Interview

Argentine ‘death flights’ no longer carry secrets

We spoke with Giancarlo Ceraudo, who spent years working on an investigation into death flights. “From a historical point of view, I have always had a passion for the Second World War, especially for the question of the Third Reich and Nazism.”

Giancarlo Ceraudo (born in Rome in 1969) is waiting for a phone call to leave for Cuba. But more likely, he will go to Barcelona to document the rallies post-referendum for Catalan independence. But on Oct. 27 and 28, he will be in Lodi for the 8th edition of the Festival of Ethical Photography, an exhibition organized by Alberto Prina and Aldo Mendichi with the Gruppo Fotografico Progetto Immagine (until Oct. 29), to present the book Destino Final (Schilt, 2017) together with Argentine journalist Miriam Lewin.

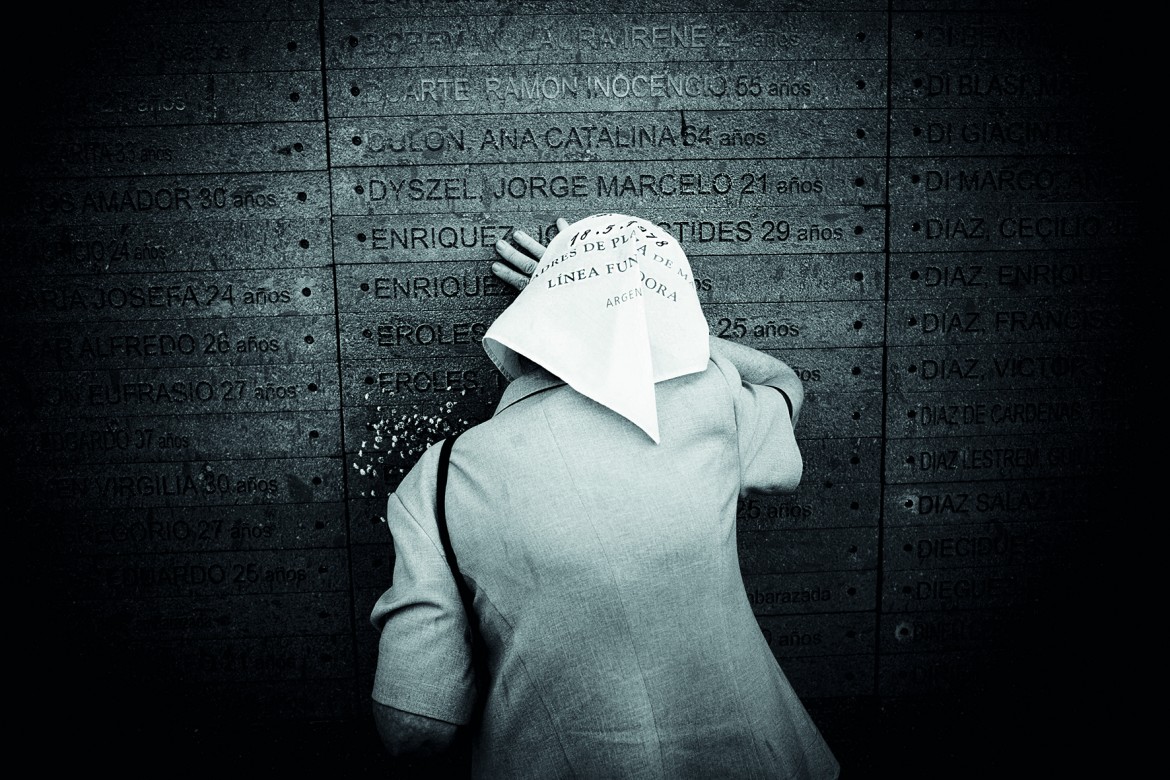

His photographic inquiry, the first on “death flights,” showcases a selection of images, all in black and white. “Color is cantankerous,” says the photographer. “It is less polite than black and white, which in this case gave me the timeless space I needed.”

The story began in 2002 and is still going, at least as far as the path of justice is concerned. At the photographic level, it ended with the publication of the book (curated by Arianna Rinaldo), with contributions by Miriam Lewin, journalist Horacio Verbitsky, judge Baltasar Garzón Real, former pilot Enrique Piñeyro (also a physician, actor, director and film producer) and anthropologist Carlos ‘Maco’ Somigliana.

The past was hidden until the Ceraudo-Lewin team’s research led to aircraft identification (including Skyvan PA-51, found in Fort Lauderdale, Florida) and flight plans, the ones carried out in the years 1976-1981, when the Argentine military junta made thousands of young opponents disappear, mostly students, loading them under sedation onto planes that dropped them alive into the Atlantic Ocean. Thousands of desaparecidos.

