Review

A voice against empire and its modern echo

‘Tomorrow They Won’t Dare to Murder Us’ by Joseph Andras reveals that empire’s cruelty never left us.

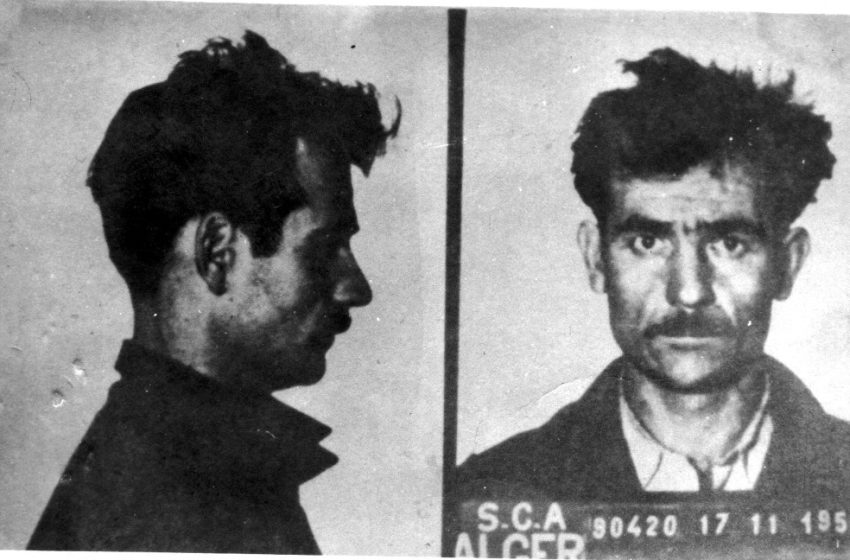

“There is no heart the state can constrain; dreams eat into its reason like acid.” These words arrive just before Fernand Iveton is executed in Joseph Andras’s blistering novel from 2015, De nos frères blessés (released in English by Verso in 2021 under the title Tomorrow They Won’t Dare to Murder Us). Fernand was a real man, a pied-noir (a Frenchman born in Algeria) who chose to fight with the Algerians for independence and was guillotined on February 11, 1957. The only French national to be executed during the Algerian War, his story was infamous in its time. Two years after he was killed, Sartre wrote a piece titled Nous sommes tous des assassins, condemning his execution.

Joseph Andras’ choice to revive and retell Fernand’s story was prescient. As Israel’s brutal invasion of Gaza is now well into its second year and Israeli troops continue to bomb and shoot innocent civilians, the logic of violence and the refusal of otherwise decent men to recognize it and stop it remains as relevant today as it was in the colonial era. It also gives us a map of how to navigate these dark times. Andras’s retelling focuses on a man who identified injustice and took principled action to fight it. Fernand remained staunchly committed to a better future, even as he faced the guillotine.

The novel begins as Fernand waits to receive the bomb from his FLN comrades. He’s planned to commit a violent political act without killing anyone, placing the bomb in a disused factory shed and timing it to explode after all the workers are gone. His goal with his attack is to prove that “not all European Algerians are anti-Arab.” He wanted his bomb, blunt instrument though it is, to be a symbol.

Taut and tense, a less focused novelist would make this the focus of their novel, or at least draw out this section’s suspense. However, Andras has Fernand receive the bomb, plant it, and get caught before it explodes by page 6. The narration whips from Fernand suffering brutal torture to his wife being brought into the station to Fernand’s comrades Djali and Jaqueline trying to dispose of a second bomb before Fernand cracks. As the suspense — and torture — ratchets up, the jumps speed up until external and internal dialogue, action and exposition interrupt each other, signifying the breaking of Fernand, his terrorist cell, and the legal system around him.

Inevitably, all goes awry. Fernand, after being burned, electrocuted, and waterboarded, breaks. The hunt begins for the comrades he named, and Fernand discovers that he’ll face a military court for his attempted attack. Still, given the nature of his attack, he’s told it’s unlikely he’ll be executed. Fernand dares to hope that France will respect the legal rights it claims it bestows upon all its citizens.

