plan

The Italian budget plan cuts spending, showers gifts on the usual suspects and lacks any strategic vision. This is more troubling since France, Germany and other countries are also cutting back. That’s why it’s important to seriously consider the strengths and weaknesses of the Draghi plan.

The seven-year budget structural plan prepared by the Meloni government is certainly not without its gifts and perks for the usual suspects, such as the extension of the flat tax (which allows a self-employed person to pay 15 percent in taxes while an employee pays 27 percent on the same income) or the 21st amnesty for tax evaders.

It is also restrictive with regard to spending – with a cut in real terms that will affect schools, health care, public investment, compared to the enormous waste that is the Messina Strait Bridge. Above all, it lacks any strategic vision or coherence as a project.

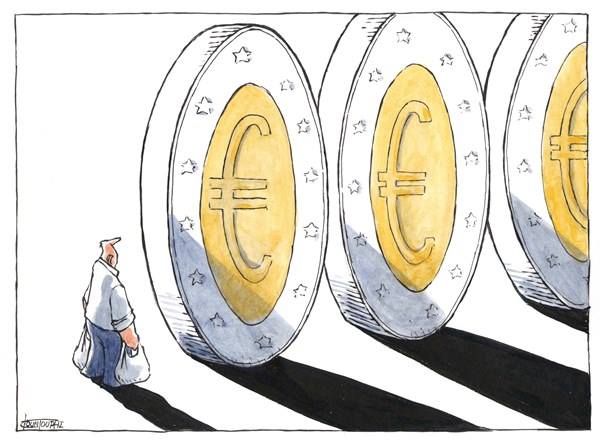

And this is all the more serious when one takes into account the fact that other countries, such as France and even Germany, are in financial difficulty and thus are being forced to adopt restrictive recovery plans similar to the Italian one.

This will lead to a compounded, disproportionate worsening of the depression-inducing consequences of the increase in overall restrictiveness, given the interdependencies between sectors, especially with regard to imports and exports. The fact is that this aspect – the simultaneous budget rebalancing plans of multiple countries which can operate as an additional restrictive factor – was little considered when launching the new European governance structure.

In this situation, the only antidote to stagnation and/or recession is the possibility that some form of inspiration such as the one that animates the Draghi plan will nonetheless make itself felt at the European level. This is why it is all the more important that we discuss both the Draghi plan’s shortcomings as well as its merits, of which the most important is proposing a “conceptual framework” for development that would center on investments to the tune of €800 billion per year until 2030.

These possible investments (which so far have only been described in rather generic terms) need to be discussed at this point, both in terms of their nature and quality and the institutional instruments through which they could be implemented. Placing these investments within programmatic lines that would aim at addressing and supporting the ecological, technological and social transition – and all three to the same extent and at the same time – is no simple matter. It certainly cannot be done by relying mostly on the market and competition, which, whenever they are extended to social goods – such as welfare – this inevitably leads to privatizing them.

Moreover, if there is little said about the public instruments through which the investments would be made, there is a risk of relying predominantly on private businesses, which would mean simply dropping funding on them from above, as if from a giant open tap. Why don’t we take a different path, and envision going beyond the existing Agencies and replicating the model of the large-scale “European public enterprise,” as was done with the Galileo project that brought so many benefits to both Europe and Italy? Why not think about the proposal for a “European public structure” put forward by Massimo Florio for the pharmaceutical industry, towards which the European Parliament has already shown favor, as something that could be implemented and extended to other sectors that are just as crucial and critical?

In the absence of such directions, both the Letta report and the Draghi report leave the impression that, beyond the praiseworthy idea of simplifying regulations and bureaucracy, their major focus goes no further than attempting to channel large amounts of private savings into investments. To this end, they offer questionable proposals, such as creating a private “third pillar” pension system for European citizens (instead of pushing them to invest the same resources in the public pension system, which is much safer, while its framework is in need of strengthening), or seeking a reduction in constraints and regulations, whose absence, however, would open up new spaces for an already extensive and pernicious financialization.

We cannot forget that financialization, exploiting the benevolence of regulators and the spaces opened up by privatization, has increased the complexity of financial markets – giving rise to an entire fauna of intermediaries and peculiar financial pyramids and transforming risk management into aggressive risk-taking – and has fueled the emphasis on the ownership of stocks and the creation of value through them, with the proliferation of stock options resulting in the guiding principle of economic activity becoming increasing shareholder value instead of production.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/lausterita-e-i-limiti-del-piano-draghi on 2024-10-09