“The path of justice is not something that concerns me, but I respect it. I have my idea, and my line of reasoning is simple. Did the death flights happen? Yes. Did they do it with the planes? Yes. How many planes did they have? Five? Yes. How many pilots were involved? Twenty? Yes. Were any of these 20 pilots there, or not? Their names are listed on the flight plan sheets. Those 20 names. These are ideas that, rightly, must be proven, otherwise it would be a jumble.”

When a project goes on for 15 years, like Destino Final, does it limit your ability to do other projects?

No, I developed it in parallel to my photography career. Photography is something that tells contemporary stories. It is more dynamic. This project, which in some ways was also frustrating, is more like a painting. Not for the quality of the images, but for the times. It is a less professional work, in the sense that it has become a piece of life in which I put my relationships, my things. Even economically, to carry it forward I had to get rid of the logic of profit. But the beautiful thing was the involvement of people. Two-thirds of the project, the whole investigation part, was shared with Miriam. It is a collective work.

What were the biggest difficulties in telling this piece of history?

I often considered this work as the son of a lesser god, and then I accepted its aesthetic beauty as well. My photography is very aesthetic and even cinematic. I think a part of me has come into it that has nothing to do with photography.

Probably just because I was born in Rome — when I was a child, I used to look at the Colosseum thinking I would have liked to turn into a stone to live indefinitely and see people — I’m used to having a relationship with matter, which is something that has a soul.

Even architects say there are traces in the matter and these give directions that can lead to a hidden truth. The camera allowed me to do this reflection. If I had just fixedly looked at the matter, I would have seemed crazy, but photography gave me a justification to observe it.

And emotionally, what can you say about the project?

The appearance of my somewhat desecrating character allowed me to surf on this story, go around it, walk on it. These stories are far bigger than me, and if you start thinking about being the protagonist, taking them, dominating them and controlling them, you can not only fail, but you get hurt.

I learned a lot from people, especially from Miriam, who, despite being an investigative journalist, had nothing to do with dictatorship and its life before this story. She is a survivor. Photography was also a great drainage channel that made the history manageable.

What led you to investigate the “death flights”?

In 2001, I went to Argentina to see what was happening with the economic crisis. From a historical point of view, I have always had a passion for the Second World War, especially for the question of the Third Reich and Nazism. I found it absurd that, at one point, a whole people would participate in a genocide. They were normal people, because it’s not possible that everybody had a criminal mind, but they would still adhere to it, or, in any case, actually be part of it. Then I was 17, 18 years old.

Fifteen years later, perhaps because of the anthropology studies I never finished, I learned about the dictatorships in South America. I saw photos of characters that resembled Nazis a lot. There was also the story of the escape of Hitler’s henchmen to Argentina, so everything was linked. The idea, in particular, came to me when I watched the film Garage Olimpo (1999), which, beyond beauty, is one of the few films and even the most important about the Argentine dictatorship to have entered the common perception.

This film is also linked to my personal experience with aircraft. As a child, my father took me to the Urbe airport. For me the plane was the trip. My brother then wanted to be a pilot, and he had many models. In the movie, I was struck by the incident of death planes. Unlike anything I had studied in my youth, this was still alive. The protagonists themselves were still alive, so I thought I was in a slice of history where I could see something.

Absurdities happened during the course of the project. Things that seemed to be written in a script. Every time I got detached, there was something coming to me and reeling me back in that world.

Can you tell us something that happened to you during your work on Destino Final?

One of the anecdotes of this story is that in Garage Olimpo, there is a character I had in mind, “El Tigre” (Jorge Eduardo Acosta), head of the detention center from which death flights took place. In the last scene of the film, he puts inmates on the plane, played by Miriam. An actor I had also watched in Alambrado, the first film by Marco Bechis.

So then with the idea of looking for the airplanes, following my own aeronautical reasoning, I met Joe Goldman, ABC News reporter — he had been one of the few reporters who interviewed El Triga Acosta when he was still free — and I told him my goal. He told me that no one had ever thought about it and that I should have spoken with Piñeyro, who had been a pilot. Randomly, just the day before I had gone to watch the movie Whiskey Romeo Zulu (the name of a plane), where he also played a part. He was super famous, I did not think he would listen to me. Instead, when I called him, he was very calm.

When we met, he confirmed my assumptions. The key part was actually studying the flight plans along with Enrique. He was also very helpful when, after a while, with Carlos ‘Maco’ Somigliana and Miriam Lewin it was decided that the denunciation should be made by two important figures. One is Enrique Piñeyro, a well-known public figure, and the other is Pérez Esquivel, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/gli-aerei-senza-ritorno-non-hanno-piu-segreti/ on 2017-10-12