Reportage

After the Christian exodus from Iraq, Nineveh is no longer the same

The violence and persecution of ISIS has emptied the plain. As Pope Francis arrives, only a portion of the families who fled in 2014 as the jihadists advanced have returned. There are even some who dream of an autonomous ‘Christianistan.’

It was the summer of 2017 when Labib Rammo, his wife and six children became known throughout Iraq as the first family of the Christian faith to return to the town of Karamles. A return that, on the one hand, symbolized the defeat—at least on a military level—of Daesh (ISIS), which had sown death and destruction in the Nineveh Plain and surrounding territory, and on the other signaled a new beginning for the Chaldeans, one of the world’s oldest Christian communities and heir to the ancient Assyrian civilization.

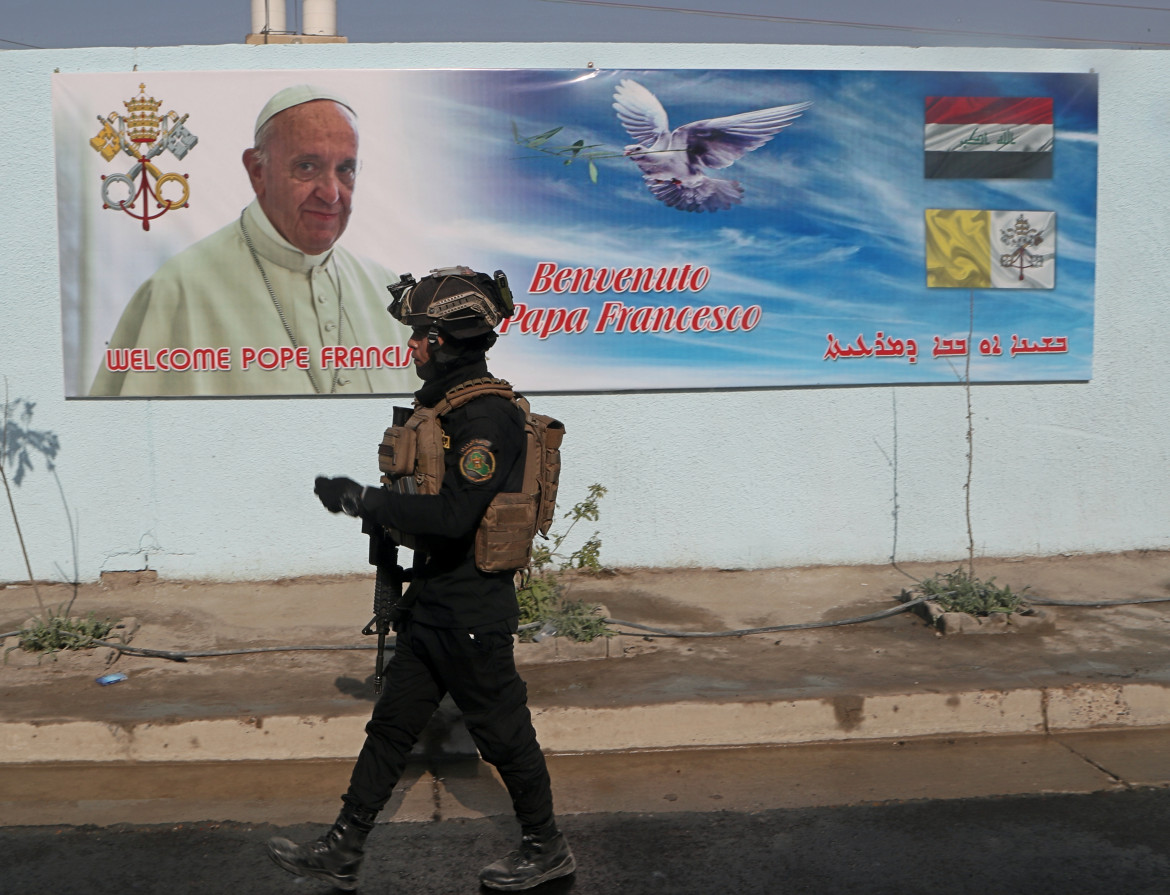

More than three years later, that hope has largely vanished. On his visit to Iraq, Pope Bergoglio will not only find an unstable country, bent under the weight of poverty, economic crisis, sectarian divisions and victim of important geopolitical interests. He will also encounter a fragile Christian community, undecided whether to stay or abandon the land where the roots of its ancient presence lie.

Father Thabet, the parish priest of Karamles, stayed as long as he could in 2014 as Daesh jihadists advanced on the town. Since returning there, he tells il manifesto, he has realized that his place will forever be in Karamles. But, he acknowledges, “it’s not easy, we are Iraqis, we experience the enormous problems of our people, and our daily life is made of continuous challenges and obstacles.”

So many of those who left the city never returned. “Only 345 of the 820 families who fled have returned,” Father Thabet continues. “The young people in particular are struggling to see their future in this city.” Security, he explains, remains an essential issue, “and in this economic situation it is difficult to make plans. It is not by chance that the most qualified and educated citizens are remaining far away (from Karamles).”

This picture is also corroborated by the inhabitants of the other centers of the Nineveh plain. Rebuilding after the destruction caused by jihadists and war has been the easiest part. Destroyed churches have been rebuilt with the help of the Vatican and international donations. Many houses have also been rebuilt—in Karamles, 60% of the civilian housing stock is back—but, as Father Thabet concludes, “the economic and social fabric remains frayed and we do not see any short-term solutions.”

In 1987, Christians in Iraq numbered 1.4 million, 8 percent of the population. Today they are just 1 percent. Already after the Anglo-American invasion of Iraq in 2003, the fall of Saddam Hussein and the beginning of Sunni jihadist terrorism against Shiites, Christians and other ethnic and religious communities—thousands of Chaldeans together with tens of thousands of Iraqi Muslims—took refuge in Syria and Jordan. Some of them returned to their homeland; but those who had the possibility chose to go to the U.S., Europe and other countries.

The most dramatic moment came after the historic speech in the mosque of Mosul by the “Caliph” Abu Bakr Al Baghdadi. ISIS militiamen took control of Sinjar and the Nineveh Plain, and on the night between August 6 and 7, at least 150,000 Christians fled in a hurry to Iraqi Kurdistan. An even more tragic fate befell other communities, and it is sadly well known what happened to Yazidi men and especially women. Then, in 2016, the Christian settlements—including Karamles and Qaraqosh—were liberated one by one by government troops, Shiite militias and Kurdish peshmerga.

Today, quite a few of the refugees who have returned home say they dream of the constitution of a sort of autonomous province for Christians and Yazidis in the Nineveh plain, defended by a local militia similar to the Shiite ones. A “Christianistan” that does not find the support of the Chaldean Patriarchate, which considers it a mistake from all points of view. This solution would also represent another failure for Iraq, already a sickly offspring of the ethnic-religious mosaic created in the Middle East by colonialism and the Anglo-French Sykes-Picot agreements for the partition of the Ottoman Empire.

Rifat Bader acts as the connection point between Iraqi Christians who have returned to their homes and those in Jordan. He explains that the suffering, the dramas of the last 30 years, from the first Gulf War to ISIS, have strengthened the faithful’s attachment to Christian institutions. “The visit of Pope Francis is highly anticipated, not only in the plain of Nineveh,” he tells us. “The Holy Father represents hope for Christians and all Iraqis affected by wars, conflicts, attacks and an economic crisis aggravated by the pandemic. Iraq and its people have a tremendous need to hear words of hope and compassion.”

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/lesodo-dei-cristiani-diraq-ninive-non-e-piu-la-stessa/ on 2021-03-05