Review

A philosophical disappearance

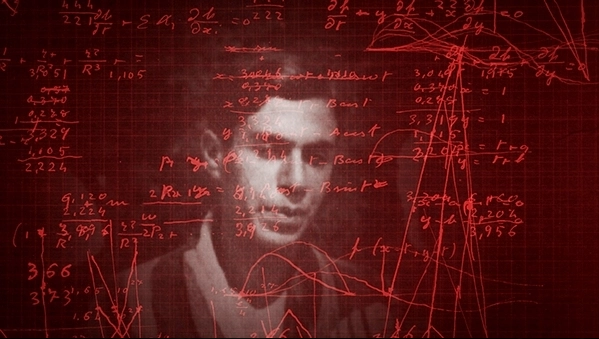

In his book, “What is real?” the philosopher Giorgio Agamben proposes a new theory on the disappearance of a famous Italian physicist: that the whole thing was an experiment in quantum physics.

On March 25, 1938, before embarking for Naples from Palermo, the famous physicist Ettore Majorana wrote a letter to his colleague Antonio Carrelli, referring cryptically to an “inevitable decision” related to his “sudden disappearance.” In another letter to the family, he asked them to limit their mourning to “not more than three days.” They sounded like the words from a suicidal person (except that he carried his passport and had withdrawn all his money).

The next day, 79 years ago this week, Majorana sent his last dispatch. He wrote again to Carrelli from Palermo: “The sea has refused me.” He also announced he would return to Naples. When Majorana had announced his intention to disappear, he resurfaced. Then he said he would return and instead he disappeared. Since then, many have asked about his letters: Were these the doubts of an undecided suicide or a perfectly concocted escape?

In 1975, the writer Leonardo Sciascia published an inquiry on Majorana that raised interest in the case. He identified possible theories: an escape to join the Nazis, a mysterious crisis, depression, a desertion from science to take up arms. The noteworthy theories can be counted on one hand because the scarcity of clues scare professional historians away. Aside from Sciascia, it’s been mostly physicists who have dealt with Majorana’s disappearance. Not even Giorgio Agamben is a historian; he teaches philosophy in universities across the world.

The most recent theory on Majorana’s disappearance is contained in Agamben’s latest book, Che cos’è reale? La scomparsa di Majorana (“What is real? The disappearance of Majorana”). In truth, Agamben does not propose an original historical reconstruction. Rather, he focuses on the reasons that led the physicist to disappear. According to Agamben, his disappearance was a kind of philosophical protest against quantum mechanics, the field in which Majorana excelled.

The physicist would have understood the consequences of indeterminism inherent in quantum theory. Unlike Newton’s laws taught in school, the theory developed by Bohr, Planck, Einstein and their colleagues in the early 20th century says it is impossible to predict where a particle is at any given time. At most, one can predict the probability that the particle is found at a given point. Furthermore, by measuring the position, you lose the opportunity to know precisely other measures that characterize the motion of the particle, known as the Heisenberg uncertainty.

The uncertainty associated with every empirical fact was not, in itself, a new concept: all measuring instruments, no matter how refined, have limited accuracy. But this does not contradict the deterministic view of reality: the uncertainty in the knowledge of the physical phenomena, which is manifested by a limited statistical variability, was shrinking all the time thanks to improved technologies.

Quantum mechanics, rather, gives uncertainty a new role: The particles were no longer represented as localized points, but as a “probability waves.” The scientist’s work was not to restrict the statistical uncertainty of the measurements in the experiments, but to predict how the waves change over time. The probability, which in classical physics measured the precision of the instruments, became itself the object of investigation at the deepest level.

Physicists had come to this conclusion on the basis of experimental observations unexplained in traditional terms, in which a single particle could be simultaneously in multiple states. Some theories were released at the time, for instance the example of “Schroedinger’s cat”: a thought experiment in which, following quantum principles, a cat is alive and dead at the same time. The paradox aimed to show that the oddities of quantum mechanics do not belong only to the microscopic world of particles, substantially inaccessible outside the laboratory: They are also seen in more complex systems with which we deal on a daily basis.

According to Agamben, Majorana designed his own death to show that the mental experiment can really be carried out: If he were a quantum particle, between March 25 and 26, 1938, Majorana disappeared and reappeared in different places simultaneously. He was alive and dead at the same time, like Schroedinger’s cat. Any attempt to reduce the uncertainty about the case is bound to fail. This is the unknowable world that the new physics offers to us; this was Majorana’s conclusion, according to Agamben’s interpretation. And it is a world to be rejected entirely, even before one wonders about its military implications.

The hypothesis is based on an essay written by Majorana himself, a popular article printed posthumously entitled ”The value of statistical laws in the physical and social sciences,” which had also intrigued Sciascia. In that essay, Majorana defined the new physics for a layman audience: “the result of any measurement therefore seems rather to measure the state in which the system is brought during the experiment itself, which is not the unknown as it was before being disrupted.”

Agamben interprets it as the description of a genetic mutation occurred in science. The philosopher wrote: “Science no longer sought to know reality, but, like the statistics applied to the social sciences, it attempts only to intervene on it to govern it.”

Simone Weil, quoted often by Agamben, had addressed a similar criticism of quantum theory. The transition from classical physics to quantum physics, according to Weil, was not justified by empirical evidence: “It is clear that discontinuity was not brought by experience (…) but only by the use of the probability concept,” she wrote. According to Weil, “giving up need and determinism in the name of probability, quantum mechanics had purely and simply given science up,” adds Agamben. Moreover, “even Einstein, who made a decisive contribution to quantum theory, held his reservations until the last minute about his interpretation based only in probabilistic terms.”

Agamben’s thesis on Majorana is striking. Unfortunately, there is no historical evidence to support it. It is not true, for example, that the adoption of quantum mechanics is disconnected from experience. The early development of the theory was motivated by abnormalities detected experimentally in the spectrum of light emitted by hot objects and the photoelectric effect and were not an immediate consequence of the probabilistic approach to physics. ”This extraordinary theory is therefore as solidly founded in experience as any other,” Majorana himself wrote in a passage not quoted by Agamben.

The strongest rebuttal to the completeness of quantum theory was published by Einstein in 1935. If Agamben was right, Majorana would have been particularly interested in it. Instead, over the course notes on the foundations of quantum theory held at the University of Naples in 1938, there is no trace of Einstein’s criticism.

The philosophical story of Majorana’s disappearance, therefore, does not reveal specific mysteries. Che cos’è reale? is instead a philosophical dissertation on the impact of quantum mechanics, in which the story of the missing writer only provides a little narrative spice.

Seventy-nine years after his disappearance, we continue to ignore almost everything. From a judicial perspective, it seems the story ended in South America with the identification of Majorana as a “Mr. Bini” photographed in Venezuela in the 1950s, but the “evidence” that supports this theory is laughable. Another famous photo purports to show him on the steamer fleeing to Argentina along with Nazi leaders. Again, efforts to identify him based on photographic comparisons are unsatisfactory.

The most reliable results are probably those obtained by physicists Francesco Guerra and Nadia Robotti, who, based on primary sources (including police reports and family correspondence) established that Majorana remained alive after his disappearance and died in 1939. In that year, his family established a scholarship in his name, and the police suddenly stopped searching. The Majorana case, perhaps, had already been solved.

Originally published at https://ilmanifesto.it/una-sparizione-filosofica/ on 2017-03-26