Reportage

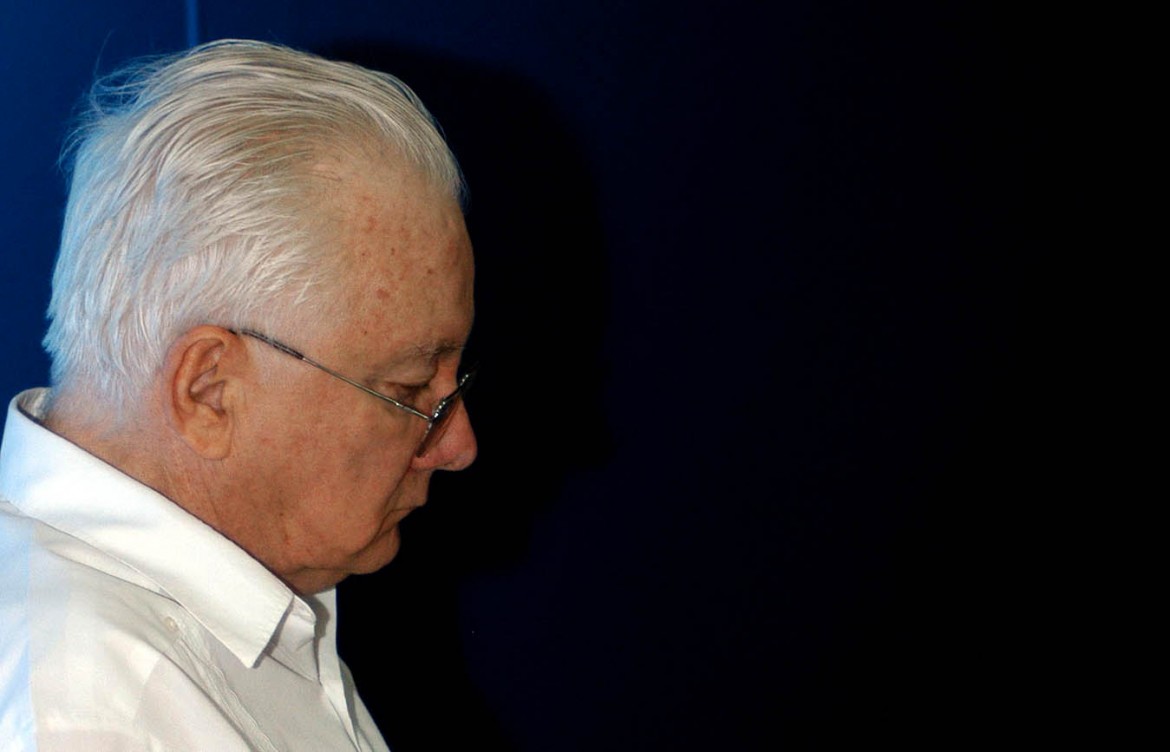

Armando Hart, minister of Cuban revolutionary culture, dies

Raúl Castro attended the farewell ceremony for Revolutionary Cuba’s first minister of education, who eradicated illiteracy on the island.

Some of the credit for the fact that socialist Cuba was able to survive the implosion of the USSR must go to Armando Hart, the intellectual and comrade-in-arms of Fidel Castro, who died last week at age 87.

He was the first Minister of Education of Fidel’s revolutionary government, who took on the task “to make the school the main cultural institution on the island.” Most importantly, it was Hart who, again following the command of the líder maximo, placed the thought of José Martí “at the center of the radiating core” of the politics, culture and ethics of the Cuban socialist model.

This component based on Martí’s thought, which envisions for the patria grande the political- and cultural-historical basis for the liberation of Latin America, is nowadays not only at the heart of Cuba’s politics, but also at the core of the “Socialism of the 21st Century” of the Bolivarian alliance with Venezuela, Bolivia and Ecuador in particular. No wonder that on Monday, Raúl Castro himself took part in the farewell ceremony at the headquarters of the José Martí Cultural Society, an institution established and run by Hart.

The Cuban president, who has repeatedly said he will renounce the office in February, has minimized his public appearances in recent months, letting Vice President Miguel Díaz-Canel, considered his most likely successor, take the spotlight. By his participation on Monday, Raúl, as the leader of Cuban politics and culture, has given Hart the highest honor.

Hart, who had recently needed to cut back on his activity due to health problems and was using a wheelchair, was a lawyer by formation. He was an active participant in the struggle of the opposition against the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, and began his association with Fidel Castro in 1955, during the establishment of the National Directorate of the 26th of July Movement, the political arm of the guerrillas.

“I can say confidently that my life can be divided into two stages: before and after I met Fidel,” he said a year ago while attending Castro’s funeral.

During the struggle for liberation, he met Haydée Santamaria, one of the heroines of the revolution and the founder of the cultural institution Casa de las Américas. She became his first wife. After the triumph of the revolution, he was appointed Minister of Education (1959-65), and was the promoter and organizer of the famous large-scale literacy campaign, involving millions of Cubans of all ages, which ended illiteracy on the island.

He was a member of the Political Bureau of the Cuban Communist Party until 1991, and established and led the Ministry of Culture in 1976, the year when he was also elected to the National Assembly. In 1977, he was charged by Fidel with starting the José Martí Cultural Society, to preserve the memory and work of the “Apostle of the Fatherland.”

With Marti’s thought and “Fidelist” principles as his platform, Hart dedicated the last years of his life to efforts to preserve the continuity of the Cuban revolutionary process. In essence, this was a dialogue between the different generations, an “exchange of experience between two centuries” — between those who made the revolution happen and took over political and administrative responsibility, and the new generations that will be tasked to preserve its continuity now, “at the beginning of the 21st century.”

“Hart was a key figure for the integration of Cuban intellectuals into the revolutionary process,” says the historian and analyst Enrique López Oliva. “A man of great culture, who did research on Marx but also on Martí, he holds the merit of giving a political-philosophical foundation to the revolutionary movement, combining Marxist thought with the Latin American nationalist component, Martí’s ‘Patria grande.’”

Hart developed this perspective in a series of books. In recent days, on the anniversary of the first anniversary of Castro’s death, his book Cuando me hice Fidelista (“When I Became a Fidelist”) was presented, a volume edited by his second wife, Eloísa Carrera, who is now engaged in an editorial project to collect “the original thought” of Armando Hart.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/e-morto-armando-hart-il-ministro-della-cultura-della-rivoluzione/ on 2017-12-03