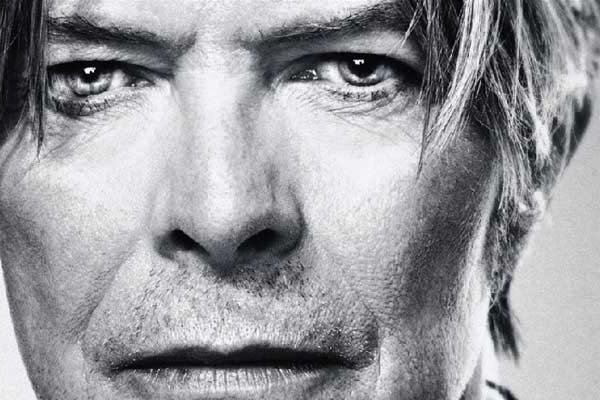

There isn’t just one Bowie, but a thousand Bowies to mourn. There is the glam Bowie of Ziggy Stardust or Diamond Dogs, the disco Bowie of Young Americans and Station to Station, the ice age of the infamous Berlin trilogy (Low, “Heroes”, Lodger), the dancing Bowie of Let’s Dance or Tonight. His genius was his uncontrollably changing self-representation, constantly cannibalizing itself to create new turmoil, insight and vision.

That game went on for years, until the dawn of the millennium and the great artistic crash. Bowie — who had already struggled through the ‘90s to find his place in the shifting artistic currents — almost left the scene. For a musician, timing is crucial. Like the Rolling Stones, who unveiled African-American blues to white audiences, or The Beatles, who showed love for soul and girl-group sounds — turning both bands into producers of culture — so Bowie was always in the right place at the right time.

It was Bowie who revealed — in a revolutionary way — that divisions of sex and gender weren’t so significant. He helped bring Lou Reed (as a producer on “Walk on the Wild Side” and the album Transformer) and Iggy Pop (“China Girl,” “The Passenger”) to mass popularity. Bowie has always embodied the mystical Berlin. He promoted Lindsay Kemp and Klaus Nomi. In 1975 he was the first to plug Kraftwerk, which launched the new romantics movement and became that rare icon appreciated even by the punk scene. Bowie wove film, fashion and art into his life. Bowie knew everything: what songs to dance to and what synthetic drug to use. He revealed to us the power of Mick Ronson, Earl Slick and Carlos Alomar, providing different perspectives on guitarists like Robert Fripp and Adrian Belew. Siloed, we knew very little. But we had Bowie, in the center of everything.

When the Bowie machine left this world, it took place amid a historic transition he expected but could not stop: the rise of the network. Now everyone, everywhere, at all times has become a little Bowie, at the center — or almost — of everything. The artist folds in on himself and loses the catalyst aura, which for years had characterized Bowie.

While the Rolling Stones or The Ramones have invested in a specific artistic identity largely unchanged over time, making them equally immortal, Bowie went the opposite direction. Certainly — proudly, beautifully — he is penalized for it. He admitted this himself in 2002, when he declared that music would soon become like running water or electricity. One year later, Apple released the iPod, confirming that decades or centuries of music could be lodged inside a small device. But Bowie’s prediction had gone a step further, that music would spring directly from the network. Six years later: Spotify.

In combatting the future, Bowie’s final strike was to predict his own artistic weakening. He stepped into the shadows, which to him was the abyss. What he’d already accomplished, however, has changed the lives of entire generations.

In 1974, he released the single “Rebel Rebel,” and it was another epochal event. He sang: “You’ve got your mother in a whirl. She’s not sure if you’re a boy or a girl.” Even this was a first for rock: himself, the characteristically androgynous artist, in a song blending identity and gender, merging images through which male and female adolescents — as sociologist Dick Bebdige pointed out years ago — transition from childhood to maturity and therefore the world of work. Culturally, it had enormous sexual and social implications.

Bowie therefore appeared the perfect antidote to the older generation. It had already happened with rock ‘n’ roll in which adverbs like “forever” abounded in songs, suggesting the desires of adolescents. But this time sex was in the open — and 1974 is not 2016. Even though in recent years Bowie was not very prolific (partly for health reasons), it was still important to know he was still working, recording his mutations and imaginings. He still is with Blackstar. And no can ever take it away, not even his last joke, the most brutal.