The remainder of the novel examines the machinery of empire, the praxis of resistance, and how Fernand met his wife, Hélène. The flashbacks to Fernand courting Hélène and meeting her family provide a relief from his current hell in a jail cell and show the humor, joy, and love he had in a previous life. They also serve to spell out his political growth and reasoning. He delivers a manifesto when Hélène comes to visit his grandfather:

Millions were born in [Algeria], and a handful of property-owners, barons who possess neither laws nor morals, have reigned over the country with the assent and even the backing of successive French governments: we must get rid of this system, clear Algeria of these kinglets and create a new regime with a popular base, made up of Arab and European workers together, humble people, the small and the unassuming of every race united to defeat the crooks who oppress us and hold us to ransom.

This passionate speech is greeted with chuckles and eyerolls by his grandfather, who pleads with her to forgive all his hot air.

When the trial begins, little of the facts are contested. Fernand set a bomb that never exploded. He set it in a place that ensured no one would have died. The only open debate is how to situate Fernand into France’s politics and its history. The French Communist party refuses to send legal aid because they think he’ll damage their reputation — he’s too similar to 19th century anarchist Auguste Vaillant. The narrator tells us that Fernand’s shoulders “are not broad enough to take on the mantle of the prefect of Eure-et-Loir, Jean Moulin,” hero of the French Resistance. Fernand’s stepson hopes that the goodwill earned by the pied-noir army hero Louis Franchet d’Espèrey might transfer onto his stepfather. Fernand argues for his own case eloquently: “For our group, it was never a matter of destruction or of making an attempt on anyone’s life. We were determined to draw the French government’s attention to the growing number of combatants fighting for greater social happiness in this land of Algeria.”

The French press, however, both in the novel and real life, vilified Fernand. “The French population in Algeria now knows who the monsters are and where they lurk. They’re talking about you, about communists, not very nice is it…” says one guard, gleefully reading the headlines.

This hints at Andras’s true motives, choosing to re-elevate Fernand Iveton from relative obscurity. A man condemned as a traitor held himself more true to the ideals of France than the French government ever did. For this, he was falsely called a murderer and put to death.

Tomorrow They Won’t Dare to Murder Us is as much a novel about the French colonial apparatus and how it sustained an unjust war in secret as it is a story about Fernand. Throughout the book, Andras is bracingly honest about what he sees is the problem. For years, France refused to admit there even was a war. “Power minds its language—its fatigues tailored from satin, its butchery smothered with propriety.”

Every ostensibly professional or decent-minded Frenchman is shown to be entirely ineffectual, either via incompetence or malevolence. Paul Teitgen, the earnest police reformer who arrived from Paris to put an end to torture in Algiers, is explained by a duty officer thusly: “He had brought his dainty ways along in his little suitcase, you should’ve seen, duty, probity, righteousness, ethics even—ethics my ass, he knows nothing about this place, nothing at all, do what you have to do with Iveton and I’ll cover for you… You can’t fight a war with principles and boy-scout sermons.”

The medical examiner that looked at Fernand after he claimed he was tortured submitted the following report: “the accused has ‘superficial scars on his torso and his limbs’ but, due to their age, ‘the exact cause of these marks is impossible to ascertain.’”

Here’s how Rene Coty, presented as the morally upright President of the Republic, responds to allegations of torture: “It is indeed unworthy of the police or army of the Republic to have behaved in such a fashion, should the alleged acts be confirmed.”

This willing ignorance, this obvious dissimulation in the face of evidence and facts is the lubrication that allows the gears of empire to grind down its subjects. If this sounds unfair or farfetched, we can see an even more malicious variant of this idea in Netanyahu’s spurious claims that civilian casualties were “practically none” when Israel invaded Rafah, that Israel is allowing plenty of food into Gaza, or that he was negotiating with Hamas in good faith.

The French media vilified Fernand, and being one man, Fernand was never able to correct the record. Andras takes up this work with his hardboiled, philosophical, terse, and humane 137-page book. When the gears of empire break people, Andras makes us hear their screams. He forces colonial powers to recognize the violence they meted out, the oppression they inflicted, and the sheer imbalance of power that they wielded. As Fernand explains to Hélène, “Death is one thing, but humiliation goes deeper, gets under the skin, it plants little seeds of anger and screws up entire generations.”

Andras, like Fernand, has created a potent symbol. But will it be enough to help us finally see through empires’ lies?

Originally published at on